The three subordinate divisions of the aberrant group contain, as usual, genera

of much apparent dissimilarity ; they may, however, be defined as birds having

the bill much thicker and more powerful than those of the typical groups, while

their general structure is weaker and more imperfect. This inferiority is evinced,

among the Fringillidoe, by their diminutive size ; in the Musophagidoe, by the feet

being adapted only for frequenting trees, and in the restriction of their food to vegetables;

while in the bulky Hornbills (Buceridæ) the tarsi are unusually short and

the toes nearly syndactyle. None of these imperfections are observed among the

Corvidoe and the Sturnidoe. We therefore agree with Mr. Vigors in considering

that these families represent the perfection of the ornithologie structure*.

The precise manner in which the aberrant circle is closed, by the union of the

Fringillidoe and the Buceridæ, cannot at present be explained ; their absolute

affinity, however, has been already acknowledged, and their union insisted uponf.

As to the Musophagidoe, comprising the genera Musophaga, Corythaix, Coitus, and Phytotoma, any ornithologist, who actually examines these birds, must be

convinced that they offer so many steps of gradation between the Buceridæ and

the Fringillidoe, yet too distinct to be comprehended under either of those families.

We must pass over the analogical relations of the Conirostral group, and

merely confine ourselves to a few remarks upon the

FR INGILLIM .

as being that family which offers the greater number of species brought, home by

the Expeditions. The primary divisions of this group, which is certainly the

most extensive in the whole circle of Ornithology, may be thus stated:—

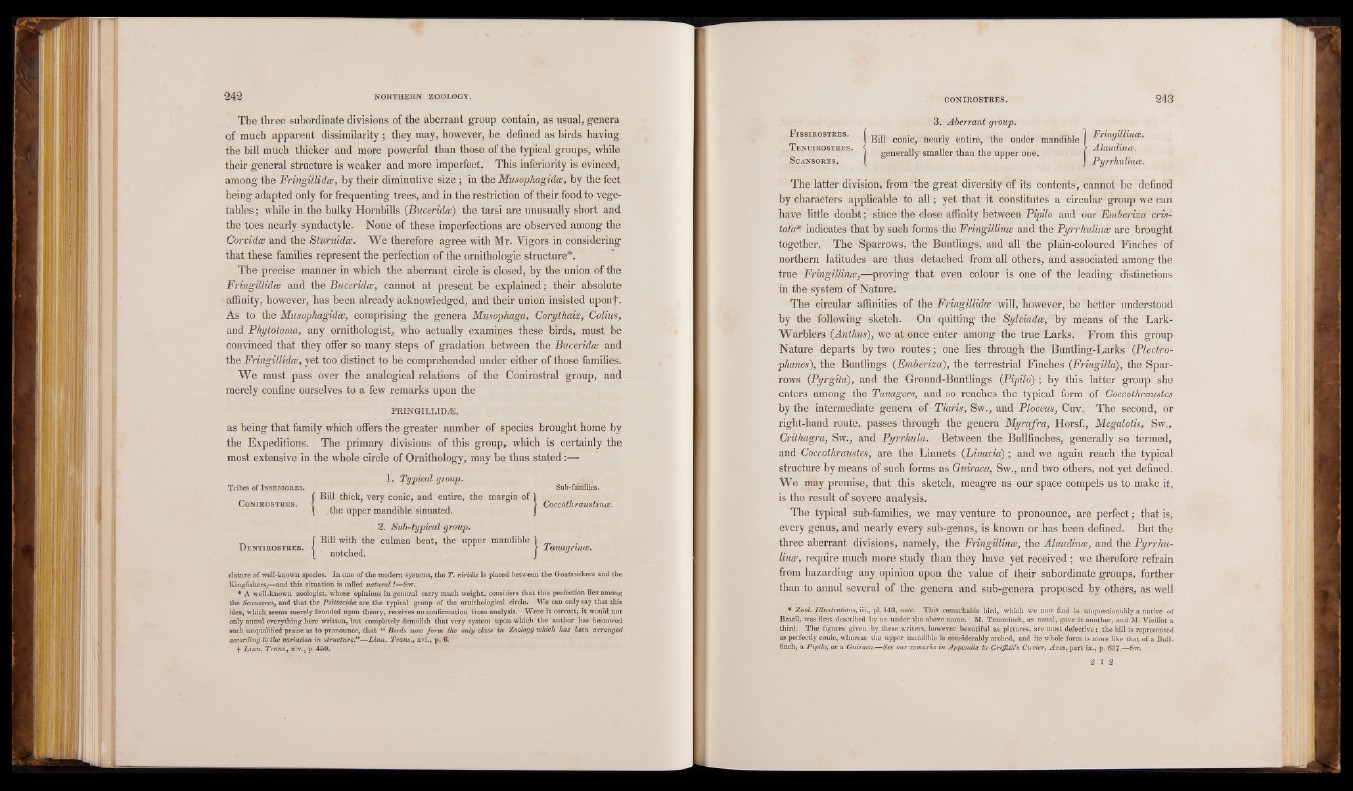

1. Typical gioup.

Tribes of Insessob.es.

Sab-families.

CONIROSTRES,Bill thick, very conic, and entire, the margin of

■ {

, the upper mandible sinuated.

Coccothraustinoe.

Dentirostres, {

2. Sub-typical group*

Bill with the culmen bent, the upper mandible

notched.

I Tanagrince.

clature of well-known species. In one of the modern systems, the T. viridis is placed between the Goatsuckers and the

Kingfishers,—and this situation is called natural!—Sw.

* A well-known zoologist, whose opinions in general carry much weight, considers that this perfection lies among

the Scansores, and that the Psittacidce are the typical group of the ornithological circle. We can only say that this

idea, which seems merely founded upon theory, receives no confirmation from analysis. Were it correct, it would not

only annul everything here written, but completely demolish that very system upon which the author has bestowed

such unqualified praise as to pronounce, that “ Birds now form the only class in Zoology which has been arranged

according to the variation in structure.”—Linn. Trans., xvi., p. 6.

f IAnn. Trans., xiv., p. 450.

3. Aberrant group.

Fissirostres. t,.,, , I Bill conic, neatil y entire, t,,h e undi er mandj.i,b,l e 1I Frinqitillince. Tenuirostres. \I generalnly; s ma,l,l er t,h, an t.h, e upper one. j> Alaudince. Scansores . [ , , J Pyrrhulince.

The latter division, from the great diversity of its contents, cannot be defined

by characters applicable to all; yet that it constitutes a circular group we can

have little doubt; since the close affinity between Pipilo and our Emberiza cristate*

indicates that by such forms the Fringillince and the Pyrrhulince are brought

together. The Sparrows, the Buntlings, and all the plain-coloured Finches of

northern latitudes are thus detached from all others, and associated among the

true Fringillince,-—proving that even colour is one of the leading distinctions

in the system of Nature,

The circular affinities of the Fringillidas will, however, be better understood

by the following sketch. On quitting the Sylmadce, by means of the Lark-

Warblers (Anthus), we at once enter among the true Larks. From this group

Nature departs by two routes; oue lies through the Buntling-Larks : (Plectra-

phanes), the Buntlings (Emberiza), the terrestrial Finches (Fringilla), the Sparrows

(Pyrgita), and the Ground-Buntlings (Pipilo) ; by this latter group she

enters among the Tarmgers, and so reaches the typical form of Coccothraustes

by the intermediate genera of Tiaris, Sw., and Ploceus, Guv. The second, or

right-hand route, passes through the genera Myrafra, Horsf., Megalotis, Sw.,

Crithagra, Sw., and Pyrrhula. Between the Bullfinches, generally so termed,

and Coccothraustes, are the Linnets (Einaria); and we again reach the typical

structure by means of such forms as Guiraca, Sw., and two others, not yet defined.

We may premise, that this sketch, meagre as our space compels us to make it,

is the result of severe analysis.

The typical sub-families, we may venture to pronounce, are perfect; that is,

every genus, and nearly every sub-genus, is known or has been defined. But the

three aberrant divisions, namely, the Fringillinm, the Alaudince, and the Pyrrhulince,

require much more study than they have yet received ; we therefore refrain

from hazarding any opinion upon the value of their subordinate groups, further

than to annul several of the genera and sub-genera proposed by others, as well

* Zool. Illustrations, iii., pi. 148, note. This remarkable bird, which we now find is unquestionably a native of

Brazil, was first described by us under the above name. Ml Temminck, as usual, gave it another, and -M. Yieillot a

third. The figures given by these writers, however beautiful as pictures, are most defective: the bill is represented

as perfectly conic, whereas the upper mandible is considerably arched, and its whole form is more like that of a Bullfinch,

a Pipilo, or a Guiraca.—See our remarks in Appendix to Griffith’s Cuvier, Aves, part ix., p. 687.—Sw.