tails about continuously and tripping daintily from

one bush to another as they feed.

When the hunter has got to within some hundred

and fifty yards of the herd, he turns off to one side

and, keeping himself all the time well concealed

behind the camel, commences to approach in a sort

of spiral, circling round and round his game, edging

towards them when they are not looking and turning

away again when they raise their heads and glance

in his direction.

In this manner he has little difficulty in approaching

to within fifty yards or so of the herd, and at

this range an Arab gun—if it goes off—is fairly

accurate.

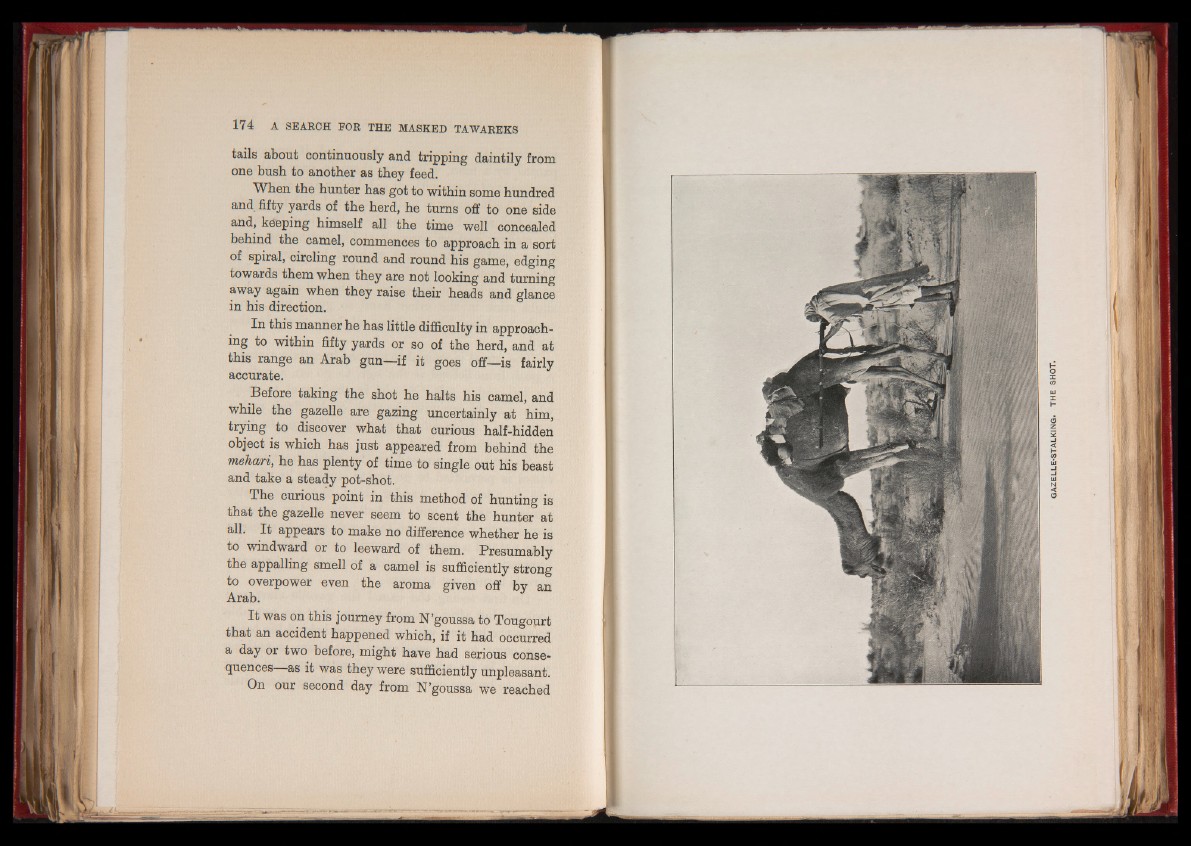

Before taking the shot he halts his camel, and

while the gazelle are gazing uncertainly at him,

trying to discover what that curious half-hidden

object is which has just appeared from behind the

mehari, he has plenty of time to single out his beast

and take a steady pot-shot.

The curious point in this method of hunting is

that the gazelle never seem to scent the hunter at

all. It appears to make no difference whether he is

to windward or to leeward of them. Presumably

the appalling smell of a camel is sufficiently strong

to overpower even the aroma given off by an

Arab.

It was on this journey from N’goussa to Tougourt

that an accident happened which, if it had occurred

a day or two before, might have had serious consequences

as it was they were sufficiently unpleasant.

On our second day from N’goussa we reached