position of having either to back him up in some

thundering lie, or to get out of the difficulty as best

I might.

In this case, however, he had done me a service,

for as soon as I had had time to recover from the

first shock of the staggering request which had been

made to me, it struck me that I might make use of

the thirst for knowledge of those Tawareks to obtain

before their faces those very photos which I had surreptitiously

been trying to take behind their backs.

I told them that I could not show them the

interior of the box, as that would necessitate taking

it to pieces, and, as it was a delicate machine, would

probably spoil it, but that if they would stand in

front of it they would be able to see how one part of

it worked, and I told them to look at the shutter.

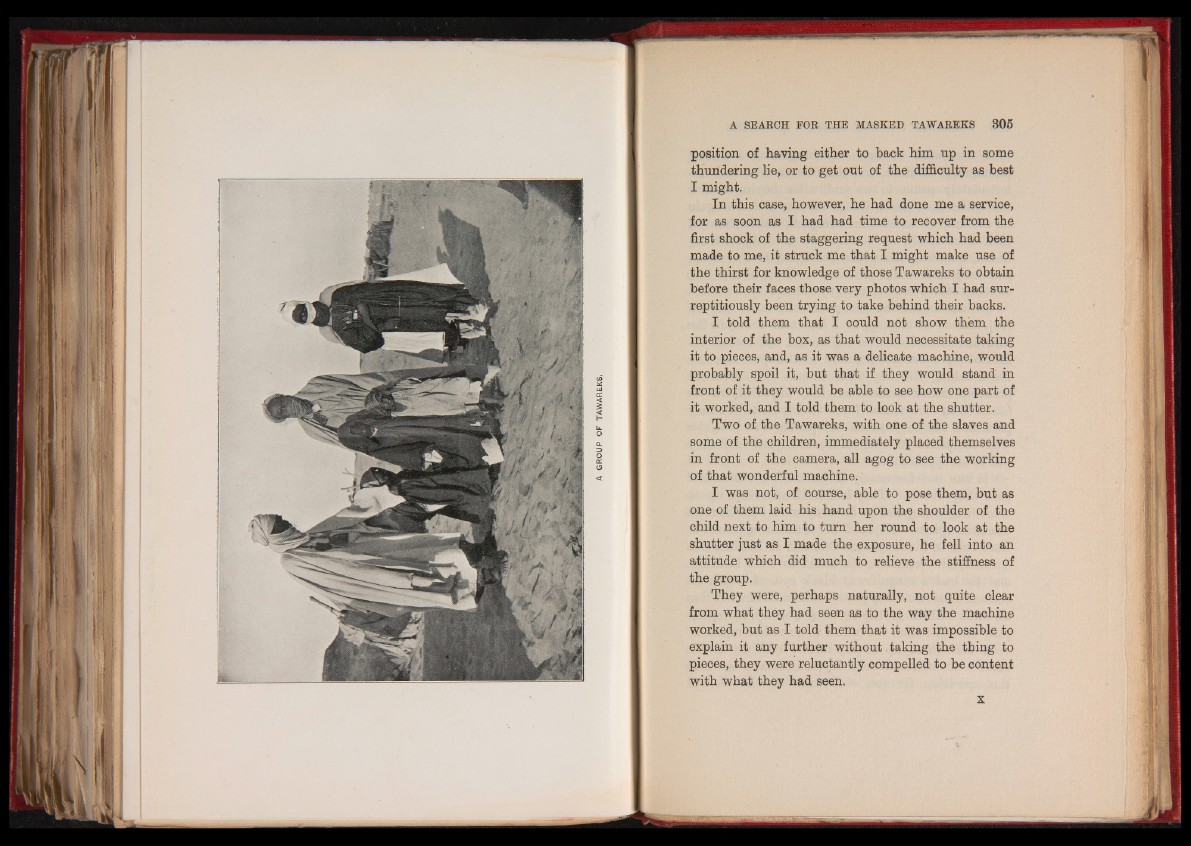

Two of the Tawareks, with one of the slaves and

some of the children, immediately placed themselves

in front of the camera, all agog to see the working

of that wonderful machine.

I was not, of course, able to pose them, but as

one of them laid his hand upon the shoulder of the

child next to him to turn her round to look at the

shutter just as I made the exposure, he fell into an

attitude which did much to relieve the stiffness of

the group.

They were, perhaps naturally, not quite clear

from what they had seen as to the way the machine

worked, but as I told them that it was impossible to

explain it any further without taking the thing to

pieces, they were reluctantly compelled to be content

with what they had seen.