84

84 Fig. 85

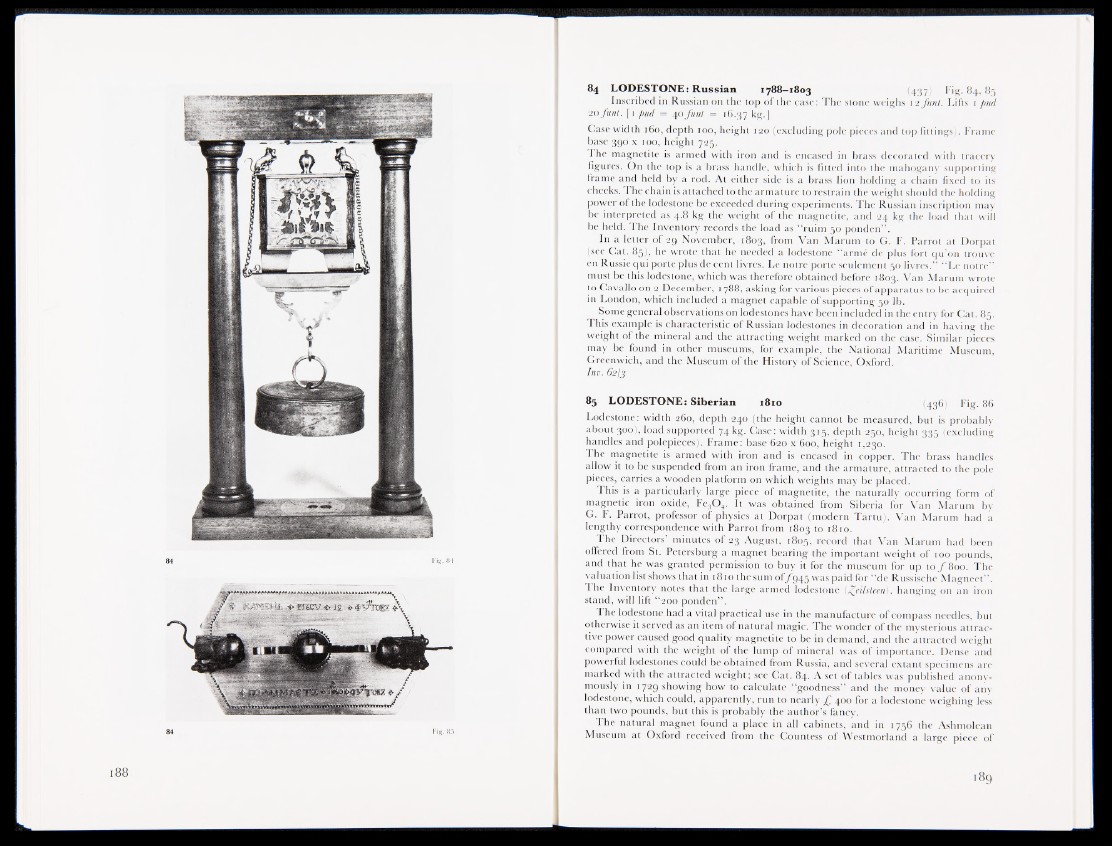

84 LODESTONE: Russian 1788—1803 (437) Fig. 84, 85

Inscribed in Russian on the top of the case: The stone weighs 12 funt. Lifts 1 pud

20 junl. fj ) pud = 40 funt - 16.37 kg-]

Case width 160, depth 100, height 120 (excluding pole pieces and top fittings). Frame

base 390 x 100, height 725.

The magnetite is armed with iron and is encased in brass decorated with tracery

figures. On the top is a brass handle, which is fitted into the mahogany supporting

frame and held by a rod. At either side is a brass lion holding a chain fixed to its

cheeks. The chain is attached to the armature to restrain the weight should the holding

power of the lodestone be exceeded during experiments. The Russian inscription may

be interpreted as 4.8 kg'the weight of the magnetite, and 24 kg the load that will

be held. The Inventory records the load as “ ruim 50 ponden” .

In a letter of 29 November, 1803, from Van Marum to G. F. Parrot at Dorpat

(see Cat. 85^ he wrote that he needed a lodestone “ armé de plus fort qu’on trouve

en Russie qui porte plus de cent livres. Le notre porte seulement 50 livres.” “ Le notre”

must be this»destone, which was therefore obtained before 1803. Van Marum wrote

to Cavallo on 2 December, 1788, asking for various pieces of apparatus to be acquired

in London, which included a magnet capable of supporting 50 lb.

Some general observations on lodestones have been included in the entry for Cat. 85.

This example is characteristic of Russian lodestones in decoration and in having the

weight of the mineral and the attracting weight marked on the case. Similar pieces

may be found in other museums, for example, the National Maritime Museum,

Greenwich, and the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford.

InVi

85 LODESTONE: Siberian 1810 (436) Fig. 86

Lodestone: width 260, depth 240 (the height cannot be measured, but is probably

about 3,00), load supported 74 kg. Case: width 315, depth 250, height 335 (excluding

handles and polepieces). Frame: base 620 x 600, height 1,230.

The magnetite is armed with iron and is encased in copper. The brass handles

allow it to be suspended from an iron frame, and the armature, attracted to the pole

pieces, carries a wooden platform on which weights may be placed.

This is a particularly large piece'0 magnetite, the naturally occurring form of

magnetic iron oxide, Fe30 4. It was obtained from Siberia for Van Marum by

G. F. Parrot, profksfor of physics at Dorpat (modern Tartu). Van Marum had a

lengthy correspondence with Parrot from 1803 to 1810.

The Directors’ minutes of 23 August, 1805:, record that Van Marum had been

offeredwjrom St. Petersburg a magnet bearing the important weight of 100 pounds,

and that he was granted permission to buy it for the museum for up to ƒ 800. The

valuation list shows that in 18 to thesum of/g.-p; was paid for “de Russische Magneet” .

The Inventory notes that the large armed lodestone ifeilsteetP,, hanging on an iron

stand, will lift “ 200 ponden” .

The lodestone had a vital practical use in the manufacture of compass needles, but

otherwise it served as an item of natural magic. The wonder of the mysterious attractive

power caused good quality magnetite to be in demand, and the attracted weight

compared with the weight of the lump of mineral, was of importance. Dense and

powerful lodestones could be obtained from Russia, and several extant specimens are

marked with the attracted weight; see Cat. 84. A set of tables was published anonymously

in 1729 showing how to calculate “goodness” and the money value of any

lodestone, which could, apparently, run to nearly f 400 for a lodestone weighing less

than two pounds, but this is probably the author’s fancy.

The natural magnet found a place in all cabinets, and in 1756 the Ashmolean

Museum at Oxford received from the Countess of Westmorland a large piece of