We have before stated our conviction that the Merulidee and the Laniad.ee are

the two typical groups of the Dentirostres. To shew that there is good ground

for this belief, we shall now state the general analogies between the leading groups of these families.

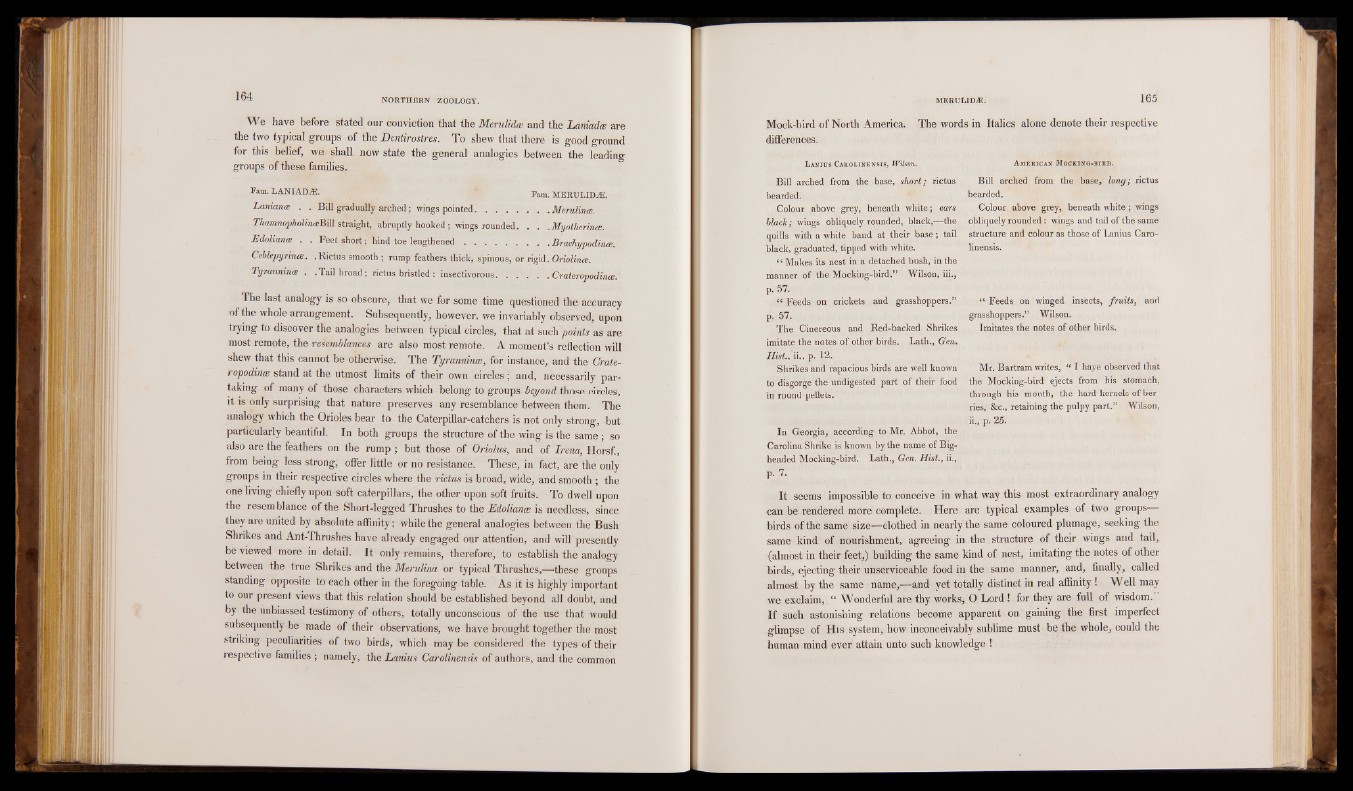

Fam. LANIAD-®. ‘ Fam. MERULIDjE.

Laniaiue . . Bill gradually arched ; wings pointed......................... .Merulinae.

ThamnopholinceBill straight, abruptly hooked ; wings rounded. . . .Myotherinee.

Edolianee . . Feet short; hind toe lengthened..................................Brachypodinee.

Ceblepyrinee. .Rictus smooth ; rump feathers thick, spinous, or rigid. Oriolinee.

Tyrannies: . .Tail broad ; rictus bristled : insectivorous. . . . . . Crateropadinm.

The last analogy is so obscure, that we for some time questioned the accuracy

of the whole arrangement. Subsequently, however, we invariably observed, upon

trying to discover the analogies between typical circles, that at such points as are

most remote, the resemblances are also most remote. A moment’s reflection will

shew that this cannot be otherwise. The Tyranninee, for instance, and the Crate-

ropodincB stand at the utmost limits of their own circles; and, necessarily partaking

of many of those characters which belong to groups beyond those circles,

it is only surprising that nature preserves any resemblance between them. The

analogy which the Orioles bear to the Caterpillar-catchers is not only strong, but

particularly beautiful. In both groups the structure of the wing is the same ; so

also are the feathers on the rump ; but those of Oriolus, and of Irena, Horsf.,

from being less strong, offer little or no resistance. These, in fact, are the only

groups in their respective circles where the rictus is broad, wide, and smooth ; the

one living chiefly upon soft caterpillars, the other upon soft fruits. To dwell upon

the resemblance of the Short-legged Thrushes to the Edolianee is needless, since

they are united by absolute affinity; while the general analogies between the Bush

Shrikes and Ant-Thrushes have already engaged our attention, and will presently

be viewed more in detail. It only remains, therefore, to establish the analogy

between the true Shrikes and the Merulina or typical Thrushes,—these groups

standing opposite to each other in the foregoing table. As it is highly important

to our present views that this relation should be established beyond all doubt, and

by the unbiassed testimony of others, totally unconscious of the use that would

subsequently be made of their observations, we have brought together the most

striking peculiarities of two birds, which may be considered the types of their

respective families ; namely, the Lanins Carolinemis of authors, and the common

Mock-bird of North America. The words in Italics alone denote their respective

differences.

LaNIUS CaROLINENSIS, Wilson.

Bill arched from the base, short; rictus

bearded.

Colour above grey, beneath white; ears

black; wings obliquely rounded, black,—the

quills with a white band at their base; tail

black, graduated, tipped with white.

“ Makes its nest in a detached bush, in the

manner of the Mocking-bird.” Wilson, iii.,

p. 57.

<c Feeds on crickets and grasshoppers.”

p. 57.

The Cinereous and Red-backed Shrikes

imitate the notes of other birds. Lath., Gen.

Hist, ii„ p. 12.

Shrikes and rapacious birds are well known

to disgorge the undigested part of their food

in round pellets.

In Georgia, according to Mr. Abbot, the

Carolina Shrike is known by the name of Bigheaded

Mocking-bird. Lath., Gen. Hist, ii.f

A m e r ica n M o ck in g -b ir d .

Bill arched from the base, long; rictus

bearded.

Colour above grey, beneath white; wings

obliquely rounded: wings and tail of the same

structure and colour as those of Lanius Caro-

linensis.

te Feeds on winged insects, fruits, and

grasshoppers.” Wilson.

Imitates the notes of other birds.

Mr. Bar tram writes, " I haye observed that

the Mocking-bird ejects from his stomach,

through his mouth, the hard kernels of berries,

&c., retaining the pulpy part.” Wilson,

ii„ p. 25.

p. 7.

It seems impossible to conceive in what way this most extraordinary analogy

can be rendered more complete. Here are typical examples of two groups

birds of the same size—clothed in nearly the same coloured plumage, seeking the

same kind of nourishment, agreeing in the structure of their wings and tail,

(almost in their feet,) building the same kind of nest, imitating the notes of other

birds, ejecting their unserviceable food in the same manner, and, finally, called

almost by the same name,—and yet totally distinct in real affinity ! Well may

we exclaim, “ Wonderful are thy works, O Lord ! for they are full of wisdom.

If such astonishing relations become apparent on gaining the first imperfect

glimpse of His system, how inconceivably sublime must be the whole, could the

human mind ever attain unto such knowledge !