the harness was forthcoming, no one appeared to know

how to put it on, and this business took so long that

we were not out of the city till nearly 8 o’clock.

In the suburbs we crossed a long bridge of nine

brick arches, spanning the Kashka-daria, and had not

got far when messengers came galloping after us,

saying that the Bek had only just heard from the

Emir that he was to give for myself and Sevier the

presents they were now bringing. The gift consisted

of pieces of silk and velvet of native manufacture, the

latter remarkable by reason of their variegated colours

and patterns. Sevier and I decided to ride the first

stage, which was pleasant enough, for the road passed

through the continuously inhabited district of the

Karshi oasis. A t first we kept beside the carriage,

behind our own attendants and a cavalcade that

escorted us from Karshi, but I soon became disgusted

at our slow pace. The postilions seemed to have no

notion, of putting the horses at a respectable trot, and

I foresaw that we should be a long time getting to

Bokhara, unless I urged them on. Precept seemed to

have no effect, so I determined to try the force of

example ; and, setting at nought their notions of propriety

that I should ride in state behind, I told one of

the djiguitts to keep with the carriage whilst I galloped

on and left them to follow, and thus we reached Kassan.*

Kassan is a large commercial village, situated at the

extreme western point of the oasis. Beyond Kassan

the steppe begins, with vegetation, however, and kish-

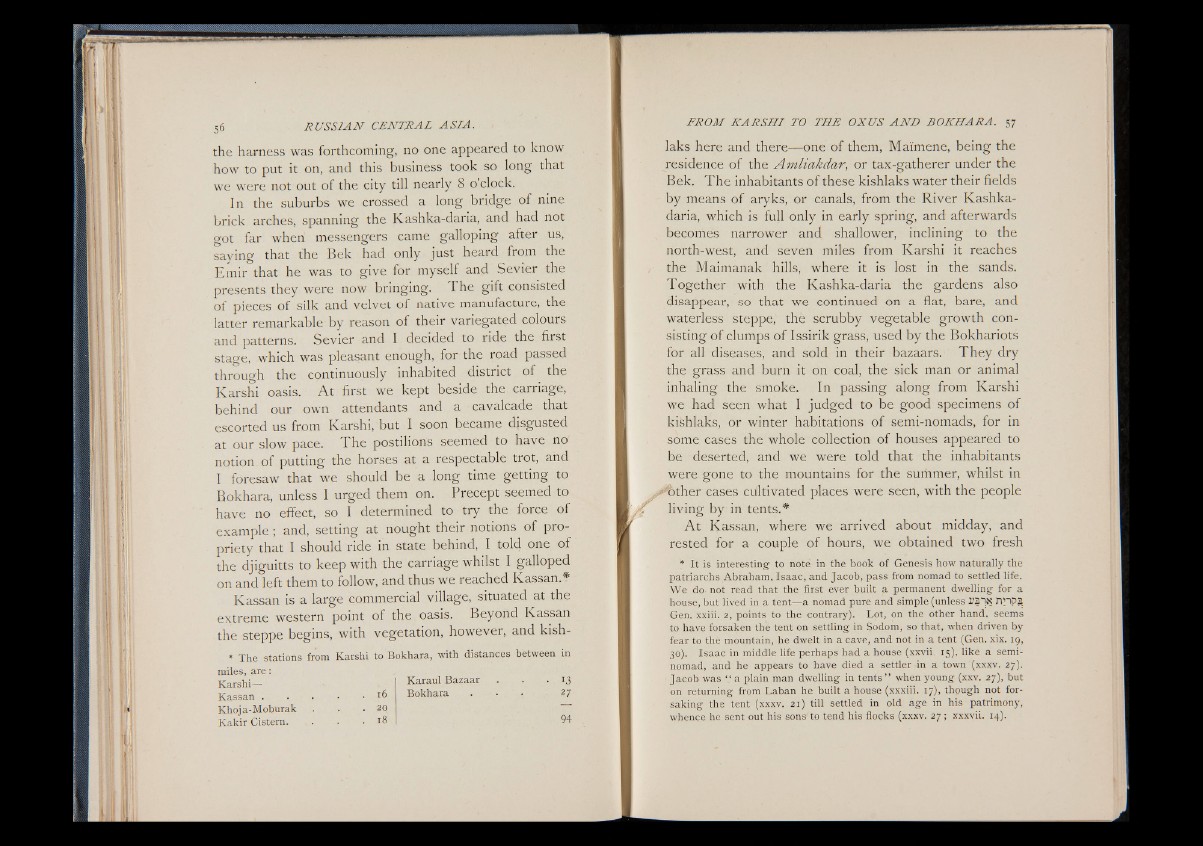

* The stations from Karshi to Bokhara, with distances between in

miles, are:

Karshi—

Karaul Bazaar . . . 13

Kassan . . . . • 16

Bokhara . . . 2 7

Khoja-Moburak . . . 2 0

Kakir Cistern. . . . 18-

94

laks here and there— one of them, Maimene, being the

residence of the Amliakdar, or tax-gatherer under the

Bek. The inhabitants of these kishlaks water their fields

by means of aryks, or canals, from the River Kashka-

daria, which is full only in early spring, and afterwards

becomes narrower and shallower, inclining to the

north-west, and seven miles from Karshi it reaches

the Maimanak hills, where it is lost in the sands.

Together with the Kashka-daria the gardens also

disappear, so that we continued on a flat, bare, and

waterless steppe, thè scrubby vegetable growth consisting

of clumps of Issirik grass, used by the Bokhariots

for all diseases, and sold in their bazaars. T hey dry

the grass and burn it on coal, the sick man or animal

inhaling the smoke. In passing along from Karshi

we had seen what I judged to be good specimens of

kishlaks, or winter habitations of semi-nomads, for in

some cases the whole collection of houses appeared to

be deserted, and we were told that the inhabitants

were gone to the mountains for the summer, whilst in

Either cases cultivated places were seen, with the people

living by in tents.*

A t Kassan, where we arrived about midday, and

rested for a couple of hours, we obtained two fresh

* It is interesting to note in the book of Genesis how naturally the

patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, pass from nomad to settled life.

We do, not read that the first ever built a permanent dwelling for a

house, but lived in a tent—a nomad pure and simple (unless JVTp2

Gen. xxiii. 2, points to the contrary). Lot, on the other hand, seems

to have forsaken the tent on settling in Sodom, so that, when driven by

fear to thè mountain, he dwelt in a cave, and not in a tent (Gen. xix. 19,

30). Isaac in middle life perhaps had a house (xxvii. 15), like a seminomad,

and he appears to have died a settler in a town (xxxv. 27).

Jacob was a plain man dwelling in tents ” when young (xxv. 27), but

on returning from Laban he built a house (xxxiii. 17), though not forsaking

the tent (xxxv. 21) till settled in old age in his patrimony,

whence he sent out his sons'to tend his flocks (xxxv. 27 ; xxxvii. 14).