were gone. He kept, in spite of his obvious efforts

to repress them, breaking into little nervous sniggers.

He looked as shamefaced and confused as an ordinary

Englishman would if he were compelled to appear

in public in the airy costume of his morning bath.

That ‘ brigand of the Sahara,’ great strapping fellow

as he was, positively blushed a deep, ruddy brown,

at the indignity which he was made to undergo in

exposing his face to a stranger. He hung his head

and turned his face aside in a torment of outraged

modesty and bashfulness which, though extremely

ludicrous, was almost pitiful to see.

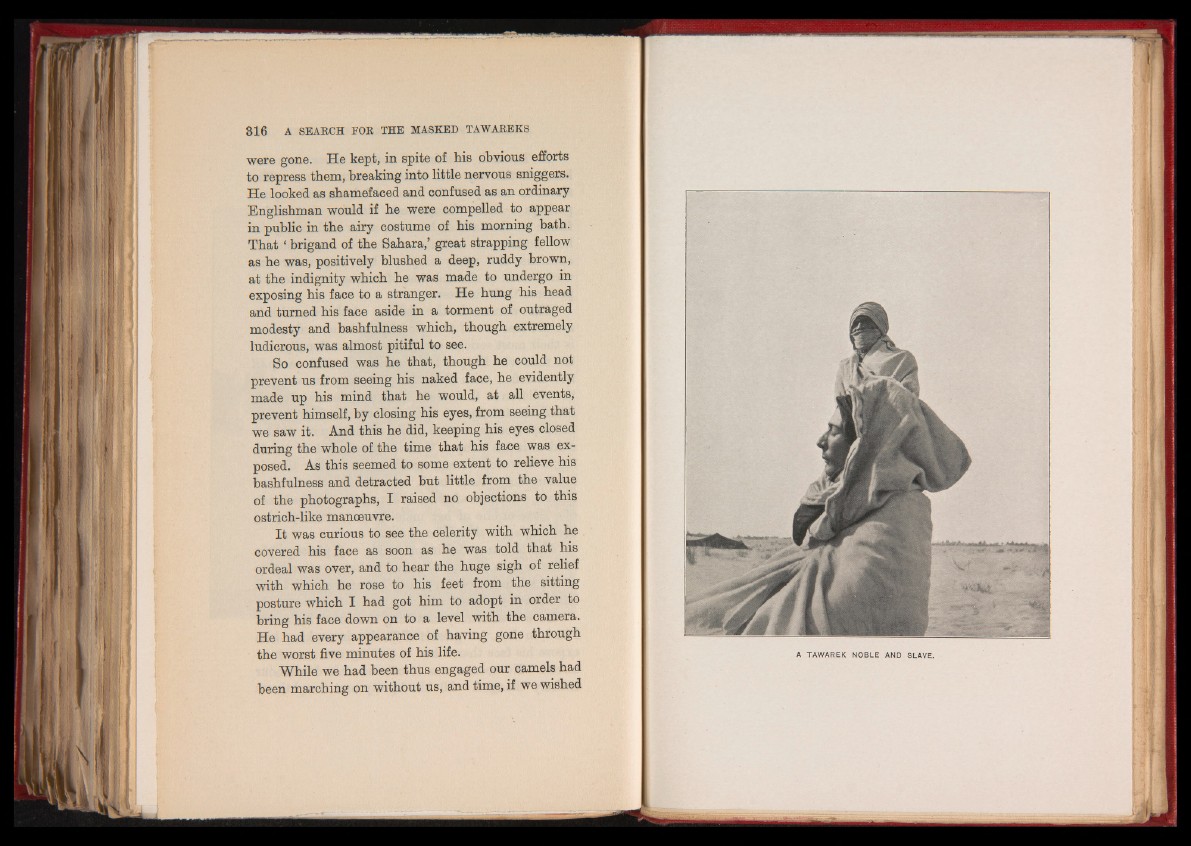

So confused was he that, though he could not

prevent us from seeing his naked face, he evidently

made up his mind that he would, at all events,

prevent himself, by closing his eyes, from seeing that

we saw it. And this he did, keeping his eyes closed

during the whole of the time that his face was exposed.

As this seemed to some extent to relieve his

bashfulness and detracted but little from the value

of the photographs, I raised no objections to this

ostrich-like manoeuvre.

It was curious to see the celerity with which he

covered his face as soon as he was told that his

ordeal was over, and to hear the huge sigh of relief

with which he rose to his feet from the sitting

posture which I had got him to adopt in order to

bring his face down on to a level with the camera.

He had every appearance of having gone through

the worst five minutes of his life.

While we had been thus engaged our camels had

been marching on without us, and time, if we wished