196

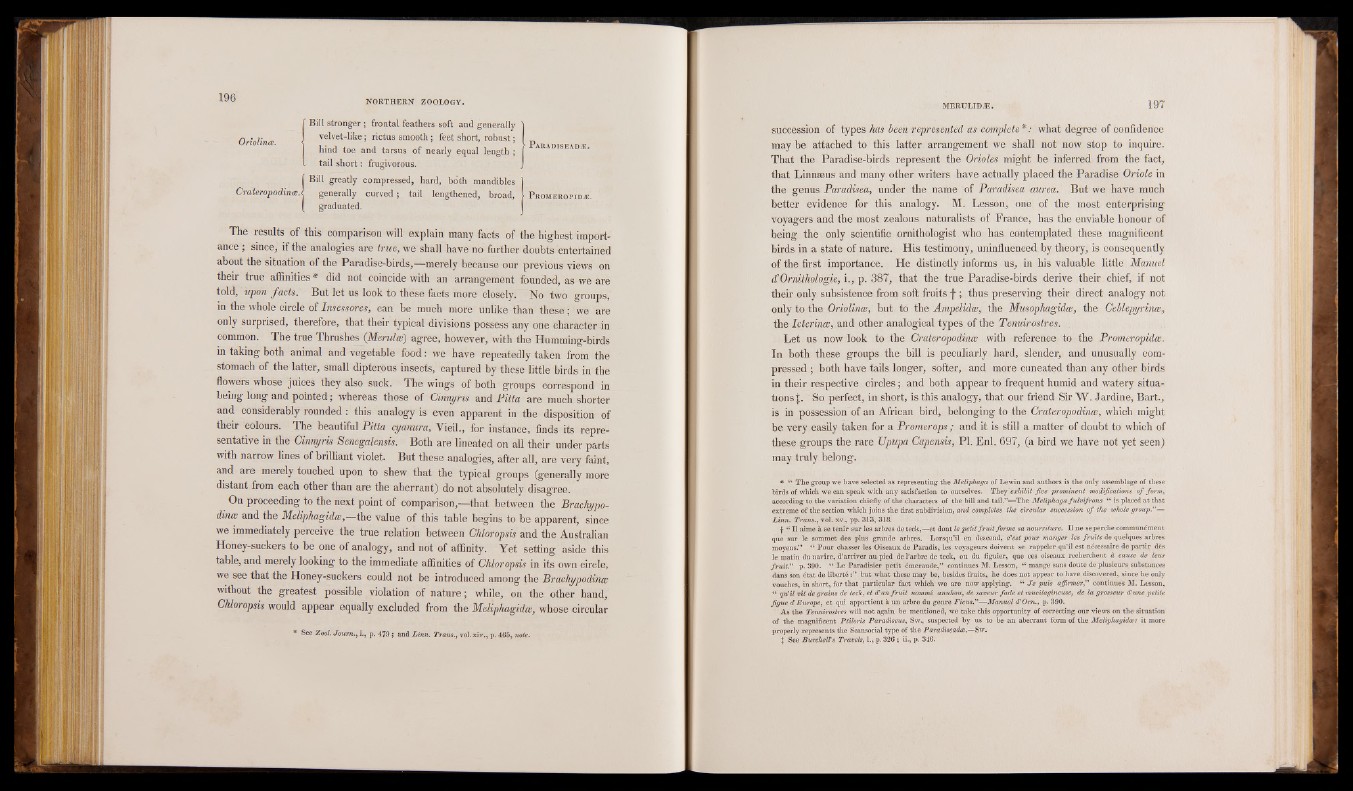

f Bill stronger ; frontal feathers soft and generally 'j

r \ • r I velvet-like; rictus smooth ; O n o llM B . i I . , if eet short, r’o bust; ’s IPar.ATiiQirat* a? hmd toe and tarsus of nearly equal length ; j

l tail short: frugivorous. J (Bill greatly compressed, hard, both mandibles ]

generally curved; tail lengthened, broad, | Promeropidrs.

graduated. I

The results of this comparison will explain many facts of the highest importance

; since, if the analogies are true, we shall lave no further doubts entertained

about the situation of the Paradise-birds,—merely because our previous views on

their true affinities * did not coincide with an arrangement founded, as we are

told, upon facts. But let us look to these facts more closely. No two groups,

in the whole circle of Insessores, can be much more unlike than these'; we are

only surprised, therefore, that their typical divisions possess any one character in

common. The true Thrushes^(Mcrulcc) agree, however, with the Humming-birds

in taking both animal and vegetable food: we have repeatedly taken from the

stomach of the latter, small dipterous insects, captured by these little birds in the

flowers whose juices they also suck. The wings of both groups correspond in

being long and pointed; whereas those of Cinnyris and Pitta are much shorter

and considerably rounded: this analogy is even apparent in the disposition of

their colours. The beautiful Pitta cyanura, Vieil., for instance, finds its representative

in the Cinnyris Senegalensis. Both are lineated on all their under parts

with narrow lines of brilliant violet. But these analogies, after all, are very faint,

and are merely touched upon to shew that the typical groups (generally more

distant from each other than are the aberrant) do not absolutely disagree.

On proceeding to the next point of comparison,—that between the Brachypo-

diniB and the Meliphagidm,—the value of this table begins to be apparent, since

we immediately perceive the true relation between Chloropsis and the Australian

Honey-suckers to be one of analogy, and not of affinity. Yet setting aside this

table, and merely looking to the immediate affinities of Chloropsis in its own circle,

we see that the Honey-suckers could not be introduced among the Brachypodinie without the greatest possible violation of nature; while, on the other hand,

Chloropsis would appear equally excluded from the Mcliphagidw, whose circular

* See ZooL Jotrni., i., p. 479 ; and Linn. Trans., vol. sir., p, 465, note.

succession of types has been represented as complete *: what degree of confidence

may be attached to this latter arrangement we shall not now stop to inquire.

That the Paradise-birds represent the Orioles might be inferred from the fact,

that Linnaeus and many other writers have actually placed the Paradise Oriole in

the genus Paradisea, under the name of Paradisea aurea. But we have much

better evidence for this) analogy. M. Lesson, one of the most enterprising

voyagers and the most zealous naturalists of France, has the enviable honour of

being the only scientific ornithologist who has contemplated these magnificent

birds in a state of nature. His testimony, uninfluenced by theory, is consequently

of the first importance. He distinctly informs us, in his valuable little Manuel

d’Ornithologie, i., p. 387, that the true Paradise-birds derive their chief, if not

their only subsistence from soft fruits -(•; thus preserving their direct analogy not

only to the Oriolincc, but to the Ampelidce, the Musophagidce, the Ceblepyrince,

the Icterinw, and other analogical types of the Tenuirostres. Let us now look to the Crateropodinw with reference to the Promeropida. In both these groups the bill is peculiarly hard, slender, and unusually compressed

; both have tails longer, softer, and more cuneated than any other birds

in their respective circles; and both appear to frequent humid and watery situations

j. So perfect, in short, is this analogy, that our friend Sir W. Jardine, Bart.,

is in possession of an African bird, belonging to the Crateropodince, which might

be very easily taken for a Promerops ; and it is still a matter of doubt to which of

these groups the rare Upupa Capensis, PL Enl. 697, (a bird we have not yet seen)

may truly belong.

* “ The group we have selected as representing the Meliphaga of Lewin and authors is the only assemblage of these

birds of which we can speak with any satisfaction to ourselves. They exhibit five prominent modifications of form,

according to the variation chiefly of the characters of the bill and tail.”—The Meliphaga fulvifrons “ is placed at that

extreme of the section which joins the first subdivision, and completes the circular succession of the whole group."—

Linn. Trans., vol. xv., pp. 313, 318.

■}• “ Il aime à se tenir sur les arbres de teck,—et dont le petit fruit forme sa nourriture. Il ne se perche communément

que sur le sommet des plus grande arbres. Lorsqu’il en descend, c'est pour manger les fruits de quelques arbres

moyens.” “ Pour chasser les Oiseaux de Paradis, les voyageurs doivent se rappeler qu’il est nécessaire de partir dès

le matin du navire, d’arriver au pied de l’arbre de teck, ou du figuier, que ces oiseaux recherchent à cotise de leur

fruit." p. 390. “ Le Paradisier petit émeraude,” continues M. Lesson, “ mange sans doute de plusieurs substances

dans son état de liberté but what these may be, besides fruits, he does not appear to have discovered, since he only

vouches, in short, for that particular fact which we are now applying. “ Je puis a ffirm e rcontinues M. Lesson,

“ qu’il vit de grains de teck, et d’un fruit nommé anuhou, de saveur fade et mucilagineuse, de la grosseur d'une petite

figue dEurope, et qui appartient à un arbre du genre Ficus."—Manuel d’Orn., p. 390.

As the Tenuirostres will not again be mentioned, we take this opportunity of correcting our views on the situation

of the magnificent Ptiloris Paradiseus, Sw., suspected by us to be an aberrant form of the Meliphagidw: it more

properly represents the Scansorial type of the Paradiseadce.—Sw.

J See Burchetts Travels, i., p. 326 ; ii., p. 346.