covered with stout paper inside and out, are strong, light,

and secure the insect-pins remarkably well. The leaflets

of the sago folded and tied side by side on the smaller

midribs form the “ atap ” or thatch in universal use, while

the product of the trunk is the staple food of some

hundred thousands of men.

When sago is to be made, a full-grown tree is selected

just before it is going to flower. It is cut down close to

the ground, the leaves and leaf-stalks cleared away, and a

broad strip of the bark taken off the upper side of the

trunk. This exposes the pithy matter, which is of a rusty

colour near the bottom of the tree, but higher up pure

white, about as hard as a dry apple, but with woody fibres

running through it about a quarter of an inch apart. This

pith is cut or broken down into a coarse powder by means

of a tool constructed for the purpose—a club of hard and

heavy wood, having a piece of sharp quartz rock firmly

imbedded into its blunt end, and projecting about half an

Y.'l.

SAGO CLUB.

inch. By successive blows of this, narrow strips of the

pith are cut away, and fall down into the cylinder formed

by the bark. Proceeding steadily on, the whole trunk is

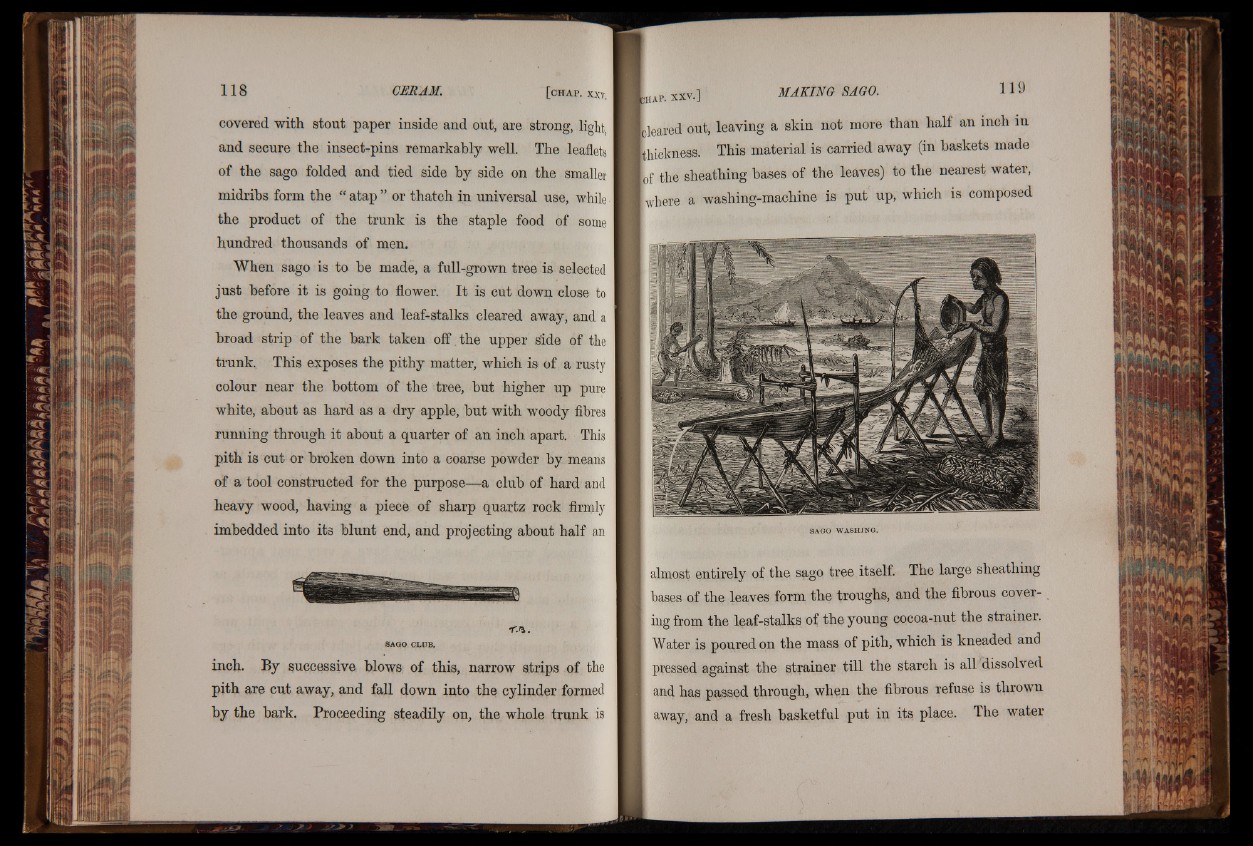

bleared out, leaving a skin not more than half an inch in

[hickness. This material is carried away (in baskets made

[of the sheathing bases of the leaves) to the nearest water,

[where a washing-machine is put up, which is composed

SAGO WASHING.

almost entirely of the sago tree itself. The large sheathing

bases of the leaves form the troughs, and the fibrous covering

from the leaf-stalks of the young cocoa-nut the strainer.

Water is poured on the mass ot pith, which is kneaded and

pressed against the strainer till the starch is all dissolved

and has passed through, when the fibrous refuse is thrown

away, and a fresh basketful put in its place. The water