weeks before and obtained a certain amount of

relief from doing so.

The desert, which on our southward march had

seemed to me so pretty, now possessed no beauty

whatever in my eyes. It appeared to be the most

arid and horrid waste in existence. I began to hate

the very sight of it.

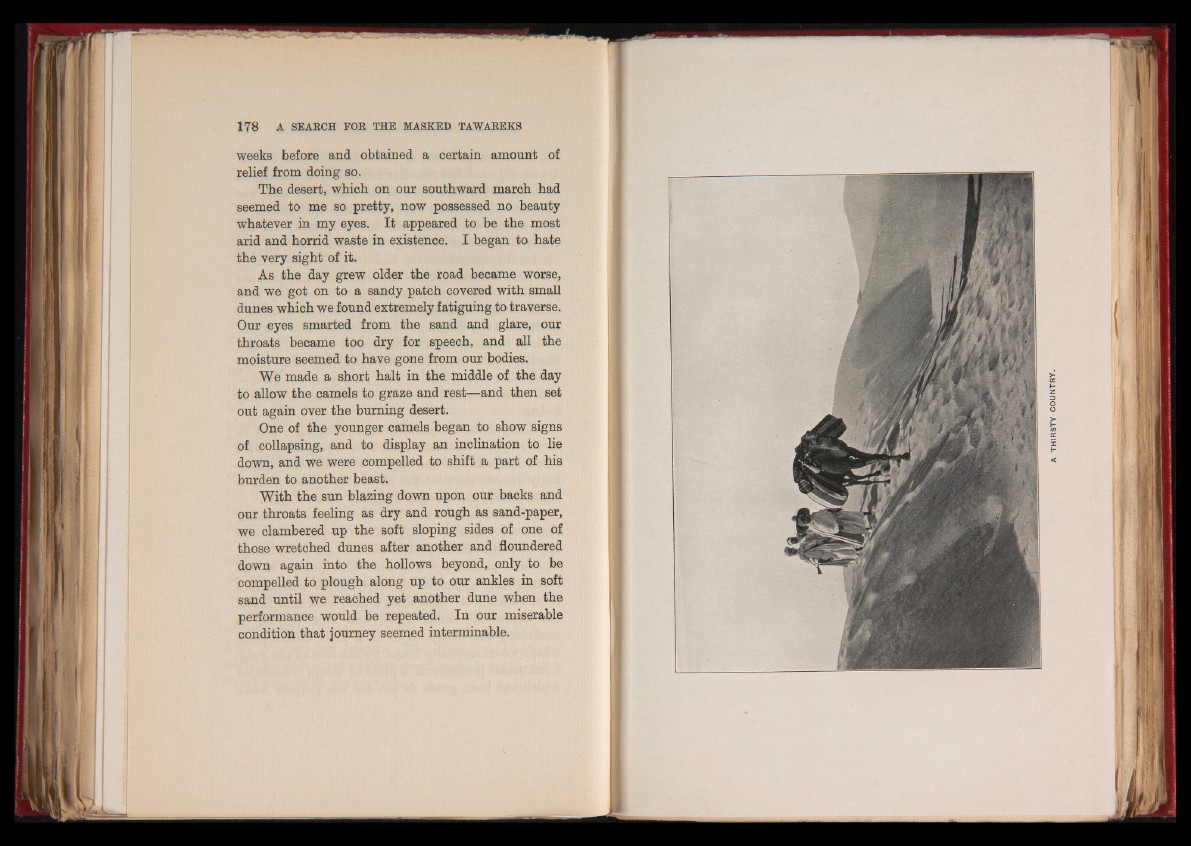

As the day grew older the road became worse,

and we got on to a sandy patch covered with small

dunes which we found extremely fatiguing to traverse.

Our eyes smarted from the sand and glare, our

throats became too dry for speech, and all the

moisture seemed to have gone from our bodies.

We made a short halt in the middle of the day

to allow the camels to graze and rest—and then set

out again over the burning desert.

One of the younger camels began to show signs

of collapsing, and to display an inclination to lie

down, and we were compelled to shift a part of his

burden to another beast.

With the sun blazing down upon our backs and

our throats feeling as dry and rough as sand-paper,

we clambered up the soft sloping sides of one of

those wretched dunes after another and floundered

down again into the hollows beyond, only to be

compelled to plough along up to our ankles in soft

sand until we reached yet another dune when the

performance would be repeated. In our miserable

condition that journey seemed interminable.