4t The definite article' is a, as a liga, ‘ the hand’. It forms th®

plural by adding log a, which is probably cognate with the Tonga loa,

meaning- ‘ large’, ‘ extensive’, as a Mg a- l i g ‘ the hands’. This

addition is analogous to man, which forms the plural in the, Tahitian.

Unlike the habit of ^h^ 'JE^pte^t^idia^cts, the a bocomesj na after

a proposition, as i-na-liga, ‘ in the hand’. _ Still more curious is the

fact that- some nouns produce a change in the preceding word,

causing it to end in i if it be an article or pronoun. Thus, ‘ the staff’

is a i jitoko, for d jUokffi—t^ ^ o a logoipuli, for a log a

ptiifoyBB in their purses’, i na odrai oro, for odra oro.

“ The adjectives follow the substantives in all these idioms,

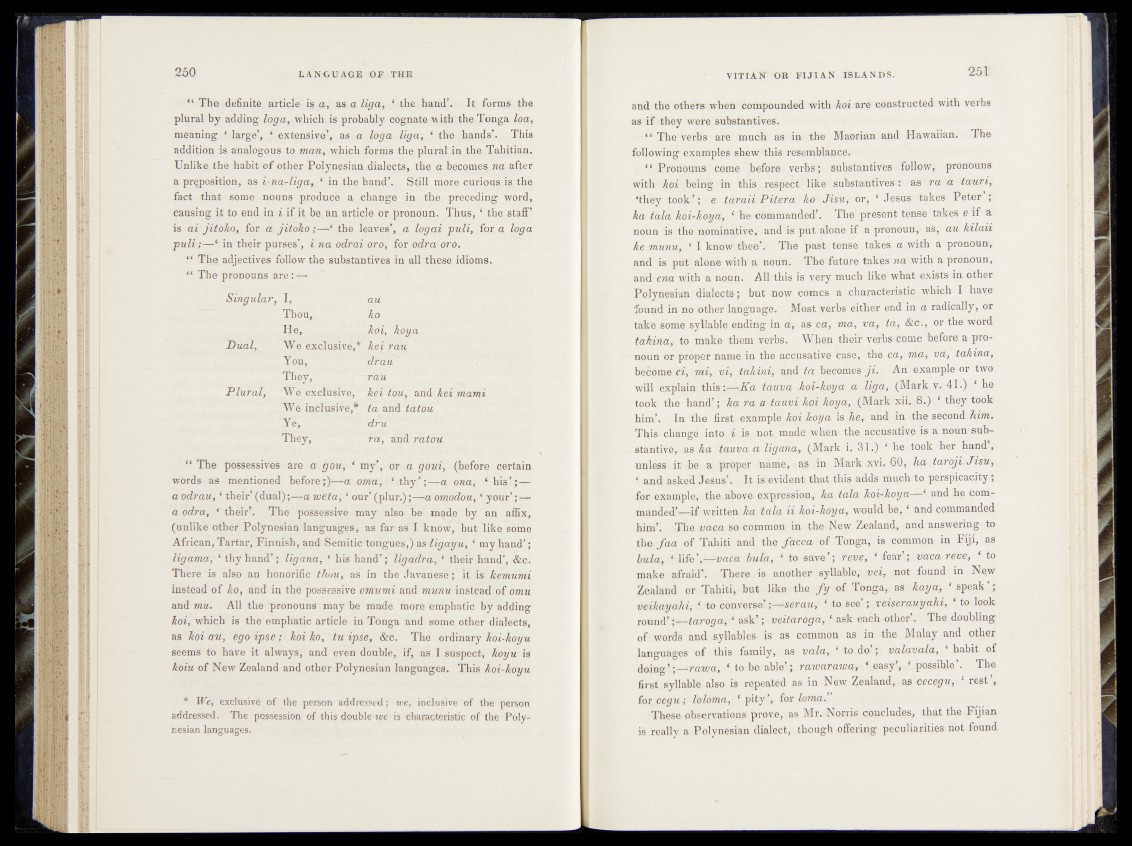

“ The pronouns are:

Singular, I,

Thou,

He,

Dual, We exclusive",*

You,

They5,

Plural, We exclusive,"

_We inclusive,*

Ye,

They,

au

ko

koi, koya

ke\ pau

drau

~TC£U

kei tou, and kei mami

ta and tctfoit ;

dru

ra, and ratari

“ The possessives are a gou, * my’, or a gout, (before certain

words as. mentioned before;)—a oma, i ‘ thy’;—a ona, & bi&’;—

a odrau, ‘ their’ (dual);-—a weta, ‘ our’ (plur.);-»-a omodou, ‘ your’;-—

a odra, f their’. The possessive may also be m^de by an affix,

(unlike other Polynesian languages, as far as I know, but like some

African, Tartar, Finnish, and Semitic tongues,) as lig ay u, ‘ my hand’;

ligatna, | thy hand’; ligana, ‘ his hand’; ligadra, ‘ their hand’, &c.

There is also an honorific thou, as in the Javanese; i l ls kemumi

instead of ko, and in the possessive orhumi and munu instead of omu

and mu. All the pronouns -may be made more emphatic by adding

koi, which is the emphatic article in Tonga and some other dialects,

as koiau, ego ipse; koi ko, tu ipse, &c. The ordinary koi-koyu

seems to have it always, and even double, if, as I suspect, koyu is

koiu of New Zealand and other Polynesian languages. This koi-koyu

* We, exclusive of the person addressed; we, inclusive of the person

addressed. The possession, of this double we is characteristic of the Polynesian

languages;

and the others when compounded with koi are constructed with verbs

as if they were substantives.

The1 verbs are much as in the Maorian and Hawaiian. The

following examples, shew this resemblance. •'$»

“ Pronouns Cpme : before yerbs; substantives follow, pronouns

with koi being in this^ respect like Substantives: as ra a ia u r i,

‘they took’; e- ta ra ii P ife r a - ko ,Jisu'j1 or, ‘ Jesus takes Peter ;

ka ialtu-koi-koya, \\he commanded’. The present'tense takes e if a

noun is the nominative, and is1 put alone if a pronoun,- as, au k ila ii

ke munu, ‘ I know1 thee’. The past tense takes a with a pronoun,

and is put alone with a noun. The future takes na with a pronoun,

and ena with a noun. All this is very much like1 tvhat exists in other

Polynesian dialects; but now comes a characteristic which I have

found in no other language. Most verbs either^ end in a radically, or

take some syllable ending in a^; as ca, ma, vg , , ta , &c&/'or the word

takina, to make them verbs. When their verbs come before a pro-

1 noun erpropef name in the accusative base, the ca, ma^ takina,

he’come d, ■ dethmir '’dad ta becomes ji.^ An'example or two

will explain this^r-dYa tauvaikoi-kjaya h’tjca, (Mark v. 41.) ‘ he

took the hand’; ka ra a tau v i koi fypya, ^Mark xii. 8*) ‘ they'took

him’. j j4n the first example koi koya is he, and in 'the second him.

This change into i is not made when the accusative is a noun substantive,

as ka tauva a ligana, (Mark i. he took her hand,

unless it be a proper name, as .in Mark xvi. JIQ, ha targjv J isu ,

1 and askeff,Jesus;’. It is.evide»t,tbat this, adds much to perspicacity,;

fot example, the above expression, ka ta la koi-.koya—-h and he commanded’—

if written ka ta la ii koi-koya, would .be, ‘ and commanded

him’. The vaqa so common in the New Zealand, .and answering to

the f a a of Tahiti and the fa c c a of Tonga, is common in Fiji, as

bula, \M$i’,-rruam bula, ‘ to save’; rpv^ h'io^t’i^vaca reve, ‘ to

make afraid’. There is another syllable, not found in New

Zealand or Tahiti, hut like the f y of Tonga, as % a , ‘ speak.’;

veikayahi, ‘ to converse’ ;-^serau, ‘ to. see’ ueiserauyahi, ftp look-

round’ ;— tarogai ‘ ask’; veitaroga, f ask each, other’-.^ The doubling

of words and syllables is as common as in the Malay and other

languages of this family, as va la , ‘ to do’;< va la va la , ‘ habit of

doing’;—return, \ to he able’; remarawa, Apasy^ ‘ possible.’- The

first syllable also is repeated as in New Zealand, as cecegu, * rest’,

foucegu; loloma, ‘ pity’, for loma.” ^ ;.vf^:v.

These observations prove, as Mr. Norris concludes, that the Fijian

is really a Polynesian dialect, though offering peculiarities not found