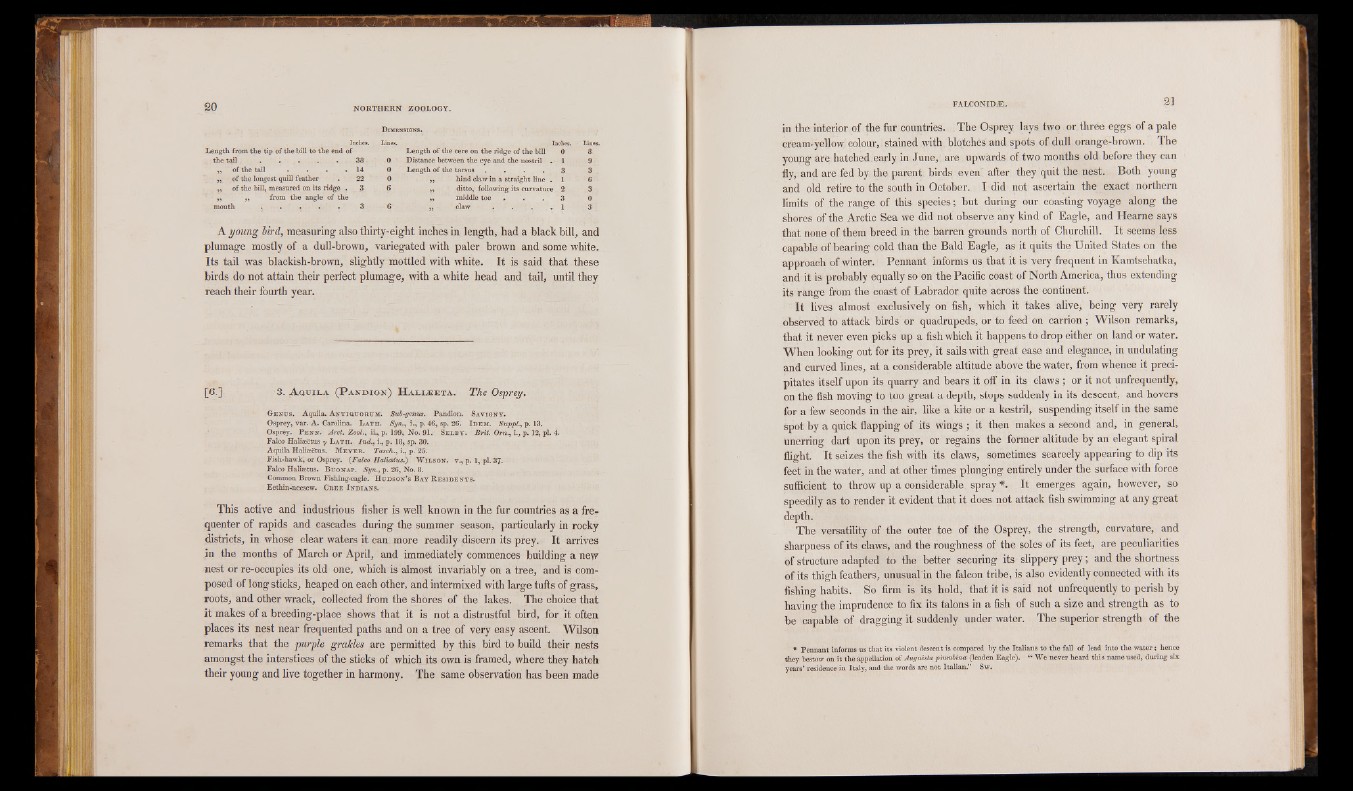

Dimensions.

Length, from the tip of the bill to the end of

Inches. lines. the tail. . . . . 38 0

„ ’ of the tail 14 0

„ of the longest quill feather 22 0

,, of the bill, measured on its ridge . 3 6

„ „ from the angle

of the

mouth . . . .

3 6

- Inches. - Lines.

Length of the cere on the ridge of the bill 0 8

Distance between the eye and the nostril . • 1 9

Length of the tarsus . . . . 3 3

- „ hind daw in a straight line . 1 6

„ ditto,’ following its curvature 2 3

„ middle toe , 3 0

„ - daw . . . . 1 3

A young bird, measuring also thirty-eight inches in length, had a black bill, and

plumage mostly of a dull-brown, variegated with paler brown and some white.

Its tail was blackish-brown, slightly mottled with white. It is said that these

birds do not attain their perfect plumage, with a white head and tail, until they

reach their fourth year.

[6,] 3. Aquila (Pandion) Haiijeeta. The Osprey.

Ge n u s . Aquila. An t iq u o r u m . Sub-genus. Pandion. Sa v ig n y .

Osprey, var.-A. Carolina. Lath. Syn., i.,p. 46, sp. 26. I dem. Supply p. 13.

Osprey. P enn. Arct. Zool., ii., p. 199, No. 91. Selby. Brit. Ora., i., p. 12, pi. 4.

Falco Haliffietus y L a t h . Ind., i., p. 18, sp. 30.

Aquila Haliseetus. Meyer. Tasch., i., p. 25.

Fish-hawk, or Osprey. (Falco Haluetus.') Wilson, v., p. 1, pi. 37.

Falco Haliaetus. B u o n a p . Syn., p. 26, No. 8.

Common Brown Fishing-eagle. H u d so n ’s Bay R e s id e n t s .

Eethin-neesew. Cb.e e I n d ia n s .

This active and industrious fisher is well known in the fur countries as a frequenter

of rapids and cascades during the summer season, particularly in rocky

districts, in whose clear waters it can more readily discern its prey. It arrives

in the months of March or April, and immediately commences building a new

nest or re-occupies its old one, which is almost invariably on a tree, and is composed

of long sticks, heaped on each other, and intermixed with large tufts of grass,

roots, and other wrack, collected from the shores of the lakes. The choice that

it makes of a breeding-place shows that it is not a distrustful bird, for it often

places its nest near frequented paths and on a tree of very easy ascent. Wilson

remarks that the purple grakles are permitted by this bird to build their nests

amongst the interstices of the sticks of which its own is framed, where they hatch

their young and live together in harmony. The same observation has been made

in the interior of the fur countries. The Osprey lays two or three eggs of a pale

cream-yellow colour,^ stained with blotches and spots of dull orange-brown. The

young are hatched early in June,; are upwards of two months old before they can

fly, and are fed by the parent birds even after they quit the nest. Both young

and old retire to the south in October. I did not ascertain the exact northern

limits of the range of this species; but during our coasting voyage along the

shores of the Arctic Sea we did not observe any kind of Eagle, and Hearne says

that none of them breed in the barren grounds north of Churchill. It seems less

capable of bearing cold than the Bald Eagle, as it quits the United States on the

approach of winter. Pennant informs us that it is very frequent in Kamtschatka,

and it is probably equally so on the Pacific coast of North America, thus extending

its range from the coast of Labrador quite across the continent.

It lives almost exclusively on fish, which it takes alive, being very rarely

observed to attack birds or quadrupeds, or to feed on carrion; Wilson remarks,

that it never even picks up a fish which it happens to drop either on land or water.

When looking out for its prey, it sails with great ease and elegance, in undulating

and curved lines, at a considerable altitude above the water, from whence it precipitates

itself upon its quarry and bears it off in its claws ; or it not unfrequently,

on the fish moving to too great a depth, stops suddenly in its descent, and hovers

for a few seconds in the air, like a kite or a kestril, suspending itself in the same

Spot by a quick flapping of its wings;(it then makes a second and, in general,

unerring dart upon its prey, or regains the former altitude by an elegant spiral

flight. It seizes the fish with its claws, sometimes scarcely appearing to dip its

feet in the water, and at other times plunging entirely under the surface with force

sufficient to throw up a considerable spray *. It emerges again, however, so

speedily as to render it evident that it does not attack fish swimming at any great

depTthh.e versatility of the outer toe of the Osprey, the strength, curvature, and

sharpness of its claws, and the roughness of the soles of its feet, are peculiarities

of structure adapted to the better securing its slippery prey; and the shortness

of its thigh feathers, unusual in the falcon tribe, is also evidently connected with its

fishing habits. So firm is its hold, that it is said not unfrequently to perish by

havino- the imprudence to fix its talons in a fish of such a size and strength as to

be capable of dragging it suddenly under water. The superior strength of the

• Pennant informs us that its violent descent is compared by the Italians to the fall of lead into the water; hence

they bestow on it the appellation of Auguista piumbina (leaden Eagle). “ We never heard this name used, during six

years’ residence in Italy, and the words are not Italian.” Sw.