plumage is of a pale, colour intermediate, between oil-green and wax-yellow, the under tail

coverts approaching to ochre-yellow. Bill blackish-brown. Legs black.

Form, &c.—Bill depressed, broad, its breadth at the forehead being rather more than half

its length ; its sides are slightly convex, and meet in a straight ridge, which is terminated by

a small hooked tip. The nostrils are partly concealed by feathers and bristles, and there are

four or five stiff bristles projecting from the angles of the mouth. The tips of the wings, when

folded, are more, than an inch short of the end of the tail, and barely reach to half its length.

The third and fourth quill feathers are the longest, the second and fifth are equal to each

other, and slightly shorter than these; the sixth is a quarter of an inch shorter than the

fourth,, and. the first is intermediate in length between the sixth and seventh. The tail is

distinctly forked, the exterior feather being a quarter of an inch longer than the middle ones.

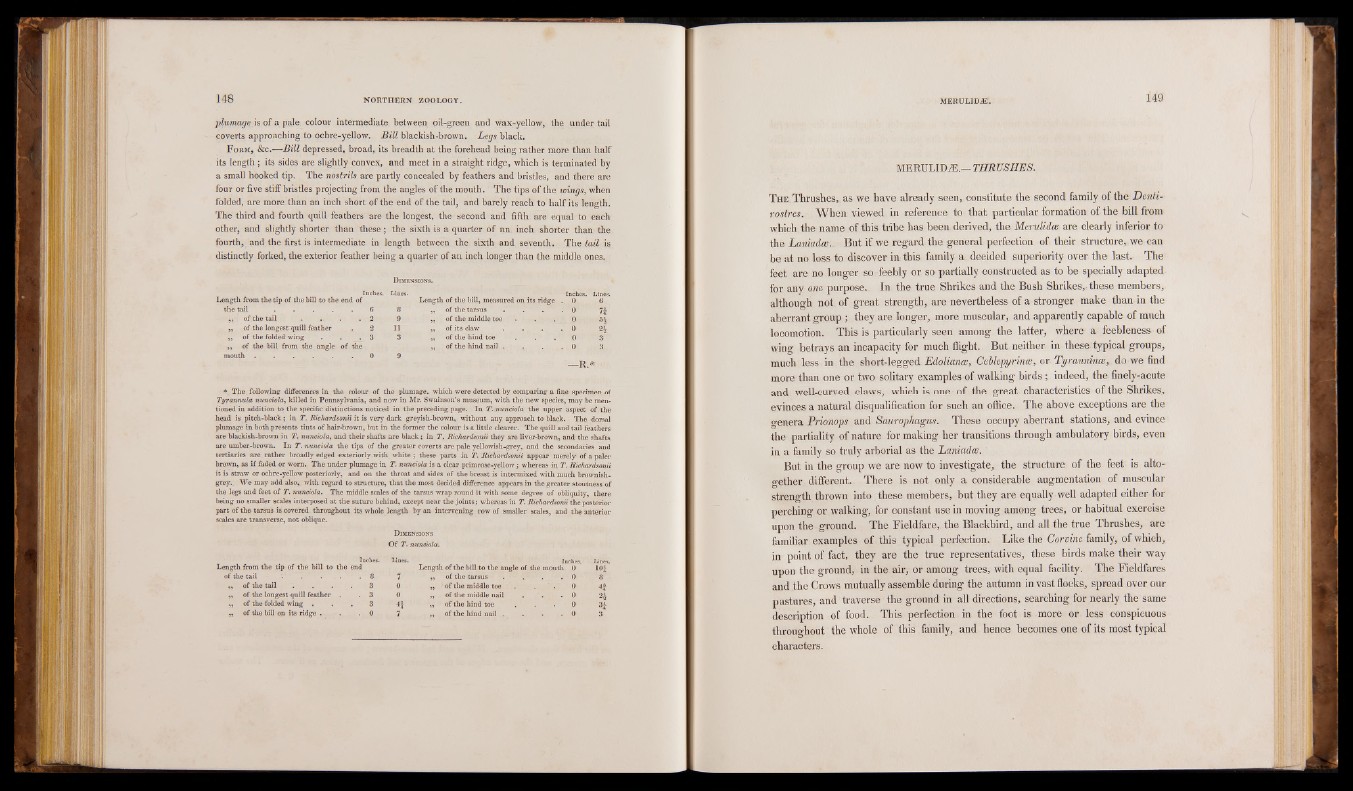

Dimensions.

Length from the tip of the bill to the end of Inches.

the tail . . . . . 6 8

Length of the bill, measured on its ridge

„ of the tarsus . . .

Inches.

•. P0

Lines;

,, of the tail. , ... 2 9 ,, of the middle toe 7i 0 „ of the longeslrquill feather 2 11 ,, of its claw . . • o 2|

H • £ of the folded wing 3 3 „ of the hind toe 0 3

,, of the bill from the angle of the

,, of the hind nail , , . 0

mouth . . . . . 0 9

— R .

3

* The following differences in the colour of the plumage, which were detected by comparing a fine specimen of

Tyrannula nuneiola, killed in Pennsylvania, and now in Mr. Swainson’s museum, with the new species, may be mentioned

in addition to the specific distinctions noticed in the preceding page. In T. nuneiola the upper aspect of the

head is pitch-black; in T. Richardsonii it is very dark greyisb-brown, without any approach to black. The dorsal

plumage in both presents tints of hair-brown, but in the former the colour is a little clearer. The quill and tail feathers

are blackish-brown in T. nuneiola, and their shafts are black; in T. Richardsonii they are liver-brown, and the shafts

are umber-brown. In T. nuneiola the tips of the greater coverts are pale yellowish-grey, and the secondaries and

tertiaries are rather broadly edged exteriorly-with white; these parts in T, Richardsonii appear merely of a paler

brown, as if faded or worn. The under plumage in T. nuneiola is a clear primrose-yellow; whereas in T. Richardsonii

it is straw or ochre-yellow posteriorly, and on the throat and sides of the breast is intermixed with much brownish-

grey.. We may add also, with regard to structure, that the most decided difference appears in the greater stoutness of

the legs and feet of T. nuneiola. The middle scales of the tarsus wrap round it with some degree of obliquity, there

being no smaller scales interposed at the suture behind, except near the joints; whereas in T. Richardsonii the posterior

part of the tarsus is covered throughout its whole length by an intervening row of smaller scales, and the anterior

scales are transverse, not oblique.

Dimensions

Of T. nuneiola.

Length from the tip of the bill to the endInches. Lines. Length of the bill to the angle of the mouthI nch0es. .'Lines 10i

of the tail *. . . a 7 ■ „ of the tarsus . ., . 0 8

of the tail 3 0 „ ■ of the middle toe . . ‘ . 0 4f ,, of the longest quill feather . . 3 0 ,, . of the middle nail . . . 0 2£

,, of the folded wing . . 3 4* „ of the hind toe 0 3*

,, of the bill on its ridge . . 0 7 ,, of the hind nail . . . . 0 3

MERULIDjE.— THRUSHES.

The Thrushes,, as we have already seen, constitute the second family of the Denti-

rostres. When viewed in reference to that particular formation of the bill from

which the name of this tribe has been derived, the Merulidte are clearly inferior to

the Laniadw.. But if we regard the general perfection of their structure, we can

be at no loss to discover in this family a. decided superiority over the last.- The

feet are no longer so feebly or so partially constructed as to be specially adapted

for any one purpose- In the true Shrikes and the Bush Shrikes, these members,

although not of great strength, are nevertheless of a stronger make than in the

aberrant group ; they are longer, more muscular, and apparently capable of much

locomotion. This is particularly seen among the latter, where a feebleness of

wing betrays an incapacity for much flight. But neither in these, typical groups,

much less in the short-legged Edolianai, Ceblepyrinte, or Tyrannince, do we find

more than one or two solitary examples of walking birds; indeed, the finely-acute

and well-curved claws, which is one of the great characteristics of the Shrikes,

evinces a natural disqualification for such an office. The above exceptions are the

genera Prionops and Saurophagus. These occupy aberrant stations, and evince

the partiality of nature for making her transitions through ambulatory birds, even

in a family so truly arborial as the Laniadce. But in the group we are now to investigate, the structure of the feet is altogether

different. There is not only a considerable augmentation of muscular

strength thrown into these members, but they are equally well adapted either for

perching or walking, for constant use in moving among trees, or habitual exercise

upon the ground. The Fieldfare, the Blackbird, and all the true Thrushes, are

familiar examples of this typical perfection. Like the Corvine family, of which,

in point of fact, they are the true representatives, these birds make their way

upon the ground, in the air, or among trees, with equal facility. The Fieldfares

and the Crows mutually assemble during the autumn in vast flocks, spread over our

pastures, and traverse the ground in all directions, searching for nearly the same

description of food. This perfection in the foot is more or less conspicuous

throughout the whole of this family, and hence becomes one of its most typical

characters.