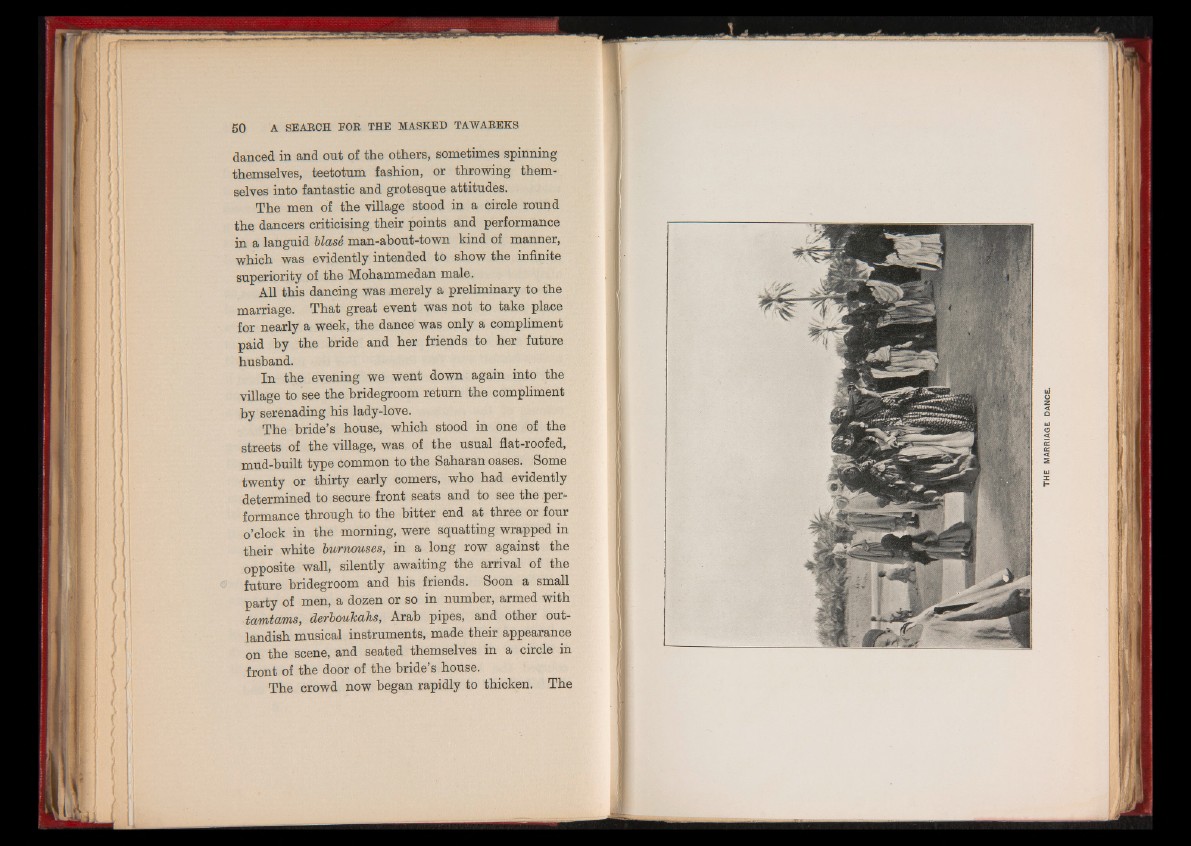

danced in and out of the others, sometimes spinning

themselves, teetotum fashion, or throwing themselves

into fantastic and grotesque attitudes.

The men of the village stood in a circle round

the dancers criticising their points and performance

in a languid blasS man-about-town kind of manner,

which was evidently intended to show the infinite

superiority of the Mohammedan male.

All this dancing was merely a preliminary to the

marriage. That great event was not to take place

for nearly a week, the dance was only a compliment

paid by the bride and her friends to her future

husband.

In the evening we went down again into the

village to see the bridegroom return the compliment

by serenading his lady-love.

The bride’s house, which stood in one of the

streets of the village, was of the usual flat-roofed,

mud-built type common to the Saharan oases. Some

twenty or thirty early comers, who had evidently

determined to secure front seats and to see the performance

through to the bitter end at three or four

o’clock in the morning, were squatting wrapped in

their white burnouses, in a long row against the

opposite wall, silently awaiting the arrival of the

future bridegroom and his friends. Soon a small

party of men, a dozen or so in number, armed with

tamtams, derboukahs, Arab pipes, and other outlandish

musical instruments, made their appearance

on the scene, and seated themselves in a circle in

front of the door of the bride’s house.

The crowd now began rapidly to thicken. The