Under‘plumage hair-brown, mixed on the ears and sides of the neck with yellowish-brown ;

under tail coverts darker; axillaries and inner wing coverts pitch-black. Interior of the

quills greyish-brown, paler than any other part of the plumage. Bill greenish-black. Legs

and feet shining velvet-black.

Form, typical.—Bill, towards the base, nearly cylindrical, being very slightly higher than

broad; culmen rounded ; upper mandible, towards the end, rather hooked, and destitute of

a distinct notch; the cutting margins at that part being slightly indexed, so as to produce

the appearance of an obsolete notch, although the margins are actually entire. (This formation

is frequently seen in the Pigeon family.—Sw.) Wings an inch longer than the lateral tail

feathers; primaries acute, secondaries truncated. Tail of twelve feathers ; the central pair,

three inches longer than the adjoining ones, much acuminated ; the others are more or

less truncated and emarginate, the tip of the shaft projecting into a short acuminated

mucro or point; the tail is graduated, the exterior feathers being eight lines shorter than

the pair next the middle. Thighs bare for eight lines. Tarsi protected anteriorly by

strong falciform or~crescentic scutelli; reticulated behind, as well as the knee and tarsal

joints; the soles of the feet and sides of the toes and membranes are covered with small

thick scales, which have each a raised central ridge, or a sharp point.

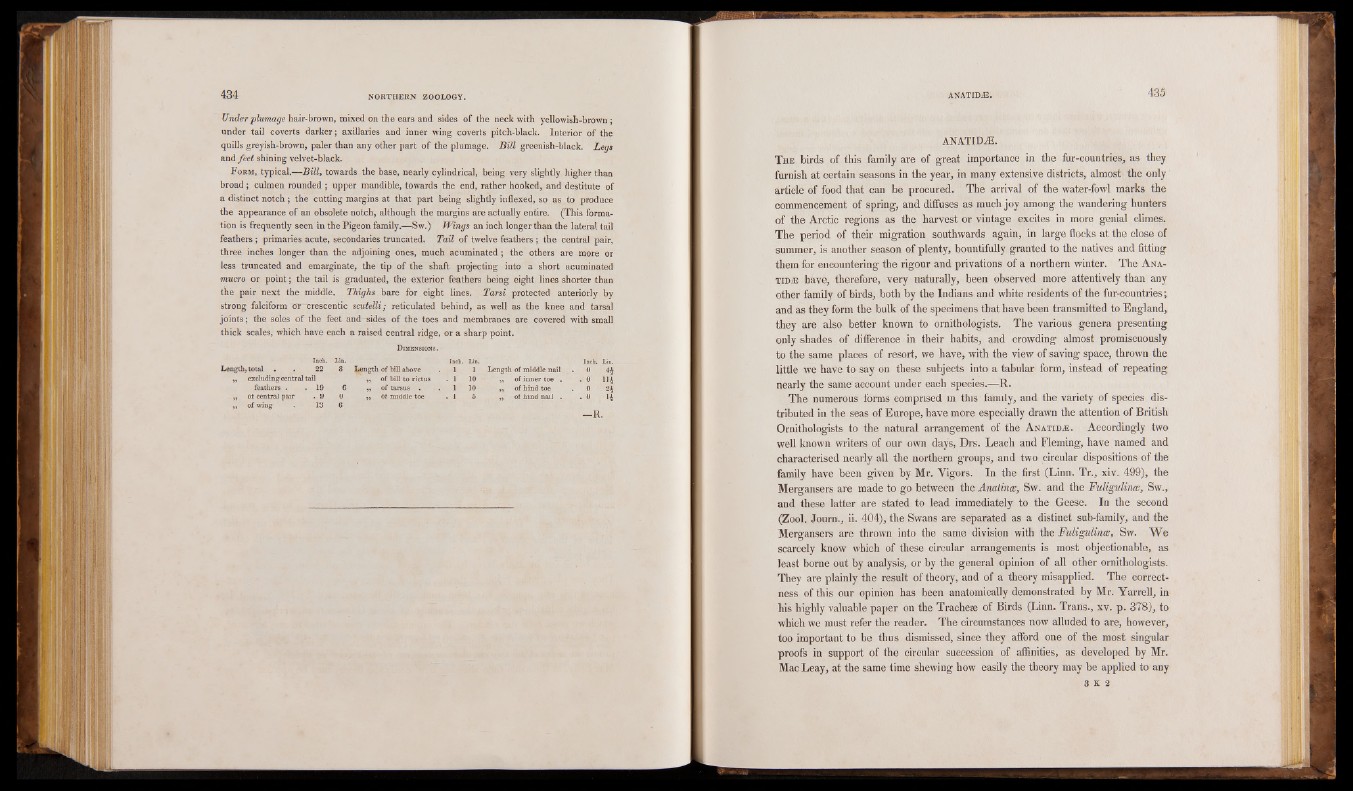

Dimensions.

Length, total 22 8 Length of bill above

Inch. Lin.

1 1 Length of middle nail

Inch. !

0 „ excluding central tail ,, of bill to rictus . 1 10 ■ ' ,, of inner toe . . 0 feathers . . 19 6 ,, of tarsus . 1 10 T, of hind toe 0 _„ of central pair . 9 0 „ of middle toe . 1 5 „ of hind nail . ,, of wing 13 6 • o

— R.

ANATIDjE.

The birds of this family are of great importance in the fur-countries, as they

furnish at certain seasons in the year, in many extensive districts, almost the only

article of food that can be procured. The arrival of the water-fowl marks the

commencement of spring, and diffuses as much joy among the wandering hunters

of the Arctic regions as the harvest or vintage excites in more genial climes.

The period of their migration southwards again, in large flocks at the close of

summer, is another season of plenty, bountifully granted to the natives and fitting

them for encountering the rigour and privations of a northern winter. The A na- TiD/E have, therefore, very naturally, been observed more attentively than any

other family of birds, both by the Indians and white residents of the fur-countries;

and as they form the bulk of the specimens that have been transmitted to England,

they are also better known to ornithologists. The various genera presenting

only shades of difference in their habits, and crowding almost promiscuously

to the same places of resort, we have, with the view of saving space, thrown the

little we have to say on these subjects into a tabular form, instead of repeating

nearly the same' account under each species.—R.

The numerous forms comprised in this family, and the variety of species distributed

in the seas of Europe, have more especially drawn the attention of British

Ornithologists to the natural arrangement of the A natid,®. Accordingly two

well known writers of our own days, Drs. Leach and Fleming, have named and

characterised nearly all the northern groups, and two circular dispositions of the

family have been given by Mr. Vigors. In the first (Linn. Tr., xiv. 499), the

Mergansers are made to go between the Anatinw, Sw. and the Fuligulinw, Sw.,

and these latter are stated to lead immediately to the Geese. In the second

(Zool. Journ., ii. 404), the Swans are separated as a distinct sub-family, and the

Mergansers are thrown into the same division with the Fuligulinw, Sw. We

scarcely know which of these circular arrangements is most objectionable, as

least borne out by analysis, or by the general opinion of all other ornithologists.

They are plainly the result of theory, and of a theory misapplied. The correctness

of this our opinion has been anatomically demonstrated by Mr. Yarrell, in

his highly valuable paper on the Tracheae of Birds (Linn. Trans., xv. p. 378), to

which we must refer the reader. The circumstances now alluded to are, however,

too important to be thus dismissed, since they afford one of the most singular

proofs in support of the circular succession of affinities, as developed by Mr.

Mac Leay, at the same time shewing how easily the theory may be applied to any

3 K 2