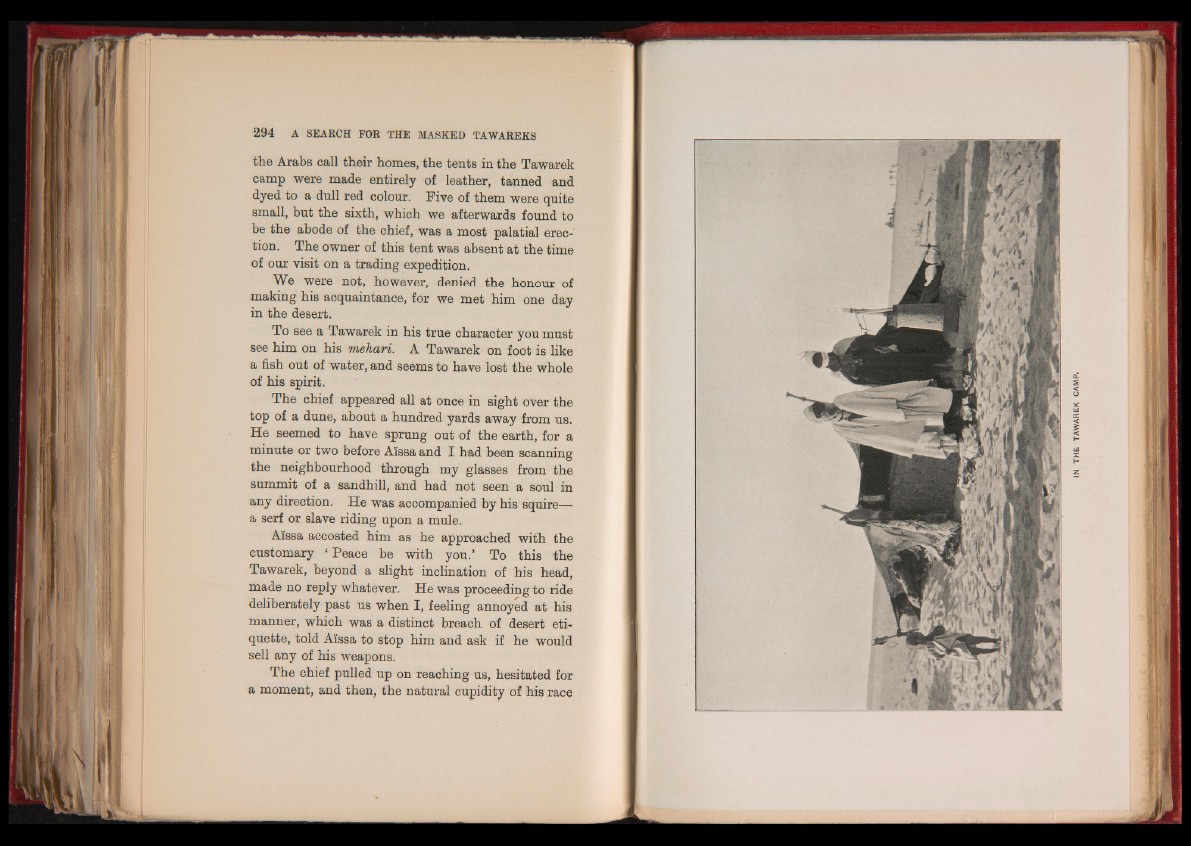

the Arabs call their homes, the tents in the Tawarek

camp were made entirely of leather, tanned and

dyed to a dull red colour. Five of them were quite

small, but the sixth, which we afterwards found to

be the abode of the chief, was a most palatial erection.

The owner of this tent was absent at the time

of our visit on a trading expedition.

We were not, however, denied the honour of

making his acquaintance, for we met him one day

in the desert.

To see a Tawarek in his true character you must

see him on his méhari. A Tawarek on foot is like

a fish out of water, and seems to have lost the whole

of his spirit.

The chief appeared all at once in sight over the

top of a dime, about a hundred yards away from us.

He seemed to have sprung out of the earth, for a

minute or two before Aïssa and I had been scanning

the neighbourhood through my glasses from the

summit of a sandhill, and had not seen a soul in

any direction. He was accompanied by his squire—

a serf or slave riding upon a mule.

Aïssa accosted him as he approached with the

customary ‘Peace be with you.’ To this the

Tawarek, beyond a slight inclination of his head,

made no reply whatever. He was proceeding to ride

deliberately past us when I, feeling annoyed at his

manner, which was a distinct breach of desert etiquette,

told Aïssa to stop him and ask if he would

sell any of his weapons.

The chief pulled up on reaching us, hesitated for

a moment, and then, the natural cupidity of his race