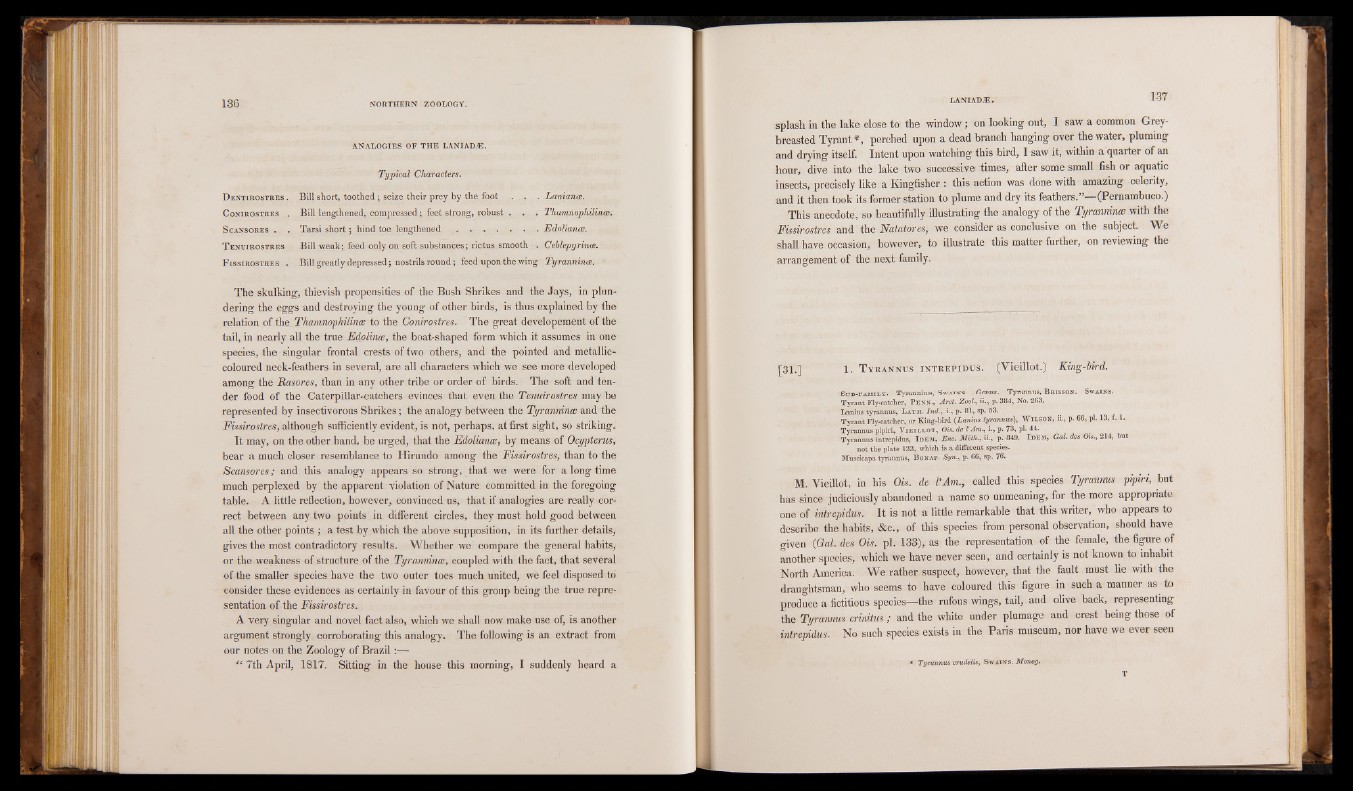

ANALOGIES OF THE LANIADA3.

Typical Characters.

Dentirostres . Bill short, toothed ; seize their prey by the foot . . . Laniance.

Conirostres , Bill lengthened,- compressed ; feet strong, robust . . . Thumnophiliner.

Scansores . . Tarsi short; hind toe lengthened . ......................Edaliance.

T enujrostres Bill weak; feed only on soft substances; rictus.smooth .. Ceblepyrinee.-

F issirostres . Bill greatly depressed; nostrils round; feed upon the wing TyrannintB. ■

The skulking, thievish propensities of the Bush Shrikes and the Jays, in plundering

the eggs and destroying the young of other birds, is thus explained by the

relation of the Thamnophilina: to the Conirostres. The great developement of the

tail, in nearly all the true EdolintB, the boat-shaped form which it assumes in one

species, the singular frontal crests of two others, and the pointed and metallic-

coloured neck-feathers in several, are all characters which we see more developed

among the Rasores, than in any other tribe or order of birds. The soft and tender

food of the Caterpillar-catchers evinces that even the Tenuirostres may be

represented by insectivorous Shrikes; the analogy between the TyrannintB and the

Fissirostres, although sufficiently evident, is not, perhaps, at first sight, so striking.

It may, on the other hand, be urged, that the Edoliance, by means of Ocypterus, bear a much closer resemblance to Hirundo among the Fissirostres, than to the

Scansores; and this analogy appears so strong, that we were for a long time

much perplexed by the apparent violation of Nature committed in the foregoing

table. A little reflection, however, convinced us, that if analogies are really correct

between any two points in different circles, they must hold good between

all the other points ; a test by which the above supposition, in its further details,

gives the most contradictory results. Whether we compare the general habits,

or the weakness of structure of the TyrannintB, coupled with the fact, that several

of the smaller species have the two outer toes much united, we feel disposed to

consider these evidences as certainly in favour of this group being the true representation

of the Fissirostresg,

A very singular and novel fact also, which we shall now make use of, is another

argument strongly corroborating this analogy. The following is an extract from

our notes on the Zoology of Brazil:—

“ 7th April, 1817. Sitting in the house this morning, I suddenly heard a

splash in the lake close to the window; on looking out, I saw a common Greybreasted

Tyrant *, perched upon a dead branch hanging over the water, pluming

and drying itself. Intent upon watching this bird, I saw it, within a quarter of an

hour, dive into the lake two successive times, after some small fish or aquatic

insects, precisely like a Kingfisher : this action was done with amazing celerity,

and it then took its former station to plume and dry its feathers.”—(Pernambuco.)

This anecdote, so beautifully illustrating the analogy of the TyrannintB with the

Fissirostres and the Natatores, we consider as conclusive on the subject. We

shall have occasion, however, to illustrate this matter further, on reviewing the

arrangement of the next family.

[31.] 1. T yrannus intrepidus. (Vieillot.) King-bird.

• Su b -fa m il Y. Tyranninsfij Sw ain s. Gen/us. Tyrannus, B r isso n . Sw ain s.

Tyrant Fly-catcher, P e n n ., Arct. Zool, ii., p. 384, No. 263.

Lanius tyrannus, L a th . Ind., i., p. 81, sp. 53.

Tyrant Fly-catcher, or King-bird (Lanius tyrannus), W il s o n , ii., p. 66, pi. 13, f. 1.

Tyrannus pipiri, V ie il l o t , Ois. de VArn., i., p. 73, pi. 44. Tyrannus intrepidus, I d em , Enc. M'eth., ii., p. 849. I d em , Gal. desOis., 214, but

not the plate 133, which is a different species.

Musdcapa tyrannus, B o na p. Syn., p. 66, sp. 76.

M. Vieillot, in his Ois. de VAm., called this species Tyrannus pipiri, but

has since judiciously abandoned a name so unmeaning, for the more appropriate

one of intrepidus. It is not a little remarkable that this writer, who appears to

describe the habits, &c., of this species from personal observation, should have

given (Gal. des Ois. pi. 133), as the representation of the female, the figure of

another species, which we have never seen, and certainly is not known to inhabit

North America. We rather suspect, however, that the fault must lie with the

draughtsman, who seems to have coloured this figure in such a manner as to

produce a fictitious species—the rufous wings, tail, and olive back, representing

the Tyrannus crinitus; and the white under plumage and crest being those of

intrepidus. No such species exists in the Paris museum, nor have we ever seen

Tyrannus crudelis, Sw ain s. Monog.