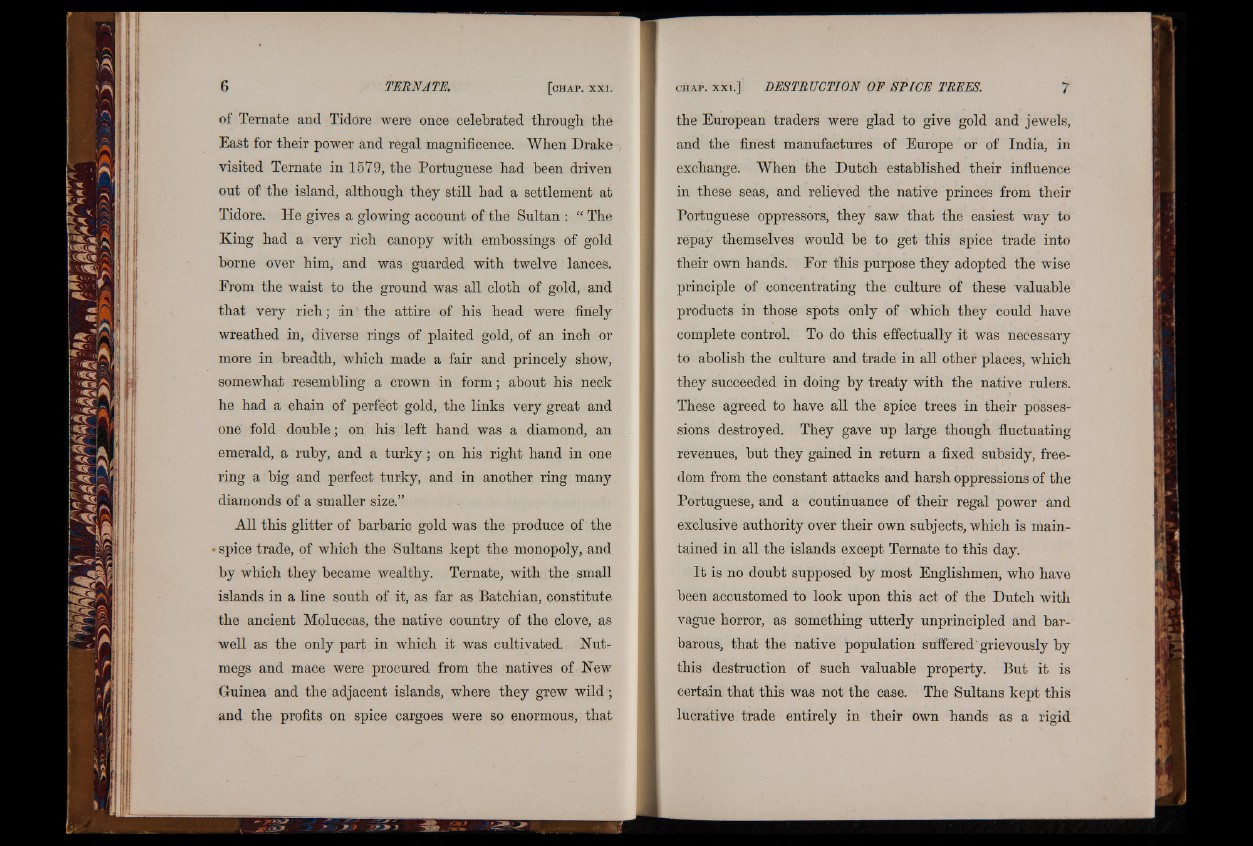

of Ternate and Tidore were once celebrated through the

East for their power and regal magnificence. When Drake

visited Ternate in 1579, the Portuguese had been driven

out of the island, although they still had a settlement at

Tidore. He gives a glowing account of the Sultan : “ The

King had a very rich canopy with embossings of gold

borne over him, and was guarded with twelve lances.

From the waist to the ground was all cloth of gold, arid

that very rich; ;in' the attire of his head were finely

wreathed in, diverse rings of plaited gold, of an inch or

more in breadth, which made a fair and princely show,

somewhat resembling a crown in form; about his neck

he had a chain of perfect gold, the links very great and

one fold double.; on his left hand was a diamond, an

emerald, a ruby, and a tu rk y ; on his right hand in one

ring a big and perfect turky, and in another ring many

diamonds of a smaller size.”

All this glitter of barbaric gold was the produce of the

spice trade, of which the Sultans kept the monopoly, and

by which they became wealthy. Ternate, with the small

islands in a line south of it, as far as Batchian, constitute

the ancient Moluccas, the native country of the clove, as

well as the only part in which it was cultivated. Nutmegs

and mace were procured from the natives of New

Guinea and the adjacent islands, where they grew wild;

and the profits on spice cargoes were so enormous, that

the European traders were glad to give gold and jewels,

and the finest manufactures of Europe or of India, in

exchange. When the Dutch established their influence

in these seas, and relieved the native princes from their

Portuguese oppressors, they saw that the easiest way to

repay themselves would be to get this spice trade into

their own hands. For this purpose they adopted the wise

principle of concentrating the culture of these valuable

products in those spots only of which they could have

complete control. To do this effectually it was necessary

to abolish the culture and trade in all other places, which

they succeeded in doing by treaty with the native rulers.

These agreed to have all the spice trees in their possessions

destroyed. They gave up large though fluctuating

revenues, but they gained in return a fixed subsidy, freedom

from the constant attacks and harsh oppressions of the

Portuguese, and a continuance of their regal power and

exclusive authority over their own subjects, which is maintained

in all the islands except Ternate to this day.

It is no doubt supposed by most Englishmen, who have

been accustomed to look upon this act of the Dutch with

vague horror, as something utterly unprincipled and barbarous,

that the native population suffered grievously by

this destruction of such valuable property. But it is

certain that this was not the case. The Sultans kept this

lucrative trade entirely in their owTn hands as a rigid