ments of a monastery, with the addition of implements, of

husbandry, the establishment being partly supported by the

manual labour of the monks ; but in general the magnitudes

of these buildings are greater than is necessary for their

inmates, and their number is disproportionate to the extent oi

the country. In addition to the labour of the priests, contributions

are obtained from Europe, and the rest of the funds is

supplied by the peasantry, who willingly give more than a fair

proportion of what they possess. p

Belonging to the convents are terraces, with patches oi

tobacco, hemp, corn, vines, and olives, usually under the protection

of the country people. In general, the Maronites are

poor; but as frugality prevails almost universally, no individual

is destitute of the necessaries of life ; and, at the same time,

no one is unreasonably desirous of more than he has. The

Maronite districts form two small and almost independent

republics; each being under an Emir belonging to one of the

principal families of the adjoining territory, over which, as a

body, the Maronites exercise considerable influence.

The country of the Druses lies southward of that of the

Maronites, and it contains several mountain districts, such as

El Shouf, El Tefahk, El Shomar, and 13 others,1 forming

as many cantons, each under an emir of ancient family, who

usually'occupies a large serai, and is comparatively wealthy.

Throughout this tract a kind of republican independence is

maintained under the Sheikh Beshir, a hereditary chieftain,

who resides at Shouf. But, by way of control, a Muhammedan,

now the Emir Beshir, is appointed by the Porte, whose

system of government consists in maintaining a sort of balance

between the Christians, to whom he is supposed secretly to

belong, and the Druses. His authority extends from Belad

Akkar to the district of Akka, but his revenue, including the

miri collected for himself, does not exceed £10,000, whilst

the Sheikh Beshir, with his feudal state and retinue, who

1 The others are El Djessain, the Kesriian, El Mdttin, El Soleima, El

Gharb, El Fokany, El Tahtany, El Djord, El Shelihar, El Menaszef, El

Aaarkoub, and El Kharroub.—Burckhardt’s Travels in Syria, pp.204, 205.

Would possess the real power in the case of a struggle, has

about £50,000 sterling.1

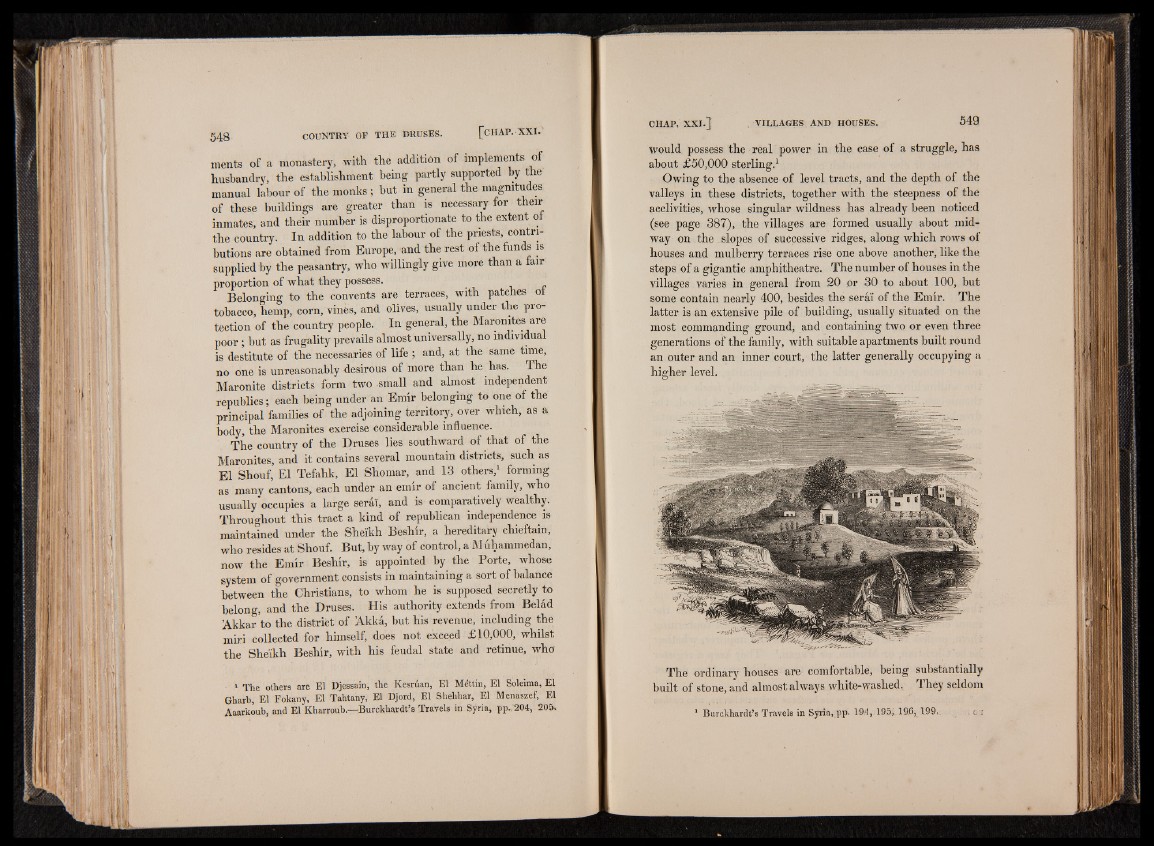

Owing to the absence of level tracts, and the depth of the

valleys in these districts, together with the steepness of the

acclivities, whose singular wildness has already been noticed

(see page 387), the villages are formed usually about midway

on the ^slopes of successive ridges, along which rows of

houses and mulberry terraces rise one above another, like the

steps of a gigantic amphitheatre. The number of houses in the

villages varies in general from 20 or 30 to about 100, but

some contain nearly 400, besides the serai of the Emir. The

latter is an extensive pile of building, usually situated on the

most commanding ground, and containing two or even three

generations of the family, with suitable apartments built round

an outer and an inner court, the latter generally occupying a

higher level.

The ordinary houses are comfortable, being substantially

built of stone, and almost always white-washed. They seldom