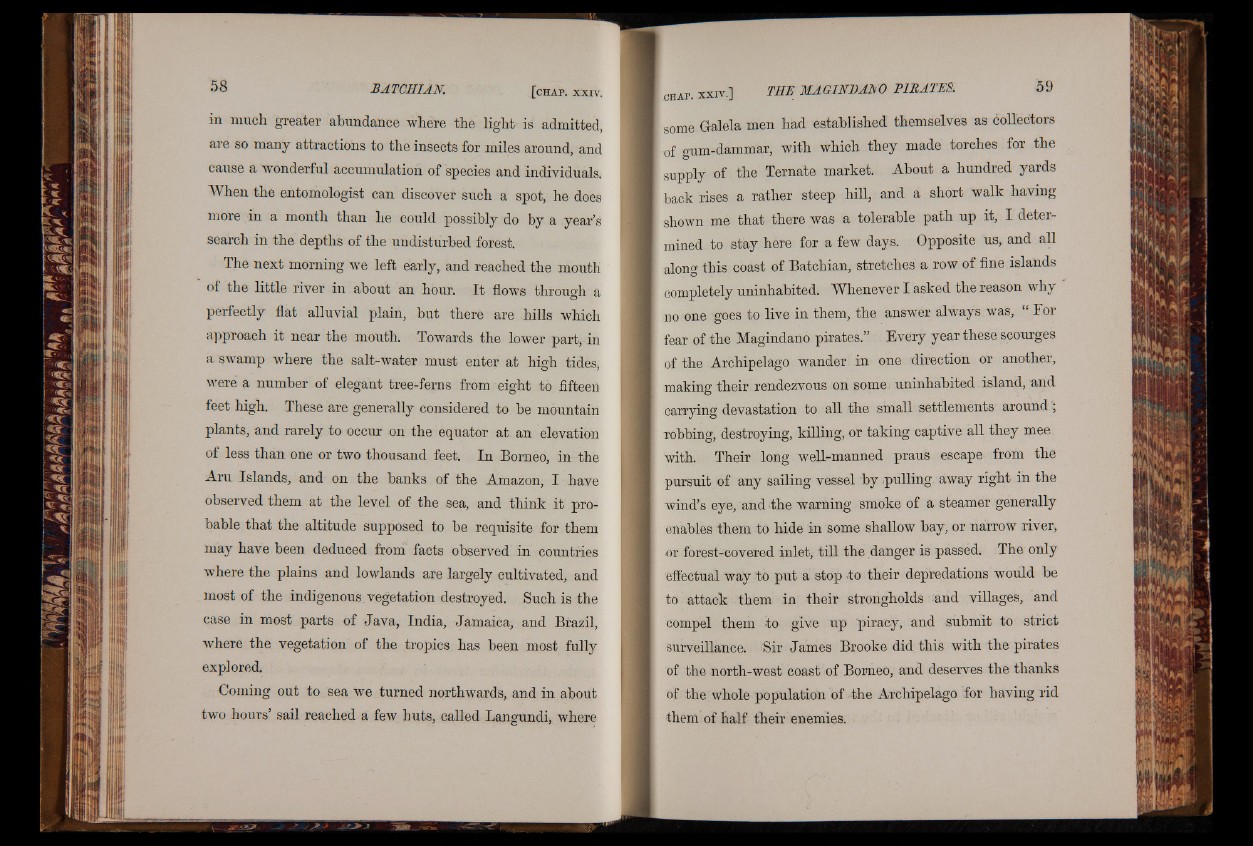

in much greater abundance where the light- is admitted,

are so many attractions to the insects for miles around, and

cause a wonderful accumulation of species and individuals.

When the entomologist can discover such a spot, he does

more in a month than he could possibly do by a year’s

search in the depths of the undisturbed forest.

The next morning we left early, and reached the mouth

of the little river in about an hour. It flows through a

perfectly flat alluvial plain, but there are hills which

approach it near the mouth. Towards the lower part, in

a swamp where the salt-water must enter at high tides,

were a number of elegant tree-ferns from eight to fifteen

feet high. These are generally considered to be mountain

plants, and rarely to occur on the equator at an elevation

of less than one or two thousand feet. In Borneo, in the

Aru Islands, and on the banks of the Amazon, I have

observed them at the level of the sea, and think it probable

that the altitude supposed to be requisite for them

may have been deduced from facts observed in countries

where the plains and lowlands are largely cultivated, and

most of the indigenous vegetation destroyed. Such is the

case in most parts of Java, India, Jamaica, and Brazil,

where the vegetation of the tropics has been most fully

explored.

Coming out to sea we turned northwards, and in about

two hours’ sail reached a few huts, called Langundi, where

some Galela men had established themselves as collectors

of gum-dammar, with which they made torches for the

supply of the Ternate market. About a hundred yards

back rises a rather steep hill, and a short walk having

shown me that there was a tolerable path up it, I determined

to stay here for a few days. Opposite us, and all

along this coast of Batchian, stretches a row of fine islands

completely uninhabited. Whenever I asked the reason why

no one goes to live in them, the answer always was, “ For

fear of the Magindano pirates.” Every year these scourges

of the Archipelago wander in one direction or another,

making their rendezvous on some uninhabited island, and

carrying devastation to all the small settlements around ,

robbing, destroying, killing, or taking captive all they mee

with. Their long well-manned praus escape from the

pursuit of any sailing vessel by pulling away right in the

wind’s eye, and the warning smoke of a steamer generally

enables them to hide in some shallow bay, or narrow river,

or forest-covered inlet, till the danger is passed. The only

effectual way to put a stop bo their depredations would be

to attack them in their strongholds and villages, and

compel them to give up piracy, and submit to strict

surveillance, Sir James Brooke did. this with the pirates

of the north-west coast of Borneo, and deserves the thanks

of the whole population of the Archipelago for having rid

them of half their enemies.