all over, but without a stick of furniture, except two

roughly-made deal chairs with crimson seats. The

Emir was perched on one, and, after giving me a feeble

shake of the hand, he motioned me to the other. I

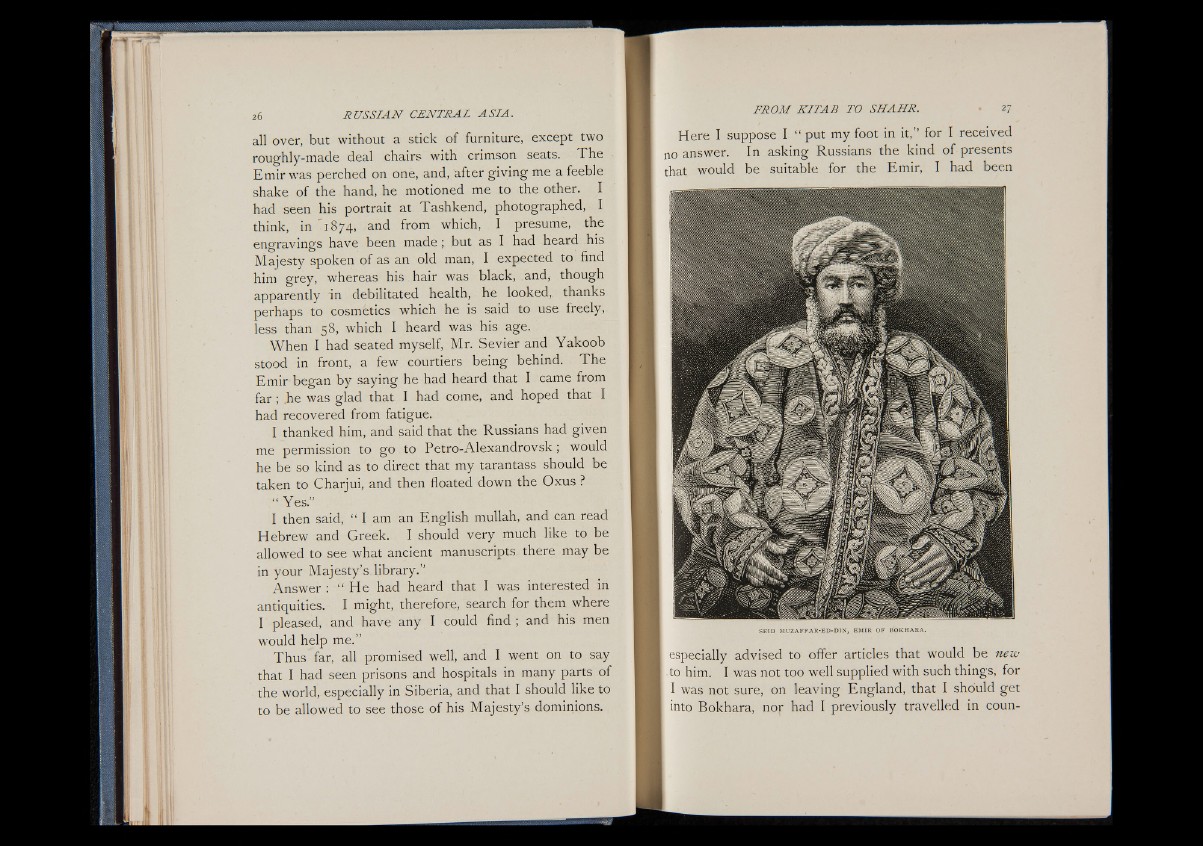

had seen his portrait at Tashkend, photographed, I

think, in ’ 1874, and from which, I presume, the

engravings have been made; but as I had heard his

Majesty spoken of as an old man, I expected to find

him grey, whereas his hair was black, and, though

apparently in debilitated health, he looked, thanks

perhaps to cosmetics which he is said to use freely,

less than 58, which I heard was his age.

When I had seated myself, Mr. Sevier and Yakoob

stood in front, a few courtiers being behind. The

Emir began by saying he had heard that I came from

fa r ; .he was glad that I had come, and hoped that I

had recovered from fatigue.

I thanked him, and said that the Russians had given

me permission to go to Petro-Alexandrovsk ; would

he be so kind as to direct that my tarantass should be

taken to Charjui, and then floated down the Oxus ?

“ Yes.” ,

I then said, “ I am an English mullah, and can read

Hebrew and Greek. I should very much like to be

allowed to see what ancient manuscripts there may be

in your Majesty's library.”

Answer : “ He had heard that I was interested in

antiquities. I might, therefore, search for them where

I pleased, and have any I could find ; and his men

would help me.”

Thus far, all promised well, and I went on to say

that I had seen prisons and hospitals in many parts of

the world, especially in Siberia, and that I should like to

to be allowed to see those of his Majesty’s dominions.

Here I suppose I “ put my foot in it,” for I received

no answer. In asking Russians the kind of presents

that would be suitable for the Emir, I had been

SKID MU ZAF FAR -ED-DIN, EMIR OF BOKHARA.

especially advised to offer articles that would be new

■ to him. I was not too well supplied with such things, for

I was not sure, on leaving England, that I should get

into Bokhara, nor had I previously travelled in coun