sultans of Wargla and Tougourt, and even Roman

coins are found among them. The majority of the

pieces are so battered and worn as to be quite defaced,

but now and then a good specimen can be

found, and as seven of them of whatever description

go to a single French sou, anyone interested in

numismatics would be able to make a collection of

them at a very slight cost.

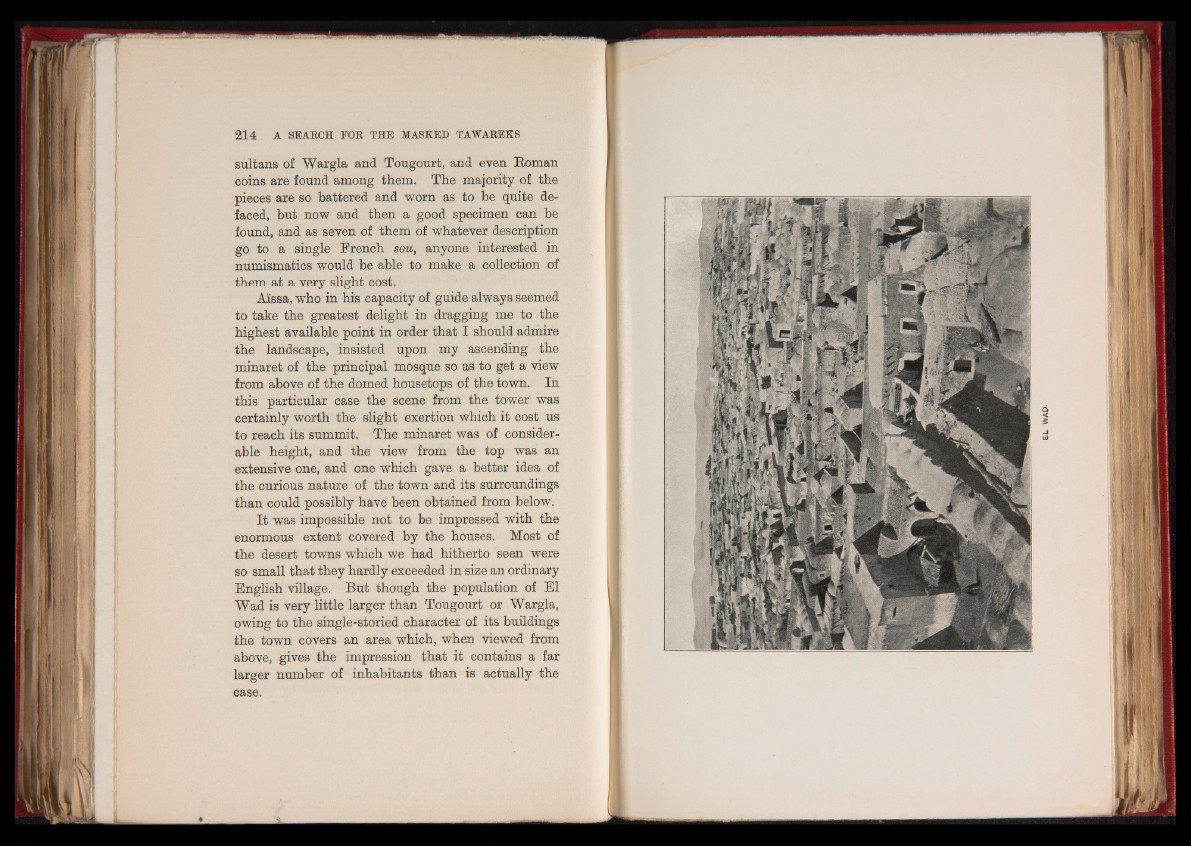

Alssa, who in his capacity of guide always seemed

to take the greatest delight in dragging me to the

highest available point in order that I should admire

the landscape, insisted upon my ascending the

minaret of the principal mosque so as to get a view

from above of the domed housetops of the town. In

this particular case the scene from the tower was

certainly worth the slight exertion which it cost us

to reach its summit. The minaret was of considerable

height, and the view from the top was an

extensive one, and one which gave a better idea of

the curious nature of the town and its surroundings

than could possibly have been obtained from below.

It was impossible not to be impressed with the

enormous extent covered by the houses. Most of

the desert towns which we had hitherto seen were

so small that they hardly exceeded in size an ordinary

English village. But though the population of El

Wad is very little larger than Tougourt or Wargla,

owing to the single-storied character of its buildings

the town covers an area which, when viewed from

above, gives the impression that it contains a far

larger number of inhabitants than is actually the

case.