forms of the Merulidce, as Timalia and Megalurus, have been considered true

Sylviadoe, either by MM. Temminck, Horsfield, or Vigors ; that one of the principal

genera among the Sylviadoe has been mistaken by the latter gentleman for

a group belonging to the Ampelidoe ; and, finally, that the Todidoe are so closely

united with the Tyrant Shrikes, by means of such genera as Fluvicola and N en-

getus, that not only Linnæus, but every subsequent writer of his school, has placed

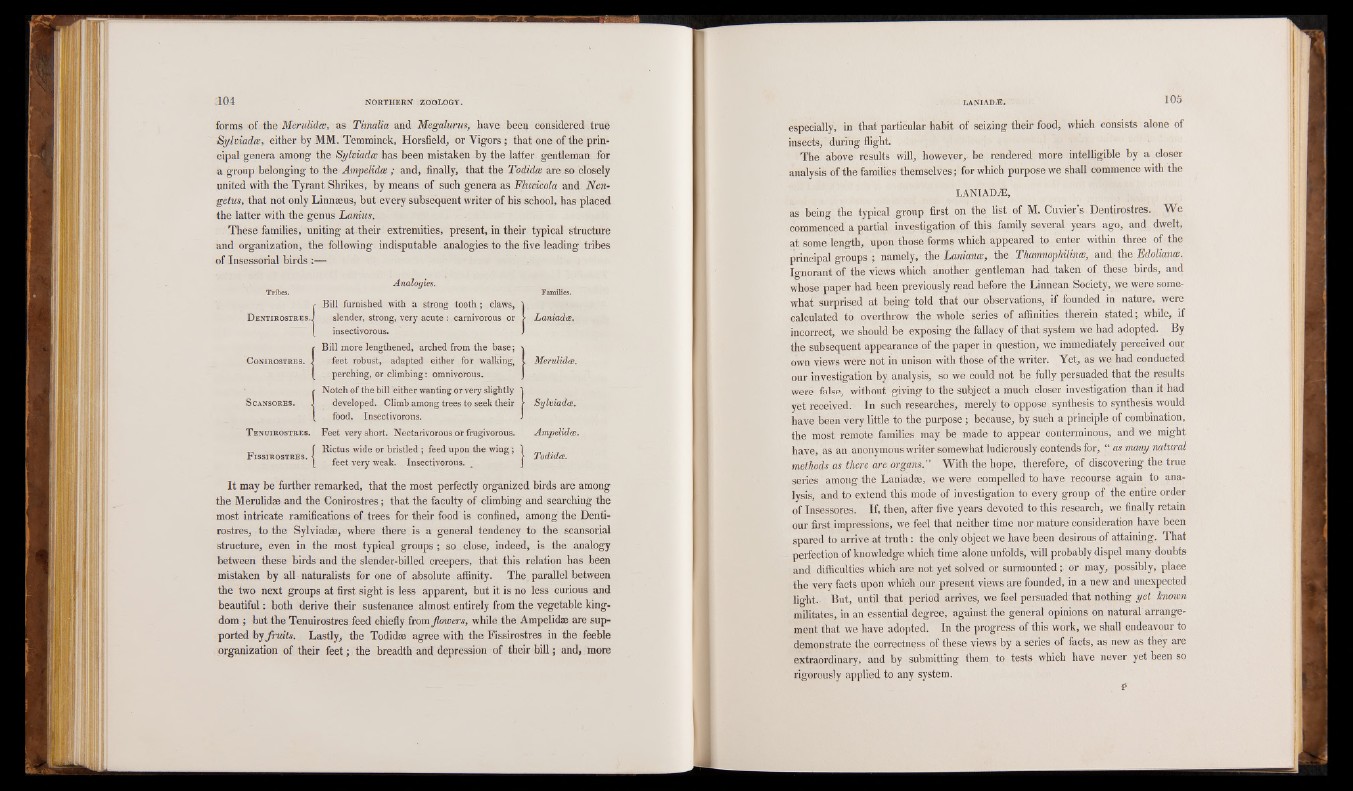

the latter with the genus Lanius. These families, uniting at their extremities, present, in their typical structure

and organization, the following indisputable analogies to the five leading tribes

of Insessorial birds :—

Tribes.

DentirostresJ

Analogies.

Bill furnished with a strong tooth ; claws,

slender, strong, very acute : carnivorous or

insectivorous.

r Bill more lengthened, arched from the base;

Conirostres. J feet robust, adapted either for walking,

. . perching, or climbing: omnivorous.

r Notch of the bill either wanting or very slightly

Scansores. J developed. Climb among trees to seek their

t food. Insectivorous.

Families.

Laniadoe,

Merulidce.

Sylviadoe.

Tenuirostres. Feet very short. Nectarivorous or frugivorous.

FissirostresI Rictus wide or bristled ; feed upon the wing

feet very weak. Insectivorous. ‘ 1

Ampelidoe.

Todidoe.

It may be further remarked, that the most perfectly organized birds are among

the Merulidae and the Conirostres; that the faculty of climbing and searching the

most intricate ramifications of trees for their food is confined, among the Denti-

rostres, to the Sylviadae, where there is a general tendency to the scansorial

structure, even in the most typical groups; so close, indeed, is the analogy

between these birds and the slender-billed creepers, that this relation has been

mistaken by all naturalists for one of absolute affinity. The parallel between

the two next groups at first sight is less apparent, but it is no less curious and

beautiful: both derive their sustenance almost entirely from the vegetable kingdom

; but the Tenuirostres feed chiefly from flowers, while the Ampelidae are supported

by fruits. Lastly, the Todidse agree with the Fissirostres in the feeble

organization of their feet; the breadth and depression of their bill; and, more

especially, in that particular habit of seizing their food, which consists alone of

insects, during flight.

The above results will, however, be rendered more intelligible by a closer

analysis of the families themselves; for which purpose we shall commence with the

l a n ia d a :,

as being the typical group first, on the list of M. Cuvier’s Dentirostres. We

commenced a partial investigation of this family several years ago, and dwelt,

at some length, u p o n those forms which appeared to enter within three of the

principal groups ; namely, the Lammas, the Thmnnophilinw, and the Edoliance. Ignorant of the views which another gentleman had taken of these birds, and

whose paper had been previously read before the Linnean Society, we were somewhat

surprised at being told that our observations, if founded in nature, were

calculated to overthrow the whole series of affinities therein stated; while, if

incorrect, we should be exposing the fallacy of that system we had adopted. By

the subsequent appearance of the paper in question, we immediately perceived our

own views were not in unison with those of the writer. Yet, as we had conducted

our investigation by analysis, so we could not be fully persuaded that the results

were false, without giving to the subject a much closer investigation than it had

yet received. In such researches, merely to oppose synthesis to synthesis would

have been very little to the purpose; because, by such a principle of combination,

the most remote families may be made to appear conterminous, and we might

have, as an anonymous writer somewhat ludicrously contends for, “ as many natural

methods as there are organs." With the hope, therefore, of discovering the true

series among the Laniadac, we were compelled to have recourse again to analysis,

and to extend this mode of investigation to every group of the entire order

of Insessores. If, then, after five years devoted to this research, we finally retain

our first impressions, we feel that neither time nor mature consideration have been

spared to arrive at truth : the only object we have been desirous of attaining. That

perfection of knowledge which time alone unfolds, will probably dispel many doubts

and difficulties which are not yet solved or surmounted; or may, possibly, place

the very facts upon which our present views are founded, in a new and unexpected

light. But, until that period arrives, we feel persuaded that nothing yet known militates, in an essential degree, against the general opinions on natural arrangement

that we have adopted. In the progress of this work, we shall endeavour to

demonstrate the correctness of these views by a series of facts, as new as they are

extraordinary, and by submitting them to tests which have never yet been so

rigorously applied to any system.