for first we were aroused by “ the watchmen that go

about the city,” who had some dull imitation of a gong

or bell wherewith to make us aware of their presence,

and then there came into our principal court a howling

cur, “ returned at evening to make a noise like a dog, and

go round about the city.” * I sallied forth with a lighted

candle, and drove out the dog, but was afraid of going

too far in my queer déshabille, lest, being unable, if

discovered, to give an account of myself in the vernacular,

I might cause the natives to wonder what in

the world I was about. The rules concerning keeping

at home after sunset are very strict, and the night

myrmidons in the pay of the Mir-sheb, or chief police-

master (called Kurbashi in Samarkand), think little of

dealing summarily with anyone found in the streets,t

so much so that one of the Russians who had paid us an

evening visit, and who left quite early, did not like to

pfo home without one of the Emir’s attendants to accom-

pany him. Then, again, early next morning we were

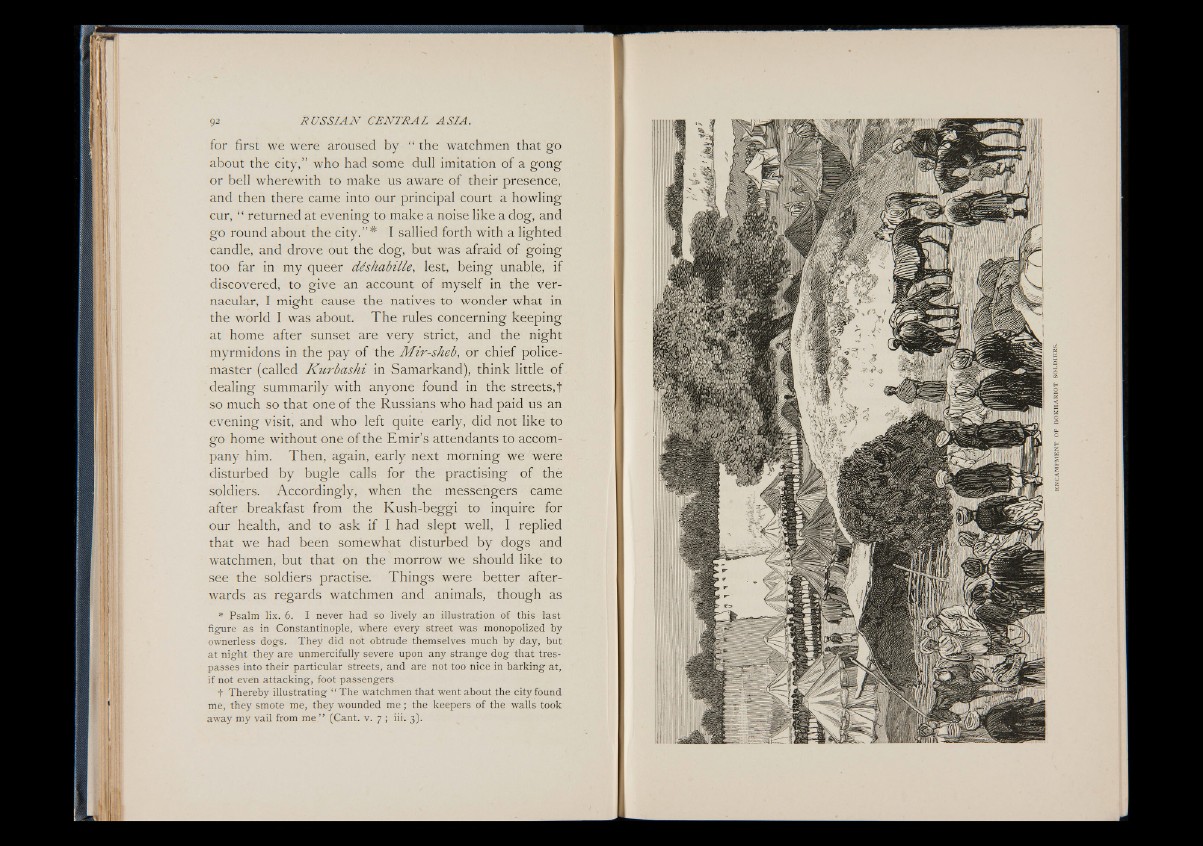

disturbed by bugle calls for the practising of thè

soldiers. Accordingly, when the messengers came

after breakfast from the Kush-beggi to inquire for

our health, and to ask if I had slept well, I replied

that we had been somewhat disturbed by dogs and

watchmen, but that on the morrow we should like to

see the soldiers practise. Things were better afterwards

as regards watchmen and animals, though as

* Psalm lix. 6. I never had so lively an illustration of this last

figure as in Constantinople, where every street was monopolized by

ownerless dogs. They did not obtrude themselves much by day, but

at night they are unmercifully severe upon any strange dog that trespasses

into their particular streets, and are not too nice in barking at,

if not even attacking, foot passengers

f Thereby illustrating “ The watchmen that went about the city found

me, they smote me, they wounded me ; the keepers of the walls took

away my vail from me ” (Cant. v. 7 ; iii. 3).