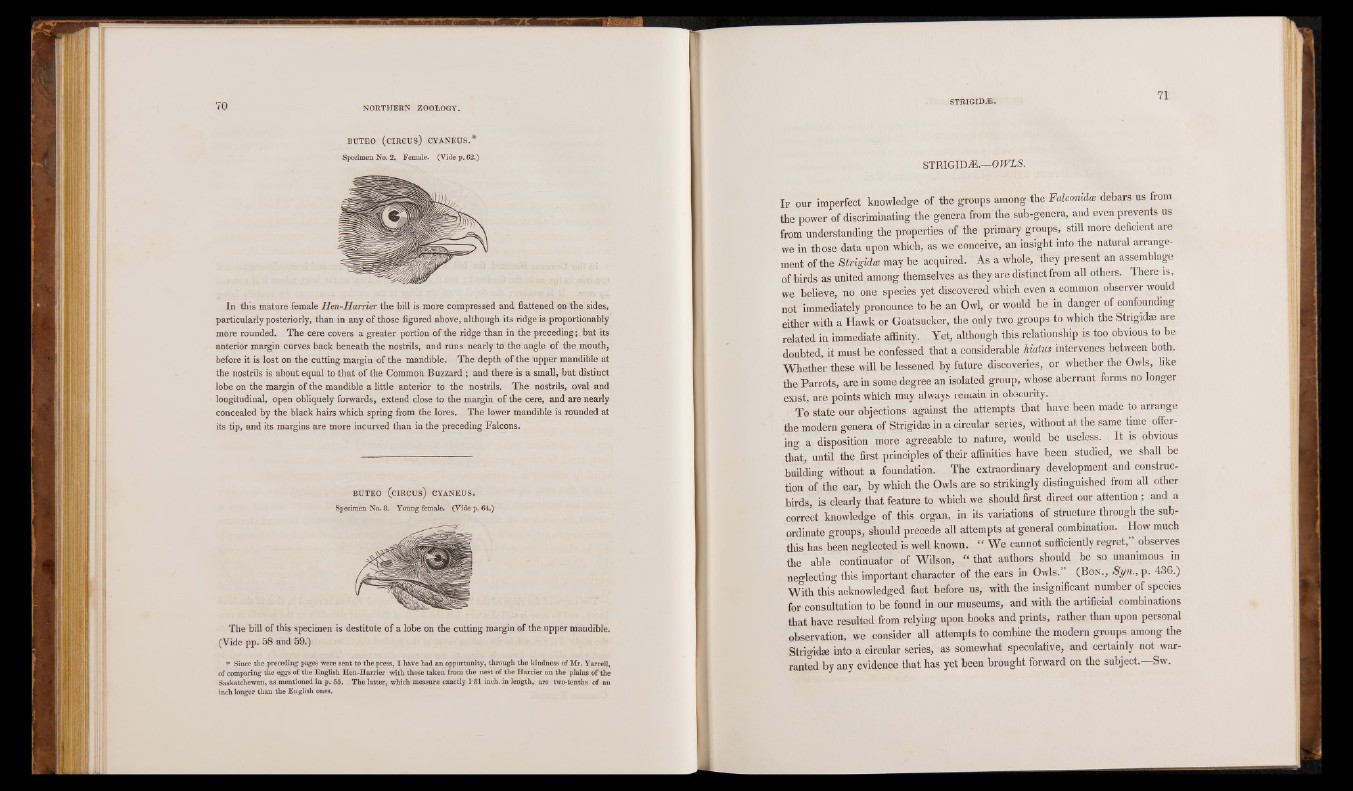

BUTEO (CIRCUS) CYAN1US.*

Specimen No. 2. Female. (Vide p. 62.)

In this mature female Hen-Harrier the bill is more compressed and flattened on the sides,

particularly posteriorly, than in any of those figured above, although its ridge is proportionably

more rounded. The cere covers a greater portion of the ridge than in the preceding; but its

anterior margin curves back beneath the nostrils, and runs nearly to the angle of the mouth,

before it is lost on the cutting margin of the mandible. The depth of the upper mandible at

the nostrils is about equal to that of the Common Buzzard ; and there is a small, but distinct

lobe on the margin of the mandible a little anterior to the nostrils. The nostrils, oval and

longitudinal, open obliquely forwards, extend close to the margin of the cere, and are nearly

concealed by the black hairs which spring from the lores. The lower mandible is rounded at

its tip, and its margins are more incurved than in the preceding Falcons.

BUTEO (c ir c u s ) CYANEUS.

Specimen No. 8. Young female. (Vide p. 64.)

The bill of this specimen is destitute of a lobe on the cutting margin of the upper mandible.

(Vide pp. 58 and 59.)

* Since the preceding pages were sent to the press, I have had an opportunity, through the kindness of Mr. Yarrell,

of comparing the eggs of the English Hen-Harrier with those taken from the nest of the Harrier on the plains of the

Saskatchewan, as mentioned in p. 65. The latter, which measure exactly 1*81 inch, in length, are two-tenths of an

inch longer than the English ones.

STRIGID.®.—OWLS.

If our imperfect knowledge of the groups among the Falconidte debars us from

the power of discriminating the genera from the sub-genera, and even prevents us

from understanding the properties of the primary groups, still more deficient are

we in those data upon which, as we conceive, an insight into the natural arrangement

of the Strigida may be acquired. As a whole, they present an assemblage

of birds as united among themselves as they are distinct from all others. There is,

we believe, no one species yet discovered which even a common observer would

not immediately pronounce to be an Owl, or would be in danger of confounding

either with a Hawk or Goatsucker, the only two groups to which the Strigid® are

related in immediate affinity. Yet, although this relationship is too obvious to be

doubted, it must be confessed that a considerable hiatus intervenes between both.

Whether these will be lessened by future discoveries, or whether the Owls, like

the Parrots, are in some degree an isolated group, whose aberrant forms no longer

exist, are points which may always remain in obscurity.

To state our objections against the attempts that have been made to arrange

the modern genera of Strigid® in a circular series, without at the same time offering

a disposition more agreeable to nature, would be useless. It is obvious

that, until the first principles of their affinities have been studied, we shall be

building without a foundation. The extraordinary development and construction

of the ear, by which the Owls are so strikingly distinguished from all other

birds, is clearly that feature to which we should first direct our attention; and a

correct knowledge of this organ, in its variations of structure through the subordinate

groups, should precede all attempts at general combination. How much

this has been neglected is well known. “ We cannot sufficiently regret, observes

the able continuator of Wilson, « that authors should be so unanimous in

neglecting this important character of the ears in Owls. (Bon., Syn., p. 436.)

With this acknowledged fact before us, with the insignificant number of species

for consultation to be found in our museums, and with the artificial combinations

that have resulted from relying upon books and prints, rather than upon personal

observation, we consider all attempts to combine the modern groups among the

Strigid® into a circular series, as somewhat speculative, and certainly not warranted

by any evidence that has yet been brought forward on the subject.—Sw.