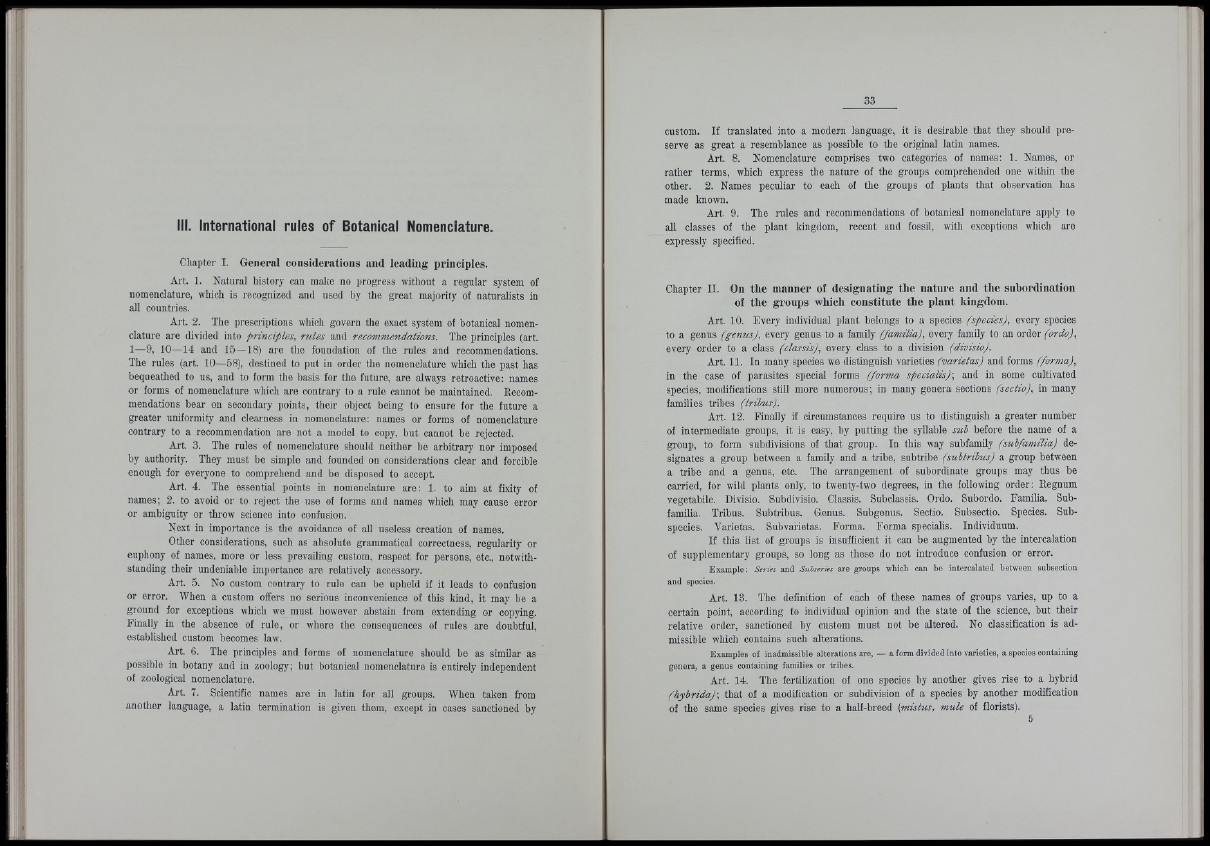

. International rules of Botanical Nomenclature.

Chapter I. General co n s id e ra tio n s an d le a d in g princ iples.

Art. 1. Natural history can make no progress without a regular system of

nomenclature, which is recognized and used by the great majority of naturalists in

all countries.

Art. 2. The prescriptions which govern the exact system of botanical nomenclature

are divided into principles, rules and recommendations. The principles (art.

1—9, 10—14 and 15 — 18) are the foundation of the rules and recommendations.

The rules (art. 10—58), destined to put in order the nomenclature which the past has

bequeathed to us, and to form the basis for the future, are always retroactive: names

or forms of nomenclature which are contrary to a rule cannot be maintained. Recommendations

bear on secondary points, their object being to ensure for the future a

greater uniformity and clearness in nomenclature: names or forms of nomenclature

contrary to a recommendation are not a model to copy, but cannot be rejected.

Art. 3. The rules of nomenclature should neither be arbitrary nor imposed

by authority. They must be simple and founded on considerations clear and forcible

enough for everyone to comprehend and be disposed to accept.

Art. 4. The essential points in nomenclature are: 1. to aim at fixity of

names; 2. to avoid or to reject the use of forms and names which may cause error

or ambiguity or throw science into confusion.

Next in importance is the avoidance of all useless creation of names.

Other considerations, such as absolute grammatical correctness, regularity or

euphony of names, more or less prevailing custom, respect for persons, etc., notwithstanding

their undeniable importance are relatively accessory.

Art. 5. No custom contrary to rule can be upheld if it leads to confusion

or error. When a custom offers no serious inconvenience of this kind, it may be a

ground for exceptions which we must however abstain from extending or copying.

Finally in the absence of rule, or where the consequences of rules are doubtful,

established custom becomes law.

Art. 6. The principles and forms of nomenclature should be as similar as

possible in botany and in zoology; but botanical nomenclature is entirely independent

of zoological nomenclature.

Art. 7. Scientific names are in latin for all groups. When taken from

another language, a latin termination is given them, except in cases sanctioned by

custom. If translated into a modern language, it is desirable that they should preserve

as great a resemblance as possible to the original latin names.

Art. 8. Nomenclature comprises two categories of names: 1. Names, or

rather terms, which express the nature of the groups comprehended one within the

other. 2. Names peculiar to each of the groups of plants that observation has

made known.

Art. 9. The rules and recommendations of botanical nomenclature apply to

all classes of the plant kingdom, recent and fossil, with exceptions which are

expressly specified.

Chapter II. On th e m a n n e r of d e s ig n a tin g th e n a tu re an d th e su b o rd in a tio n

of th e g ro u p s which c o n s titu te th e p la n t kingdom.

Art. 10. Every individual plant belongs to a species (species), every species

to a genus (genus), every genus to a family (familia), every family to an order (ordo),

every order to a class (classis), every class to a division (divisio).

Art. 11. In many species we distinguish varieties (varietas) and forms (forma),

in the case of parasites special forms (forma specialis)', and in some cultivated

species, modifications still more numerous; in many genera sections (sectio), in many

families tribes (trihus).

Art. 12. Finally if circumstances require us to distinguish a greater number

of intermediate groups, it is easy, by putting the syllable sub before the name of a

group, to form subdivisions of that group. In this way subfamily (subfamilia) designates

a group between a family and a tribe, subtribe (subtribus) a group between

a tribe and a genus, etc. The arrangement of subordinate groups may thus be

carried, for wild plants only, to twenty-two degrees, in the following order: Regnum

vegetabile. Divisio. Subdivisio. Classis. Subclassis. Ordo. Subordo. Familia. Subfamilia.

Tribus. Subtribus. Genus. Subgenus. Sectio. Subsectio. Species. Subspecies.

Varietas. Subvarietas. Forma. Forma specialis. Individuum.

If this list of groups is insufficient it can be augmented by the intercalation

of supplementary groups, so long as these do not introduce confusion or error.

Example: Series and Subseries are groups whicli can be intercalated between subsection

and species.

Art. 13. The definition of each of these names of groups varies, up to a

certain point, according to individual opinion and the state of the science, but their

relative order, sanctioned by custom must not be altered. No classification is admissible

which contains such alterations.

Examples of inadmissible alterations are, — a form divided into varieties, a species containing

genera, a genus containing families or tribes.

Art. 14. The fertilization of one species by another gives rise to a hybrid

(hybrida)', that of a modification or subdivision of a species by another modification

of the same species gives rise to a half-breed (mistus, mule of florists).

> i l\