are 22 of the former and 17 of the latter. My notes

say “ 4 large medresses and many small.” The

medresse of Allah-Kuli was built by the present Khan’s

father, about 40 years ago. It is o f 2 stories, and has

100 students, they said. That of Kutlug Murad Inag

has about 100 students. On the square, before the

Khan’s winter palace, is the Medresse Madrahim, built

by the present Khan, with from 60 to 70 students only.

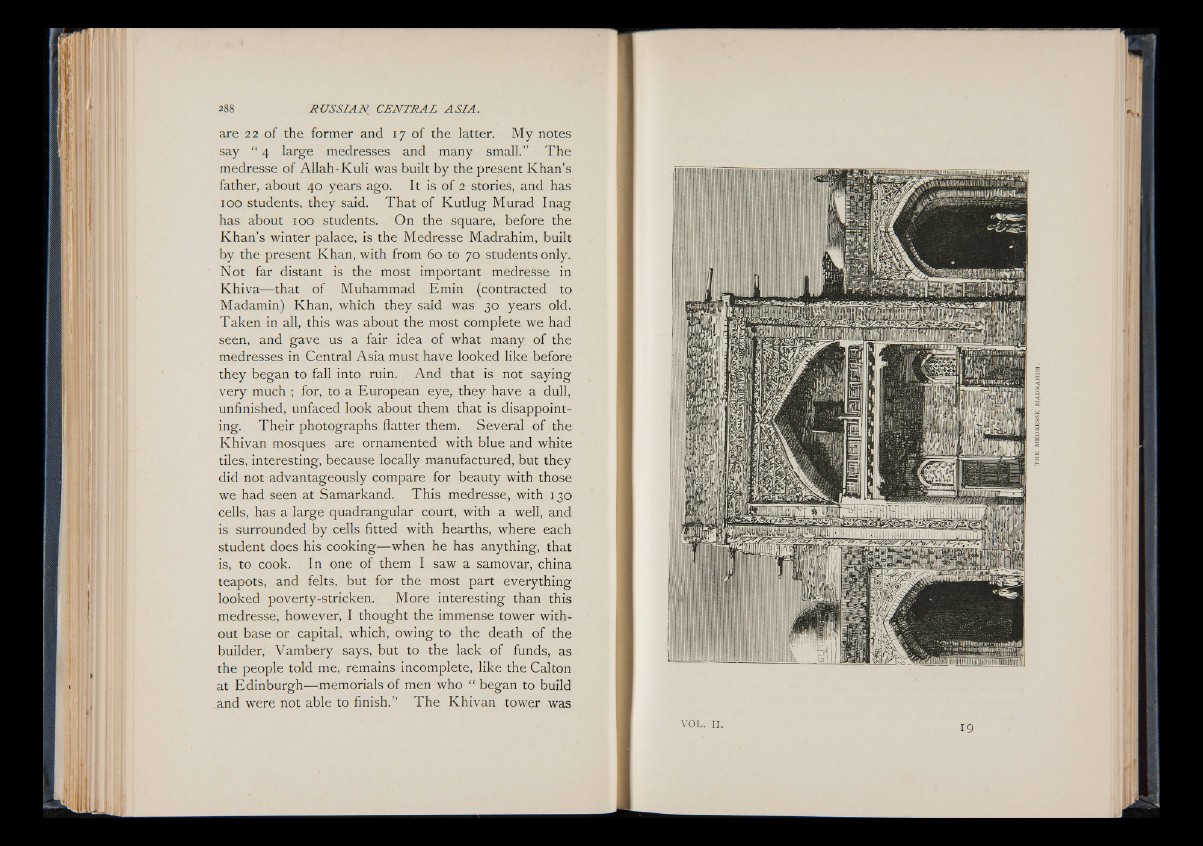

Not far distant is the most important medresse in

Khiva— that of Muhammad Emin (contracted to

Madamin) Khan, which they said was 30 years old.

Taken in all, this was about the most complete we had

seen, and gave us a fair idea of what many of the

medresses in Central Asia must have looked like before

they began to fall into ruin. And that is not saying

very much ; for, to a European eye, they have a dull,

unfinished, unfaced look about them that is disappointing.

Their photographs flatter them. Several of the

Khivan mosques are ornamented with blue and white

tiles, interesting, because locally manufactured, but they

did not advantageously compare for beauty with those

we had seen at Samarkand. This medresse, with 130

cells, has a large quadrangular court, with a well, and

is surrounded by cells fitted with hearths, where each

student does his cooking— when he has anything, that

is, to cook. In one of them I saw a samovar, china

teapots, and felts, but for the most part everything

looked poverty-stricken. More interesting than this

medresse, however, I thought the immense tower without

base or capital, which, owing to the death of the

builder, Vambery says, but to the lack o f funds, as

the people told me, remains incomplete, like the Calton

at Edinburgh— memorials of men who “ began to build

and were not able to finish.” The Khivan tower was

VOL. 11