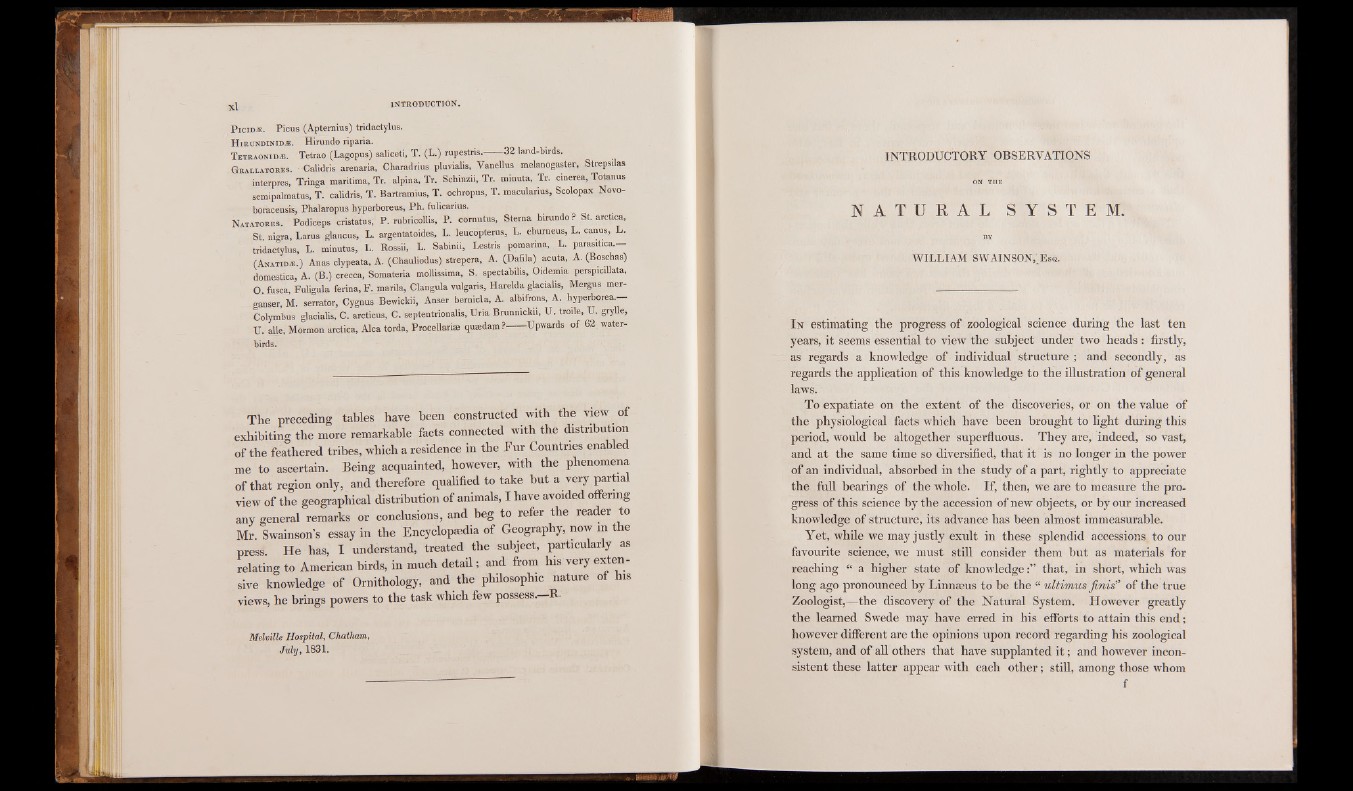

P icidæ . Picus (Aptemius) tridactylus.

H irundinidæ. Hirundo riparia.

Tetraonidæ. Tetrao (Lagopus) saliceti, Ï . (L.) rupestris.------32 land-birds.

Grallatores. Calidris arenaria, Charadrius pluvialis, Yanellus melanogaster, Strepsilas

interpres, Tringa maritima, Tr. alpha, Tr. Schinzii, Tr. minuta, Tr. cinerea, Totanus

semipalmatus, T. calidris, T. Bartramius, T. ochropus, T. macularius, Scolopax Novo-

boracensis, Phalaropus hyperboreus, Ph. fulicarius.

N atatores. Podiceps cristatusV P. rubricollis, P. cornutus, Sterna hirundo? St. arctica,

St nigra, Laras glaucus, L. argentatoides, L. leucopterus, L. eburneus, L. canus, L.

tridactylus, L. minutas, L. Rossii, L. Sabinii, Lestris pomarina, L. parasitica.—

(Anatidæ.) Anas clypeata, A. (Chauliodus) strepera, A. (Dafila) acuta, A. (Boschas)

domestica, A. (B.) crecca, Somateria mollissima, S. spectabilis, Oidemia perspicillata,

O. fusca, Fuligula ferina, F. marila, Clangula vulgaris, Harelda glacialis, Mergus merganser,

M. serrator, Cygnus Bewickii, Anser bernicla, A. albifrons, A. hyperborea.—

Colymbus glacialis, C. arcticus, C. septentrionalis, Uria Brannickn, U. trolle, U. grylle,

U. alle, Mormon arctica, Alca tarda, Procellariæ quædam?------Upwards of 62 waterbirds.

The preceding tables have been constructed with the view of

exhibiting the more remarkable facts connected with the distribution

of the feathered tribes, which a residence in the Fur Countries enabled

me to ascertain. Being acquainted, however, with the phenomena

of that region only, and therefore qualified to take but a very partial

view of the geographical distribution of animals, I have avoided offering

any general remarks or conclusions, and beg to refer the reader to

Mr. Swainson's essay in the Encyclopaedia of Geography, now in the

press. He has, I understand, treated the subject, particularly as

relating to American birds, in much detail ; and from his very extensive

knowledge of Ornithology, and the philosophic nature of his

views, he brings powers to the task which few possess. RMelville

Hospital, Chatham,

July, 1831.

INTRODUCTORY OBSERVATIONS

ON THE

N A T U R A L S Y S T EM.

■ BY

WILLIAM SWAINSON^Esq.

I n estimating the progress of zoological science during the last ten

years, it seems essential to view the subject under two heads : firstly,

as regards a knowledge of individual structure ;’ and secondly, as

regards the application of this knowledge to the illustration of general

laws.

To expatiate on the extent of the discoveries, or on the value of

the physiological facts which have been brought to light during this

period, would be altogether superfluous. They are, indeed, so vast,

and at the same time so diversified, that it is no longer in the power

of an individual, absorbed in the study of a part, rightly to appreciate

the full bearings of the whole. If, then, we are to measure the progress

of this science by the accession of new objects, or by our increased

knowledge of structure, its advance has been almost immeasurable.

Yet, while we may justly exult in these splendid accessions to our

favourite science, we must still consider them but as materials for

reaching “ a higher state of knowledgethat, in short, which was

long ago pronounced by Linnaeus to be the “ ultimus finis” of the true

Zoologist,—the discovery of the Natural System. However greatly

the learned Swede may have erred in his efforts to attain this end;

however different are the opinions upon record regarding his zoological

system, and of all others that have supplanted i t ; and however inconsistent

these latter appear with each other; still, among those whom

f