It! IP

y

R i W) ml

i t s ™

PHI

II

1 1

\ \

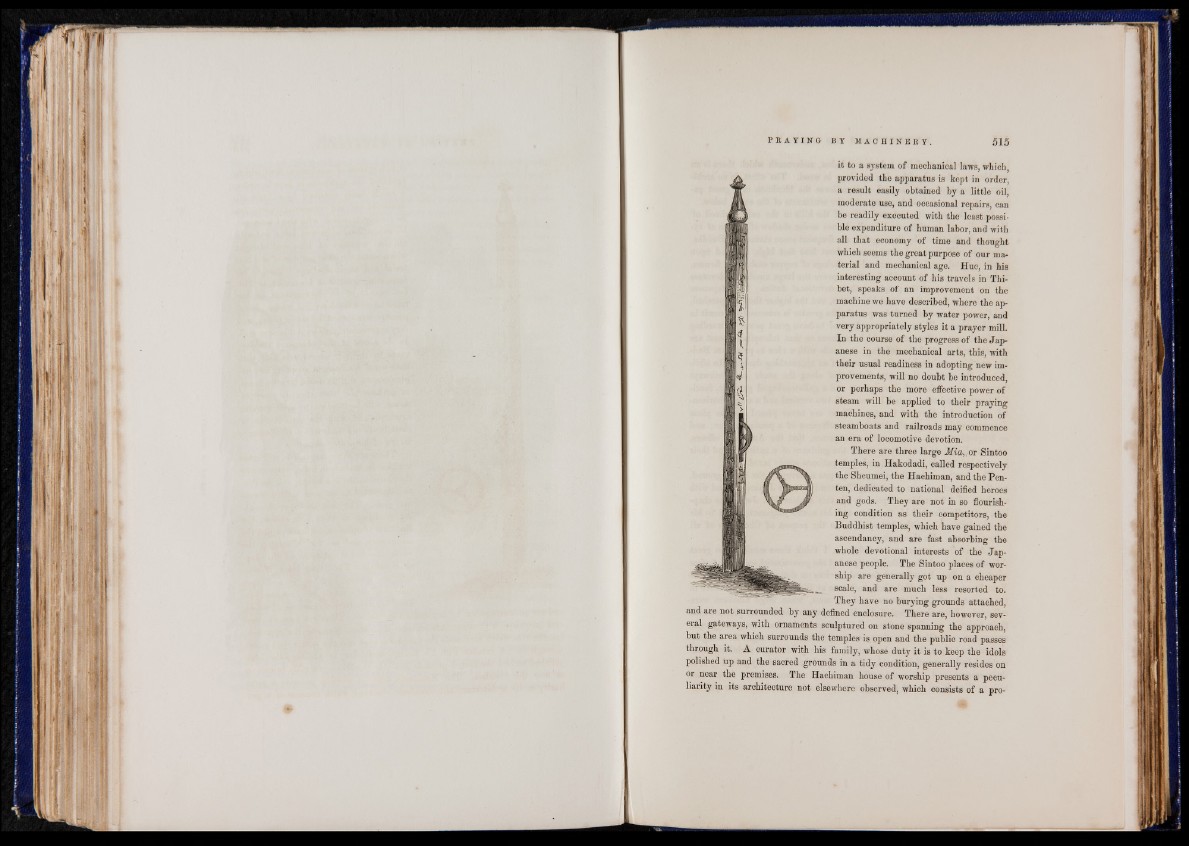

it to a system of mechanical laws, which

provided the apparatus is kept in order,

a result easily obtained by a little oil,

moderate use, and occasional repairs, can

be readily executed with the least possible

expenditure of human labor, and with

all that economy of time and thought

which seems the great purpose of our ma-

terial and mechanical age. Hue, in his

interesting account of his travels in Thibet,

speaks of an improvement on the

machine we have described, where the apparatus

was turned by water power, and

very appropriately styles it a prayer mill.

In the course of the progress of the Japanese

in the mechanical arts, this, with

their usual readiness in adopting new improvements,

will no doubt be introduced,

or perhaps the more effective power of

steam will be applied to their praying

machines, and with the introduction of

steamboats and railroads may commence

an era of locomotive devotion.

There are three large Mia,,or Sintoo

temples, in Hakodadi, called respectively

the Sheumei, the Hachiman, and the Pen-

ten, dedicated to national deified heroes

and gods. They are not in so flourishing

condition as their competitors, the

Buddhist temples, which have gained the

ascendancy, and are fast absorbing the

whole devotional interests of the Japanese

people. The Sintoo places of worship

are generally got up on a cheaper

scale, and are much less resorted to.

They have no burying grounds attached,

and are not surrounded by any defined enclosure. There are, however, several

gateways, with ornaments sculptured on stone spanning the approach,

but the area which surrounds the temples is open and the public road passes

through it. A curator with his family, whose duty it is to keep the idols

polished up and the sacred grounds in a tidy condition, generally resides on

or near the premises. The Hachiman house of worship presents a peculiarity

in its architecture not elsewhere observed, which consists of a pro