infant is thus suffered to remain from four to eight months, or until the sutures of

the skull have in some measure united, and the bone become solid and firm. It

is seldom or never taken from the cradle, except in case of severe illness, until the

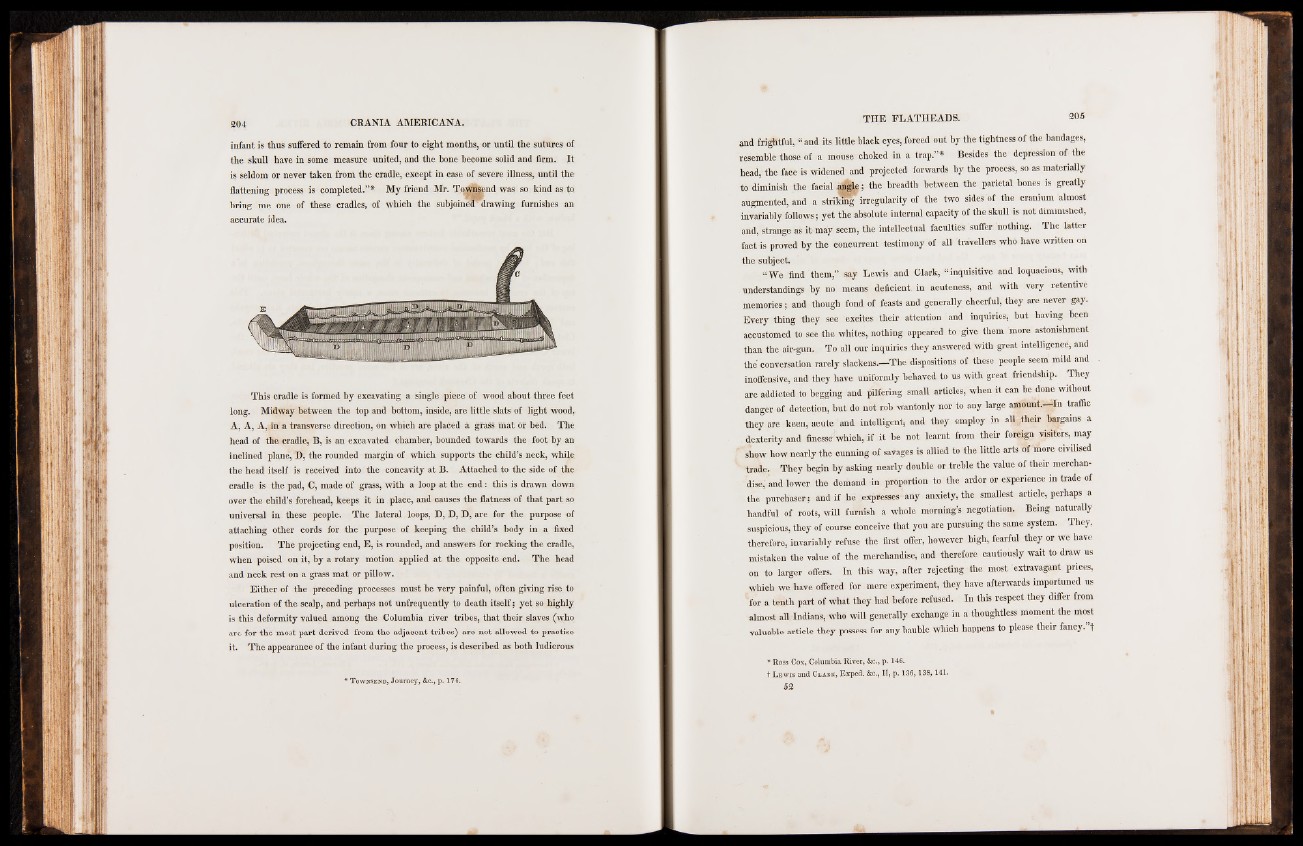

flattening process is completed.”* My friend Mr. Toyrasend was so kind as to.

bring me one of these cradles, of which the subjoined drawing furnishes an

accurate idea.

This cradle is formed by excavating a single piece of wood about three feet

long. Midway between the top and bottom, inside, are little slats of light wood,

A, A, A, in a transverse direction, on which are placed a grass mat or bed. The

head of the cradle, B, is an excavated chamber, bounded towards the foot by an

inclined plane, D, the rounded margin of which supports the child’s neck, while

the head itself is received into the concavity at B. Attached to the side of the

cradle is the pad, C, made of grass, with a loop at the end: this is drawn down

over the child’s forehead, keeps it in place, and causes the flatness of that part so

universal in these people. The lateral loops, D, D, D, are for the purpose of

attaching other cords for the purpose of keeping the child’s body in a fixed

position. The projecting end, E, is rounded, and answers for rocking the cradle,

when poised on it, by a rotary motion applied at the opposite end. The head

and neck rest on a grass mat or pillow.

Either of the preceding processes must be very painful, often giving rise to

ulceration of the scalp, and perhaps not unfrequently to death itself; yet so highly

is this deformity valued among the Columbia river tribes, that their slaves (who

are for the most part derived from the adjacent tribes) are not allowed to practise

it. The appearance of the infant during the process, is described as both ludicrous

T ownsend, Journey, &c., p. 176.

and frightful, “ and its little black eyes, forced out by the tightness of the bandages,

resemble those of a mouse choked in a trap.”* Besides the depression of. the

head, the face is widened and projected forwards by the process, so as materially

to diminish .the facial the breadth between the parietal bones is greatly

augmented, and a s tr iS g irregularity of the two sides of the cranium almost

invariably follows; yet the absolute internal capacity of the skull is not diminished,

and, strange as it may seem, the intellectual faculties, suffer nothing. The latter

fact is proved by the concurrent testimony of all travellers who have written on

the subject.

“We find them,” say Lewis and Clark, “inquisitive and loquacious, with

understandings by no means deficient, in acuteness, and with very retentive

memories ; and though fond of feasts and generally cheerful, they are never gay.

Every thing they see excites their attention and inquiries, but having been

accustomed to see the whites, nothing appeared to,'give them more astonishment

than the air-gun. To all our inquiries they answered with great intelligence, and

the conversation rarely slackens.—The dispositions of these people seem’ mild and

inoffensive, and they have uniformly behaved to us with great friendship. They

are addicted to begging and pilfering small articles, when it can be done without

danger of detection, but do not rob wantonly nor to any large amount.-Mn traffic

they are keen, acute and intelligent, and they employ in all „their %|gains a

dexterity and finessff which, if it be not learnt from their foreign visiters, may

' show how nearly the cunning of savages is allied to the little arts 'more civilised

trade. They begin by asking nearly double or treble the value of their merchandise;

and lower the demand in proportion to the ardor or experience in trade of

the purchaser ; and if he .expresses'any anxiety, the smallest article, perhaps a

handful of roots, will furnish a whole morning’s negotiation. Being naturally

suspicious, they of course conceive that you are pursuing the same system. They,

therefore, invariably refuse the first offer, however high, fearful they or we have

mistaken the value of the merchandise, and therefore cautiously wait to draw us

on to larger offers. In this way, after rejecting the most extravagant prices,

which we have offered for mere experiment, they have afterwards importuned us

‘•for a tenth part of what they had before refused. In this respect they differ from

almost all Indians, who will generally exchange in a thoughtless moment the most

valuable article they possess for any bauble which happens to please their fancy, t

* Ross Cox, Columbia ’River, &c., p. 146.

t L ew is and Clark, Exped. &c., II, p. 136, 138, 141.

52