air being 59° of Fahrenheit, and that of the water 55°. The water waa

perfectly smooth, with an oily aspect from the surface, being covered with a

substance which was supposed to be the excrement of whales, of which

large numbers of various kinds, as well as of porpoises, were seen. At

daylight, on the 16th, the course was shaped at an angle approaching the

coast, and although the land had been for awhile out of sight, it was now

again made, and traced along until the ships reached the northeastern

extremity of Nippon, called. by the Japanese Sirija Saki. The southern

and eastern coast of Japan from Cape Sirofama, as far as was observed,

is not so high as that on the western side of the G-ulf of Yedo. I t is,

however, of sufficient height to be observed, in tolerably clear weather, at

a distance of forty miles. On getting abreast of Cape Sirija Saki, the

Strait of Sangar, which separates Nippon from Yesso, was full in view, with

the high land of the latter island distinctly visible ahead. The course was now

steered directly for Hakodadi, but on getting into the middle of the strait

a current or tide was encountered, which probably accelerated the eastern

one, until the two reached a combined velocity of six knots. This powerful

current prevented the steamers from reaching port that night, and it

was thought advisable to put the heads of the steamers seaward. This

would not have been necessary if any reliance could have been placed upon

the continuance of clear weather. The engines were so managed as to

expend little coal, and still to retain the position of the vessels; consequently,

on taking the cross-bearings at daylight, it was found, notwithstanding

the current, that the ships had not shifted their places a mile from where

they had been when night set in.

- Scarcely, however, had the steamers stood again for their destined port

when a dense fog came on and obscured every object from sight, so that it

was found necessary to head the steamers towards the east. The sun, however,

on approaching the zenith, cleared away the fog, and fortunately bearings

were distinguished which served as a guide to the port. As the cape, called

by the Japanese Surro-kubo, and which the Commodore named Cape Blunt,

in honor of his friends Edmund and George Blunt, of New York, was

approached, there could be discerned over the neck of land which connects

the promontory of Treaty Point * with the interior, the three ships of the

squadron which had been previously dispatched, safely at anchor in the

harbor of Hakodadi. At the approach of the steamers, in obedience to the

previous instructions of the Commodore, boats came off from the ships with

offioers prepared to pilot in the Powhatan and Mississippi, which finally came

to anchor at nine o’clock on the morning of the 17th of May.

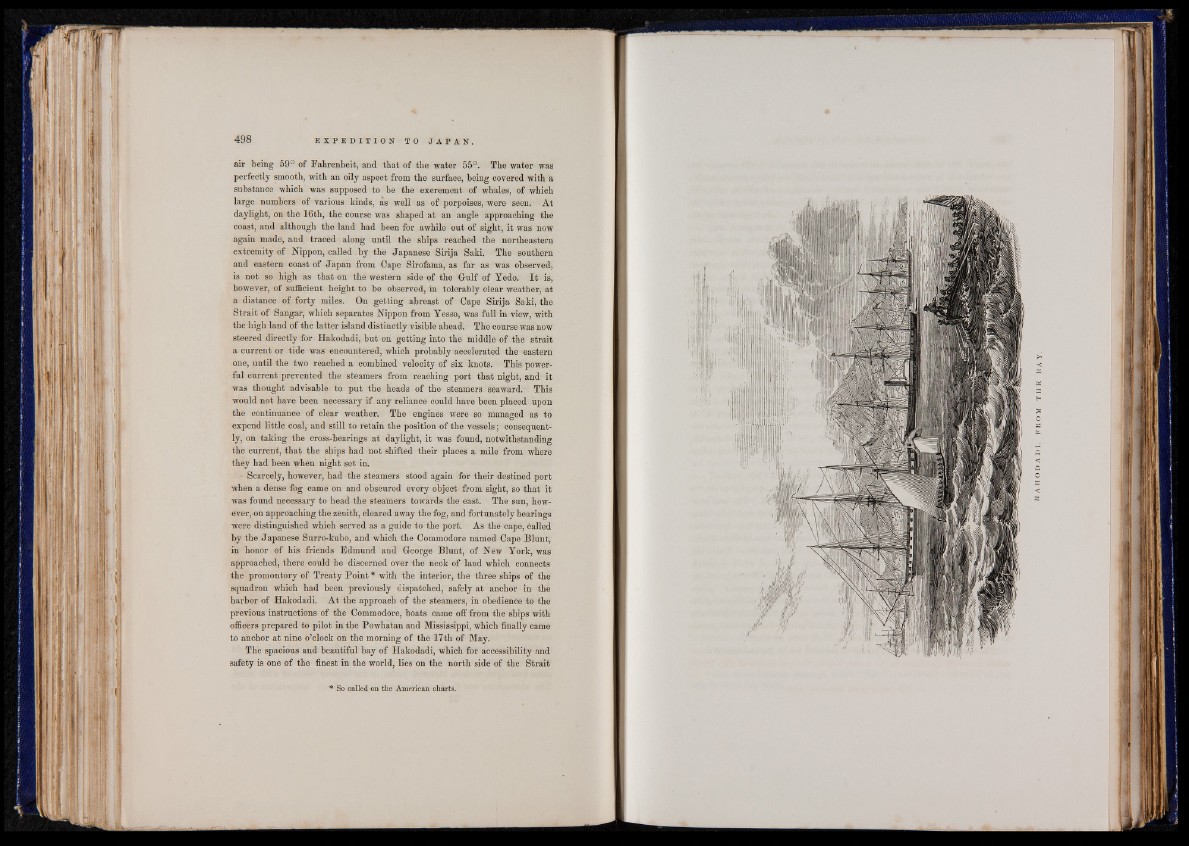

The spacious and beautiful bay of Hakodadi, which for accessibility and

safety is one of the finest in the world, lies on the north side of the Strait

* So called on the American charts.