questioning as I think the natives had not often

experienced before.

On our last afternoon in Khiva we went to pay the

customary farewell visit to the Khan. He received

us as before, and seemed rather inclined to talk politics,

which, however, is not my forte. He had heard of

our war going on in Egypt, and asked whether the

affair were cleared up. I had supposed that this war

with Muhammadans might have rendered it unsafe for

us to travel in Central Asia, but the people seemed to

know next to nothing about it, and to care as little. I

had heard no news since leaving Samarkand, and not

much there, so that I was obliged to explain the situation

as best I could. His Highness asked my name

and (following in the same interrogative groove as the

Bek in Bokhara) my age, and inquired if we had been

well entertained in Khiva. This we were able to

answer truly in the affirmative, thanks to the hospitality

of his Divan-beggi. Before bidding us farewell, he

said that he had directed Matmurad to give us men

to take our baggage, and that he had also sent to

seek for a Russian-speaking djiguitt to accompany us

to Krasnovodsk.

Yakoob, who took up his habitation with the servants,

and who had not told them that he spoke Tajik as

well as Turki, rather amused us that evening by telling

us that there had been a discussion going on outside

as to whether it would be proper to give us presents

from the Khan. It was at length decided in the affirmative,

and there came a horse and cloth khalat for me,

a similar khalat for Sevier, and a cotton one for Yakoob.

Captain Burnaby was informed, he says, that “ a khalat

or dressing-gown from the Khan is looked upon at

Khiva much as the Order of the Garter would be in

England,” at which rate I suppose that I, who had

received them in Bokhara by dozens, ought to consider

myself “ very much knighted.”

This honour Tailly seemed anxious also to share, for

he cunningly left with Yakoob a limited number of

roubles to be offered for the two cloth khalats, telling

Yakoob that he wished to take them back to Petro-

Alexandrovsk, and there to cut a dash, representing

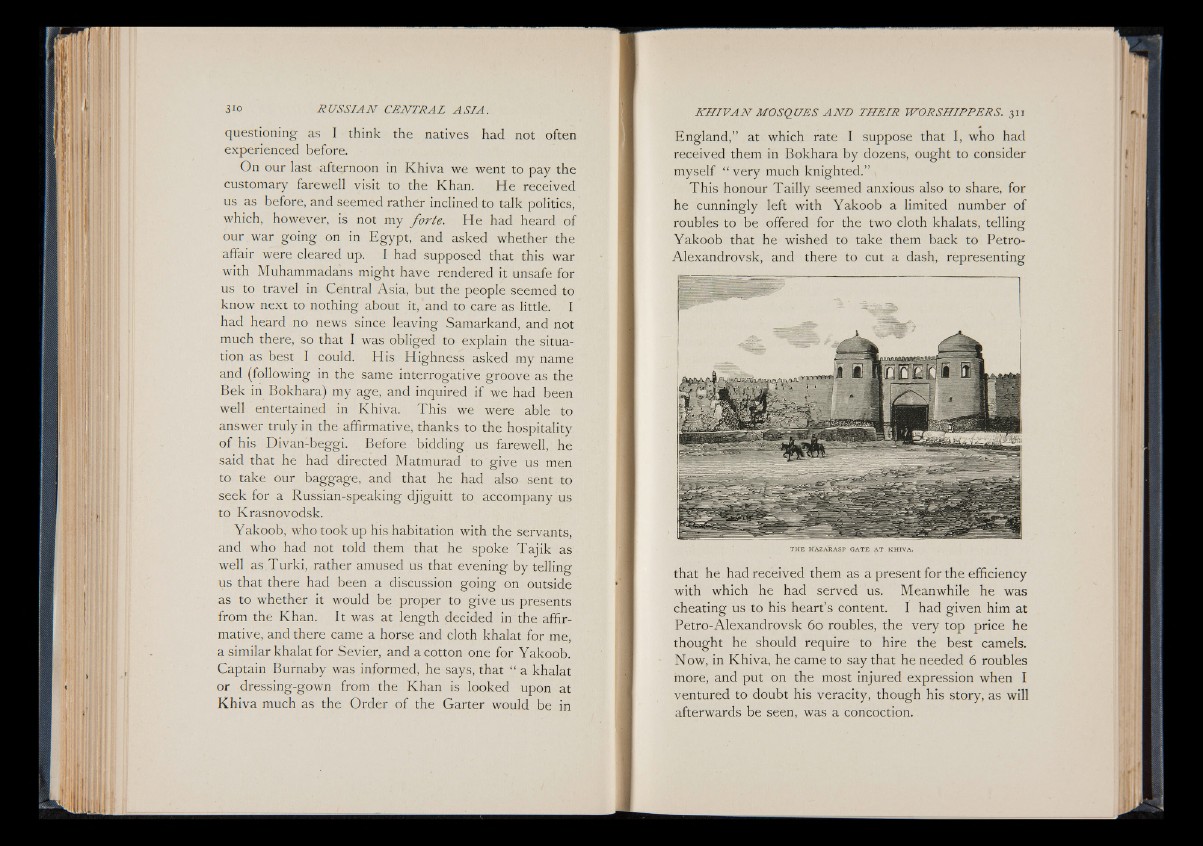

TH E HAZARASP G A T E A T KH IVA.

that he had received them as a present for the efficiency

with which he had served us. Meanwhile he was

cheating us to his heart’s content. I had given him at

Petro-Alexandrovsk 60 roubles, the very top price he

thought he should require to hire the best camels.

Now, in Khiva, he came to say that he needed 6 roubles

more, and put on the most injured expression when I

ventured to doubt his veracity, though his story, as will

afterwards be seen, was a concoction.