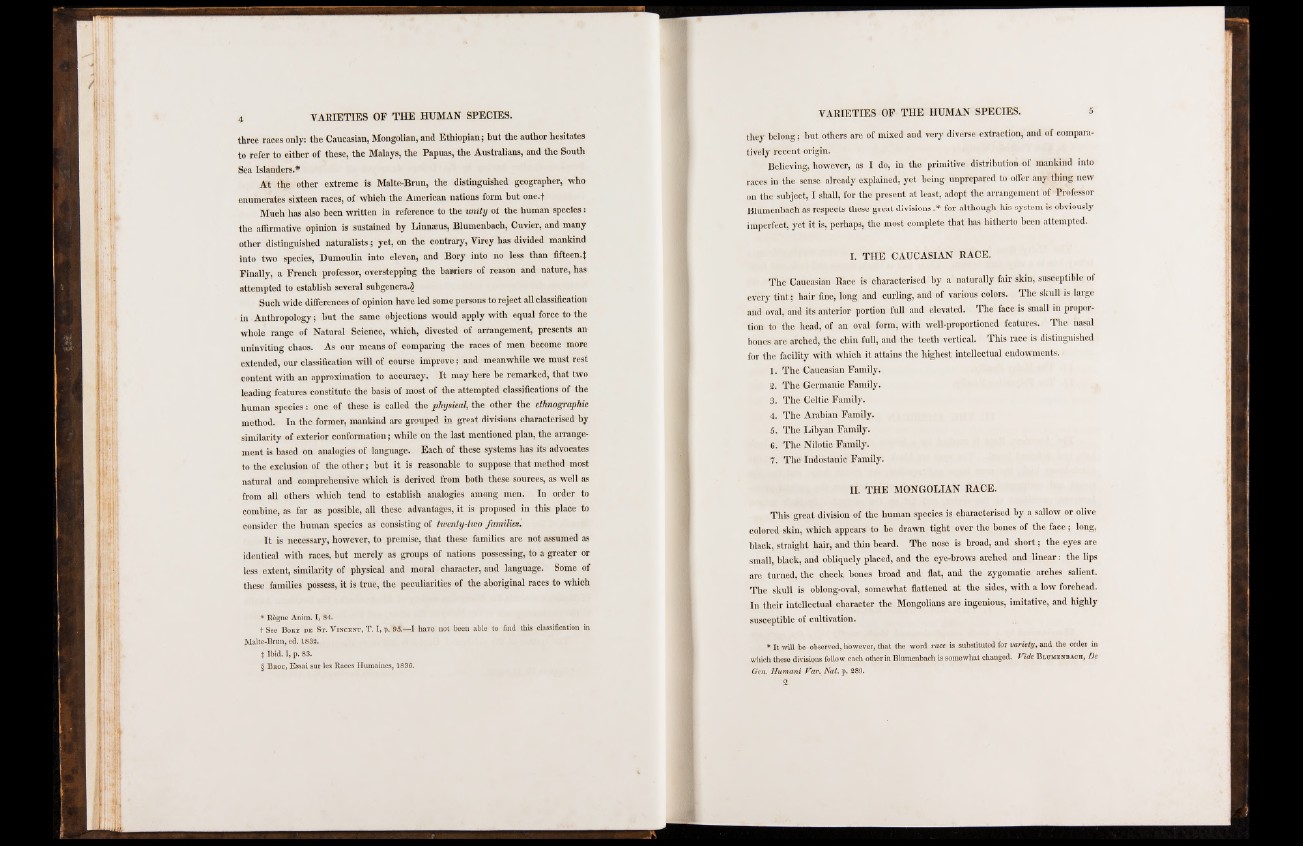

three races only: the Caucasian, Mongolian, and Ethiopian; hut the author hesitates

to refer to either of these, the Malays, the Papuas, the Australians, and the South

Sea Islanders.*

At the other extreme is Malte-Brun, the distinguished geographer, who

enumerates sixteen races, of which the American nations form hut one.!1

Much has also been written in reference to the unity of the human species:

the affirmative opinion is sustained by Linnaeus, Blumenbach, Cuvier, and many

other distinguished naturalists; yet, on the contrary, Virey has divided mankind

into two species, Dumoulin into eleven, and Bory into no less than fifteen.};

Finally, a French professor, overstepping the barriers of reason and nature, has

attempted to establish several subgenera.$

Such wide differences of opinion have led some persons to reject all classification

in Anthropology; hut the same objections would apply with equal force to the

whole range of Natural Science, which, divested of arrangement, presents an

uninviting chaos. As our means of comparing the races of men become more

extended, our classification will of course improve; and meanwhile we must rest

content with an approximation to accuracy. It may here he remarked, that two

leading features constitute the basis of most of the attempted classifications of the

human species: one of these is called the physical, the other the ethnographic

method. In the former, mankind are grouped in great divisions characterised by

similarity of exterior conformation; while on the last mentioned plan, the arrangement

is based on analogies of language. Each of these systems has its advocates

to the exclusion of the other; hut it is reasonable to suppose that method most

natural and comprehensive which is derived from both these sources, as well as

from all others which tend to establish analogies among men. In order to

combine, as far as possible, all these advantages, it is proposed in this place to

consider the human species as consisting of twenty-two families.

It is necessary, however, to premise, that these families are not assumed as

identical with races, hut merely as groups of nations possessing, to a greater or

less extent, similarity of physical and moral character, and language. Some of

these families possess, it is true, the peculiarities of the aboriginal races to which * §

* Règne Anim. T, 84.

t See Bory de St. Vincent, T. I, p. 95.—I hâve not been able to find this classification in

Malte-Brun, ed. 1832.

t Ibid. I, p. 83.

§ Broc, Essai sur les Races Humaines, 1836.

they belong; but others are of mixed and very diverse extraction, and of comparatively

recent origin.

Believing, however, as I do, in the primitive distribution of mankind into

races in the sense already explained, yet being unprepared to offer any thing new

on the subject, I shall, for the present at least, adopt the arrangement of Professor

Blumenbach as respects these great divisions :* for although his system is obviously

imperfect, yet it is, perhaps, the most complete that has hitherto been attempted.

I. THE CAUCASIAN RACE.

The Caucasian Race is characterised by a naturally fair skin, susceptible of

every tint; hair fine, long and curling, and of various colors. The skull is large

and oval, and its anterior portion full and elevated. The face is small in proportion

to the head, of an oval form, with well-proportioned features. The nasal

bones are arched, the chin full, and the teeth vertical. This race is distinguished

for the facility with which it attains the highest intellectual endowments.

1. The Caucasian Family.

2. The Germanic Family.

3. The Celtic Family.

4. The Arabian Family.

5. The Libyan Family.

6. The Nilotic Family.

7. The Indostanic Family.

II. THE MONGOLIAN RACE.

This great division of the human species is characterised by a sallow or olive

colored skin, which appears to be drawn tight over the bones of the face; long,

black, straight hair, and thin beard. The nose is broad, and short; the eyes are

small, black, and obliquely placed, and the eye-brows arched and linear: the lips

are turned, the cheek bones broad and flat, and the zygomatic arches salient.

The skull is oblong-oval, somewhat flattened at the sides, with a low forehead.

In their intellectual character the Mongolians are ingenious, imitative, and highly

susceptible of cultivation.

* It will be observed, however, that the word race is substituted for variety, and the order in

which these divisions follow each otherin Blumenbach is somewhat changed. Vide Blumenbach, De

Gen. Humani P a i\N a t. p. 289.