properly so termed personal pronoun of the Î,third person çor-

responding to lie, she, it, and use demonstratives instead of

it ; but the terminations of verbs in the third person singular

shew plainly what the personal pronoun must have been.

This form, ends in at, et, ti, See. ; and we ; find that the

pronoun is thus suffixed in general, and is also an article.

The same phenomenon appears, according to M. Bopp, in

many of the Malayo-Polynesian languages : te, ho, &e. are

used both as articles and as suffix pronouns connected yvith

verbs-denoting the third person.

The Sanskrit relative y a has some analogies,, according to

Bopp, in the insular languages. Y an is the definite article,

and is used for a relative pronoun in Malay, In Tagala we

find yaon, ille, and in Bugis yatu ; îtu, Malay ; ito, Tagala,

probably compounded of ya and to. With the Sanskrit de-j

monstrative esa or eska, the Maleoassian isa corresponds. |

These instances of rësemblance which I have cited in the

pronouns and numerals of the Sanskrit and the Malayo-Pt^y-

nesian languages are certainly remarkable. The resemblances

iji the ordinary vocabularies of the two clashes of languages

are not so frequent as might be inferred from what has been

sàidl M. Bopp' has, however, jdhewn that $. considerable

number of analogies may be found in the roots of verbs, The

following instances of resemblance in nouns were seisctpd by

M. Buschmann, and were given i n p n e o f •his/notea to

Humboldt’s work on the Kawi-Sprache.#

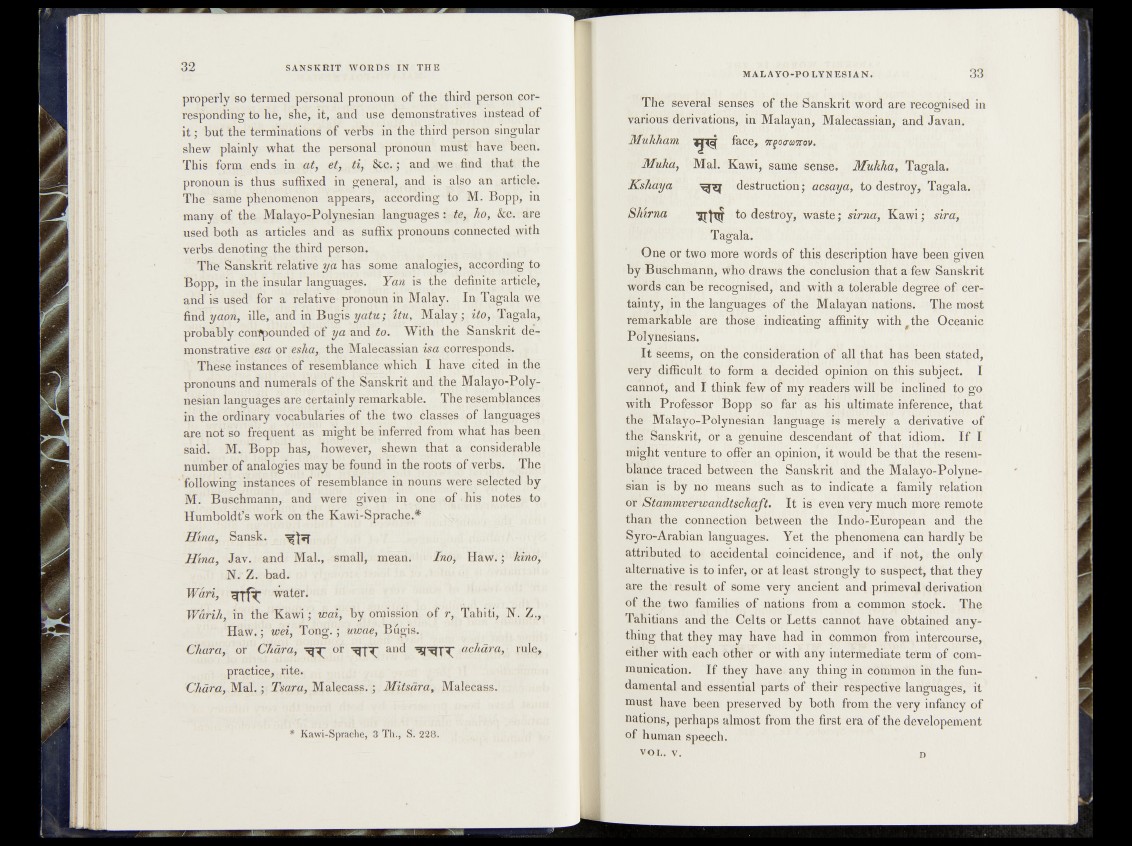

Hina, Sansk. r

Hina, Jav. and Mai., small, mean. Inof Haw. ; kino,

N. Z. bad.

Warn, water.

Wârih, in the Kawi ; wax, by omission of r, Tahiti, K. Z.,

Haw.; wet, Tong; uwae, Bugis.

Chara, or Ctiâra, or and achàrq,; rule,

j practice, rite.

Chàra,*Mal. ; Tsara, Malecass. ; Mitsâra, Maleeass.

* Kawi-Sprache, 3 Th., S. 228.

The several senses of the Sanskrit word are recognised in

various derivations, in Malayan, Malecassian, and Javan.

Muhham face, wfotrumv,

Muka, Mai. Kawi, same sense. Mukha, Tagala.

Kshaya destruction; acsaya, to destroy, Tagala.

SMrna to destroy, waste; sirna, Kawi; sira,

Tagala.

One or two more words of this description have been given

by Buschmann, who draws the conclusion that a few Sanskrit

words can be recognised, and with a tolerable degree of certainty,

in the languages of the Malayan nations. The most

remarkable are those indicating affinity with the Oceanic

Polynesians.

It sbems, oh the consideration of all that has been stated,

very difficult to form a decided opinion on this subject. I

cannot, and I think few of my readers will be inclined to go

with Professor Bopp so far as his ultimate inference, that

the Malayo-Polynesian language is merely a derivative of

th&'Sanskrit, or a genuine descendant of that idiom. If I

might venthre to offer an. opinion, it would be that theresetm

blance traced between the Sanskrit and the Malayo-Polynesian

is by no means such as to indicate a family relation

ot Siammverwandtschaft. It is even very much more remote

than the connection between the Indo-European and the

Syro-Arabian languages. Yet the phenomena can hardly be

attributed'; to accidental coincidence, and ifii not, the only

alternative is to infer, or at least strongly to suspect* that they

are the‘result of some very ancient and primeval derivation

of the two families of nations from a common stock. The

Tahitians and the Celts or Letts cannot have obtained anything

that they may have had in common fromxintercourse,

either with each other or with any intermediate term of communication.

If they have, any thing in common ih the fundamental

and essential parts of their respective languages, it

must have been preserved by both from the very infancy of

nations, perhaps almost from the first era of the developement

of human speech.

vo l. j v. D