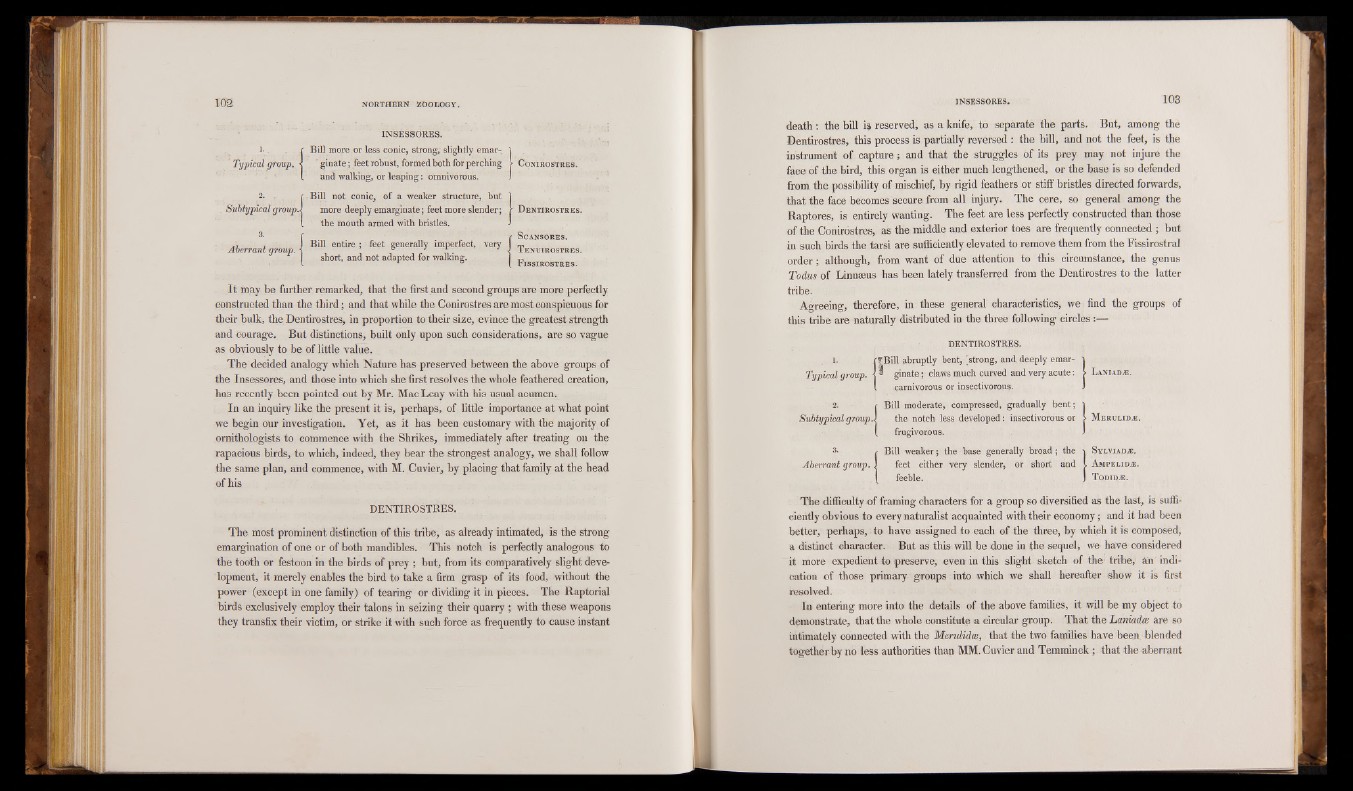

INSESSORES.

1*. / BilJ more,or less conic, strong; slightly emar-.

Typical group. ■! 'ginate; feet robust, formed both for perching

l and walking, or leaping: omnivorous.

Bill not conic, of a weaker structure, but

more deeply emarginate; feet more slender;

the mouth armed with bristles.

Subtypical group.*

I Conirostres.

| Dentirostres.

{ Bcansores.

Tenuirostres.

Fissirostres. .

,, , i Bill entire Aberrant group, t ; feet °g enerally imnp e• rfe'ct, very I short, and not adapted for walking.

It may be further remarked, that the first and second groups are more perfectly

constructed than the third; and that while the Conirostres are most conspicuous for

their bulk, the Dentirostres, in proportion to their size, evince the greatest strength

and courage. But distinctions, built only upon such considerations, are so vague

as obviously to be of little value.

The decided analogy which Nature has preserved between the above groups of

the Insessores, and those into which she first resolves the whole feathered creation,

has recently been pointed out by Mr. Mac Leay with his usual acumen.

In an inquiry like the present it is, perhaps, of little importance at what point

we begin our investigation. Yet, as it has been customary with the majority of

ornithologists to commence with the Shrikes, immediately after treating on the

rapacious birds, to which, indeed, they bear the strongest analogy, we shall follow

the same plan, and commence, with M. Cuvier, by placing that family at the head

of his

DENTIROSTRES.

The most prominent distinction of this tribe, as already intimated, is the strong

emargination of one or of both mandibles. This notch is perfectly analogous to

the tooth or festoon in the birds of prey; but, from its comparatively slight development,

it merely enables the bird to take a firm grasp of its food, without the

power (except in one family) of tearing or dividing it in pieces. The Raptorial

birds exclusively employ their talons in seizing their quarry; with these weapons

they transfix their victim, or strike it with such force as frequently to cause instant

death: the bill is reserved, as a knife, to separate the parts. But, among the

Dentirostres, this process is partially reversed : the bill, and not the feet, is the

instrument of capture; and that the struggles of its prey may not injure the

face of the bird, this organ is either much lengthened, or the base is so defended

from the possibility of mischief, by rigid feathers or stiff bristles directed forwards,

that the face becomes secure from all injury. The cere, so general among the

Raptores, is entirely wanting. The feet are less perfectly constructed than those

of the Conirostres, as the middle and exterior toes are frequently connected ; but

in such birds the tarsi are sufficiently elevated to remove them from the Fissirostral

order; although, from want of due attention to this circumstance, the genus

Todus of Linnaeus has been lately transferred from the Dentirostres to the latter

tribAeg.reeing, therefore, in these general characteristics, we . find the groups of

this tribe are naturally distributed in the three following circles:—

DENTIROSTRES.

1. ffBill abruptly bent, [strong, and, deeply emar

Typical group. j * ginate; claws much curved and very acute

l carnivorous or insectivorous.

2 . r Bill moderate, compressed, gradually bent

Subtypical group.) the notch less developed: insectivorous o

1 frugivorous.

3- , Bill weaker; the base generally broad ; th

Aberrant group. \ feet either very slender, or short an'

| feeble.

| L aNIADvE.

I Merulidas.

{ Sylviap.®.

Ampelid.®.

TODIDyE.

The difficulty of framing characters for a group so diversified as the last, is sufficiently

obvious to every naturalist acquainted with their economy; and it had been

better, perhaps, to have assigned to each of the three, by which it is composed,

a distinct character. But as this will be done in the sequel, we have considered

it more expedient to preserve, even in this slight sketch of the tribe, an indication

of those primary groups into which we shall hereafter show it is first

resolved.

In entering more into the details of the above families, it will be my object to

demonstrate, that the whole constitute a circular group. That the Laniadce are so

intimately connected with the Merulidw, that the two families have been blended

together by no less authorities than MM. Cuvier and Temminck; that the aberrant