The zyg om a tic diameter is the distance, in a right line, between the most

prominent points of the zygomae.

The fa c ia l angle* is ascertained by an instrument of ingenious construction

* The facial angle, which was first proposed by the learned Professor Camper, is measured in'the

following manner: a line called the facial line, is drawn from the anterior edge of the upper jaw, (or,

if the tooth projects beyond the jaw, from the tooth itself,) to the most prominent part o f the forehead,

which is usually the space between the superciliary ridges. A second or horizontal line, is drawn

through the external opening of the ear (meatus auditorius) till it touches the base of the nostrils,

between the terminal roots of the front incisor teeth, and from this point it is still prolonged until it

meets with the facial line already described: hence the two lines may meet at, or very near, the nasal

spine, or base of the nose; but in other instances the decussation of the lines occurs at a point

considerably anterior to the bone. It is obvious that an angle will be formed where these lines thus

intersect each other, and this is the facial angle. For example, notice the annexed wood cut, (No. 1,)

which represents the skull of the Cowalitsk already

figured in this work, (see Plate 50.) The line A, B,

is the facial line, extending, as just observed, from the

anterior margin of the upper jaw to the most prominent

part of the os frontis; the second or horizontal

line, is represented between the points C and D, and

for the purpose of having a fixed point for its anterior

termination, I have uniformly carried it to the nasal

spine, above and between the roots of the two front incisor teeth. The point E , where these lines

decussate each other, is the facial angle, which in the present instance will be found to measure about

sixty-six degrees.—The second wood cut (No. 2 ) represents the lines

as drawn on a much better formed head, that of a Peruvian Indian,

in which the angle at E measures seventy-six degrees.

The most casual inspection of these diagrams will satisfy any

one that the facial angle is no criterion of mental intelligence; and in

justice to Camper we must add that he does not assert it to be so.

In fact it chiefly gives the projection of the face in relation to the

head, without conveying the least idea of the capacity of the cranium,

whichis often the same.in heads whose diameters are altogether different. The mere obliquity of

the teeth contracts the'angle; and what is yet more important, the space bettyeen the eyes from

whence the facial line is drawn, may be very prominent, so as to give an anglb of eighty degrees,

while the forehead itself retreats so rapidly, that if the fecial line were made to touch it, the resulting

angle would not perhaps exceed sixty-five degrees.

.«Th e maximum angle that can be embraced by the facial lines,” says Camper, “ is lp.0S: if we

advance these lines stiU further, the head becomes pretematurally large, as in hydrocephalus. But it

is surprising to observe that the most ancient Greek artists'have chosen the very maximum of the

facial angle, while the best Roman graveurs were.satisfiedwith the angle of 95°:

“ I have thus established the two extremes of obliquity in the facial line, viz: from 70° to 100°..

and ready application, which has received so many additions from the suggestions

of different individuals, that its invention cannot be ascribed to any one person.

The original idea, however, originated with my friend Dr. Turnpennypjand I

have much pleasure in explaining it, inasmuch as it appears to me to supersede

tïjlhcse embrace all the gradations, from the head of the Negro to the sublime beauty of the ancient

Greek models.. If-we descend below 70° we have an orang ta a n g j.< |! | monkey | j f we descend still

lower we have a dog or a bird—a shjpe,for example, qf: which the facial line is almost parallel with

a horizontal plane.”—(Dissertation sur lés üffêrence réelles, Src., p. 42, t a | j g

Professor Blumenbach has d e n p th a t the genuine antique heads present an aiïgp of 95» or 100°,

and supposes that s i i* measurements could only be derived from incorrect copiés ( Di Wiseman,

thewfher hand, remarks, whoever will examine the heads » J u p ite r in the Vatican Museum,

p a r tic p la r l^ e bpst in the/ Jargeicii^lar Trail, or the more defaced heads of the Elgin marbles, will be

Satisfied that Camper is accurate in this respect.S=-( Twelve factures, fyc., p. 105.J

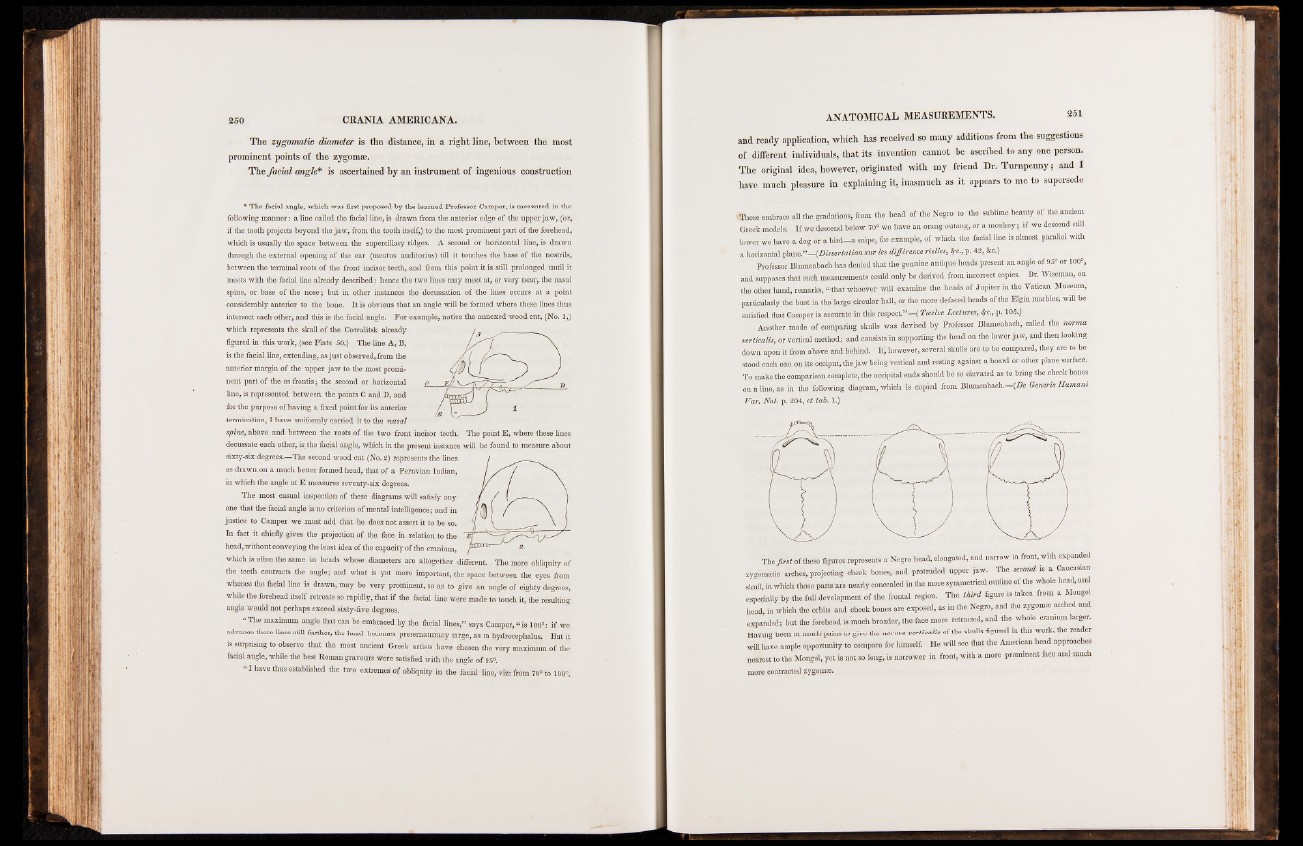

Another mode of comparing Skulls, was devised by Professor Blumenbach; called the norma

verticdUs, or Verticàl method; and consists in supporting the head on the lower jaw, and 'h e u ^ k in g

down upon it from above and behind. If, hdwever,. several skulls are to Be compared, they are to be

stood each .one on its occiput, the jaw being vertical and resting against a board or other plane surface.

To make the comparison complete, the occipital ends should be so elevated as to bring-the cheek bones

I n a linelas in the following diagram, w hich is! copied from Blumenbach.—(He Generis Humane

Var. Nat. p. 204, et tab. 1.)

TheySret of these figures represents a Negro head, elongated, add narrow-in ftont, with expanded

zygomatic arches, projecting cheek bories, and protruded upper jaw. The second is a Caucasian

bkull in which those parts are nearly concealed in the more symmetrical outline of the whole head, and

especially by the full development of the frontal region. The third figureds.taken from a Mongol

head, in which the orbits and cheek bones are exposed,, as in the Negro, and the zygomas arched and

expanded; but the forehead is much broader, the face more retracted,-and the whole cranium larger.

Having been at much pains to give m norma vertiealis of M skulls figured in this work, the reader

will have ample opportunity to compare for himself. He will see that the American head approaches

nearest to the Mongol, yet is not so long, is narrower in front, with a more prominent face and much

more contracted zygomas.