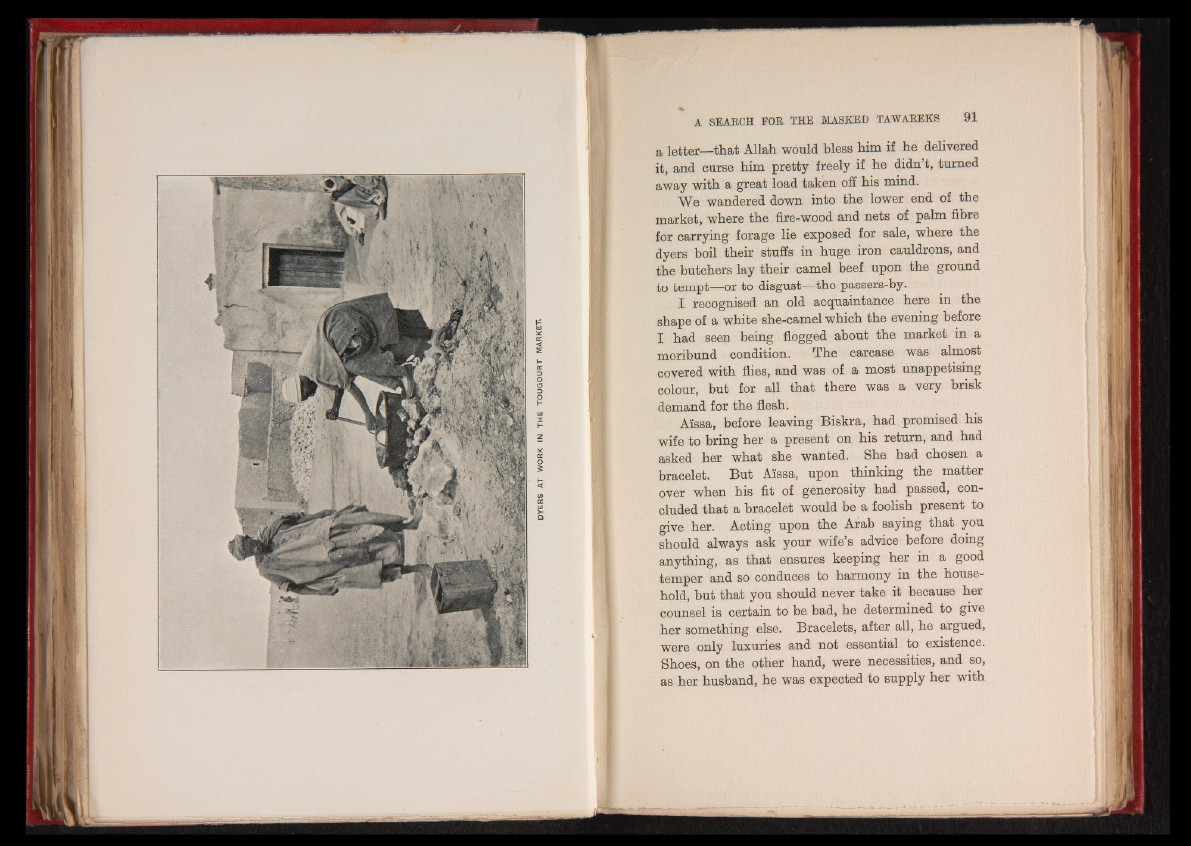

DYERS AT WORK IN THE TOUGOURT MARKET

a letter—that Allah would bless him if he delivered

it, and curse him pretty freely if he didn’t, turned

away with a great load taken off his mind.

We wandered down into the lower end of the

market, where the fire-wood and nets of palm fibre

for carrying forage lie exposed for sale, where the

dyers boil their stuffs in huge iron cauldrons, and

the butchers lay their camel beef upon the ground

to tempt—or to disgust—the passers-by.

I recognised an old acquaintance here in the

shape of a white she-camel which the evening before

I had seen being flogged about the market in a

moribund condition. The carcase was almost

covered with flies, and was of a most unappetising

colour, but for all that there was a very brisk

demand for the flesh.

Aissa, before leaving Biskra, had promised his

wife to bring her a present on his return, and had

asked her what she wanted. She had chosen a

bracelet. But Aissa, upon thinking the matter

over when his fit of generosity had passed, concluded

that a bracelet would be a foolish present to

give her. Acting upon the Arab saying that you

should always ask your wife’s advice before doing

anything,, as that ensures keeping her in a good

temper and so conduces to harmony in the household,

but that you should never take it because her

counsel is certain to be bad, he determined to give

her something else. Bracelets, after all, he argued,

were only luxuries and not essential to existence.

Shoes, on the other hand, were necessities, and so,

as her husband, he was expected to supply her with