charged with sago starch passes on to a trough, with a

depression in the centre, where the sediment is deposited,

the surplus water trickling off by a shallow outlet. When

the trough is nearly full, the mass of starch, which has a

slight reddish tinge, is made into cylinders of about thirty

pounds’ weight, and neatly covered with sago leaves, and

in this state is sold as raw sago.

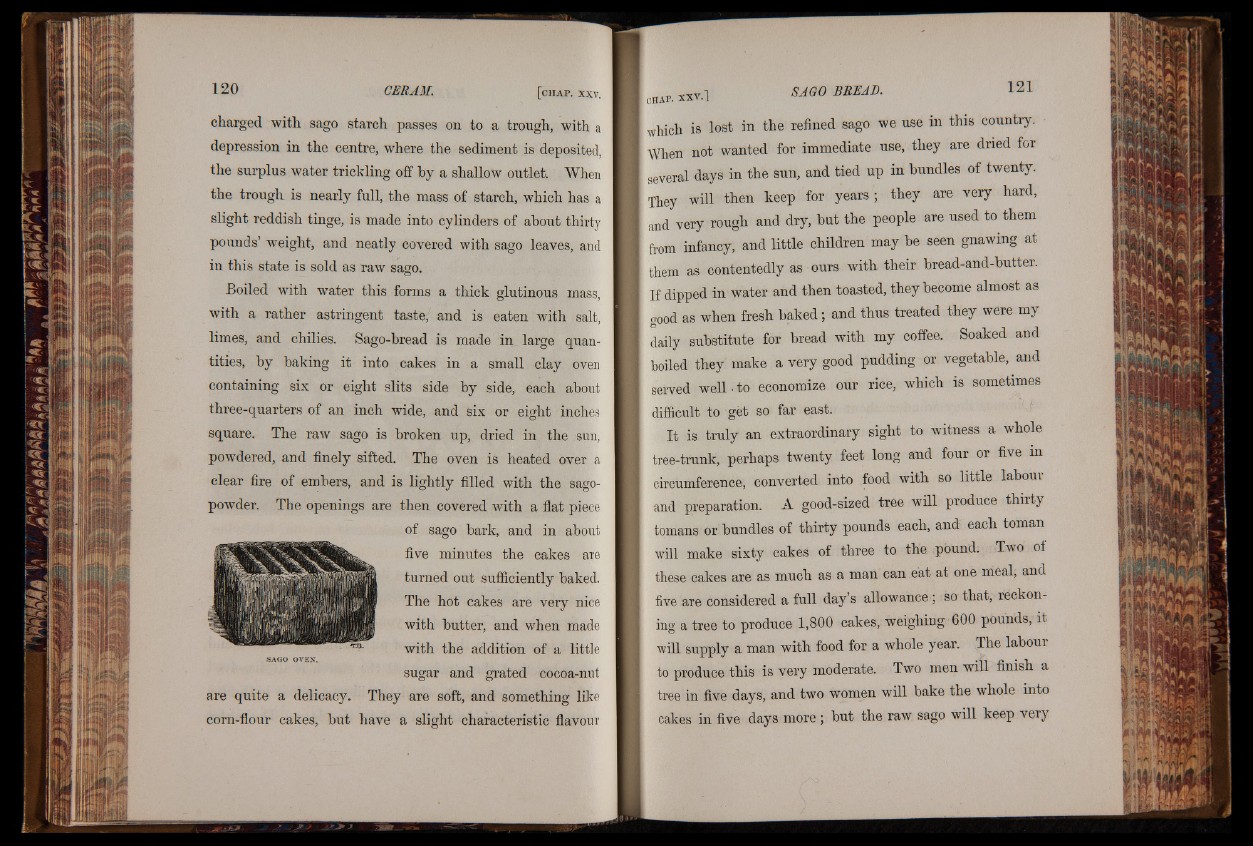

Boiled with water this forms a thick glutinous mass,

with a rather astringent taste, and is eaten with salt,

limes, and chilies. Sago-bread is made in large quantities,

by baking it into cakes in a small clay oven

containing six or eight slits side by side, each about

three-quarters of an inch wide, and six or eight inches

square. The raw sago is broken up, dried in the sun,

powdered, and finely sifted. The oven is heated over a

clear fire of embers, and is lightly filled with the sago-

powder. The openings are then covered with a flat piece

of sago bark, and in about

five minutes the cakes are

turned out sufficiently baked.

The hot cakes are very nice

with butter, and when made

with the addition of a little

sugar and grated cocoa-nut

are quite a delicacy. They are soft, and something like

corn-flour cakes, but have a slight characteristic flavour

which is lost in the refined sago we use in this country.

When not wanted for immediate use, they are dried for

several days in the sun, and tied up in bundles of twenty.

They will then keep for years ; they are very hard,

and very rough and dry, but the people are used to them

from infancy, and little children may be seen gnawing at

them as contentedly as ours with their bread-and-butter.

If dipped in water and then toasted, they become almost as

good as when fresh baked; and thus treated they were my

daily substitute for bread with my coffee. Soaked and

boiled they make a very good pudding or vegetable, and

served well • to economize our rice, which is sometimes

difficult to get so far east.

It is truly an extraordinary sight to witness a whole

tree-trank, perhaps twenty feet long and four or five in

circumference, converted into food with so little labour

and preparation. A good-sized tree will produce thirty

tomans or bundles of thirty pounds each, and each toman

will make sixty cakes of three to the pound. Two of

these cakes are as much as a man can eat at one meal, and

five are considered a full day’s allowance ; so that, reckoning

a tree to produce 1,800 c a k e s , weighing 600 pounds, it

will supply a man with food for a whole year. The labour

to produce this is very moderate. Two men will finish a

tree in five days, and two women will bake the whole into

cakes in five days more ; but the raw sago will keep very