casing, air may be drawn in at the centre and expelled through a tube set in the

outer rim. The central, side tube can have a flexible extension tube fitted to it.

Early in the 18th century there was interest in providing fresh air in ships, hospitals,

prisons and mines, and Stephen Hales published a book called The Ventilators.

Desaguliers described his machines, “ ... calling the Wheel a centrifugal or blowing

Wheel, and the Man that turn’d it a Ventilator” (1744 p. 563), to the Royal Society

on 13 June, 1734, when he produced a model to a scale of 1:12. In a Postscript to the

second volume of A Course of Experimental Philosophy (1744) > Desaguliers tells the history

of his experiments with air-conditioning devices, which he makes out as-a hard-luck

story. He does, however, seem to have fitted a turbine blower into the House of

Commons in 1736.

Hales (1743)1 Desaguliers (4 744) 556-568, XLVI, the model is a copy of this design.

Inv. 36)2

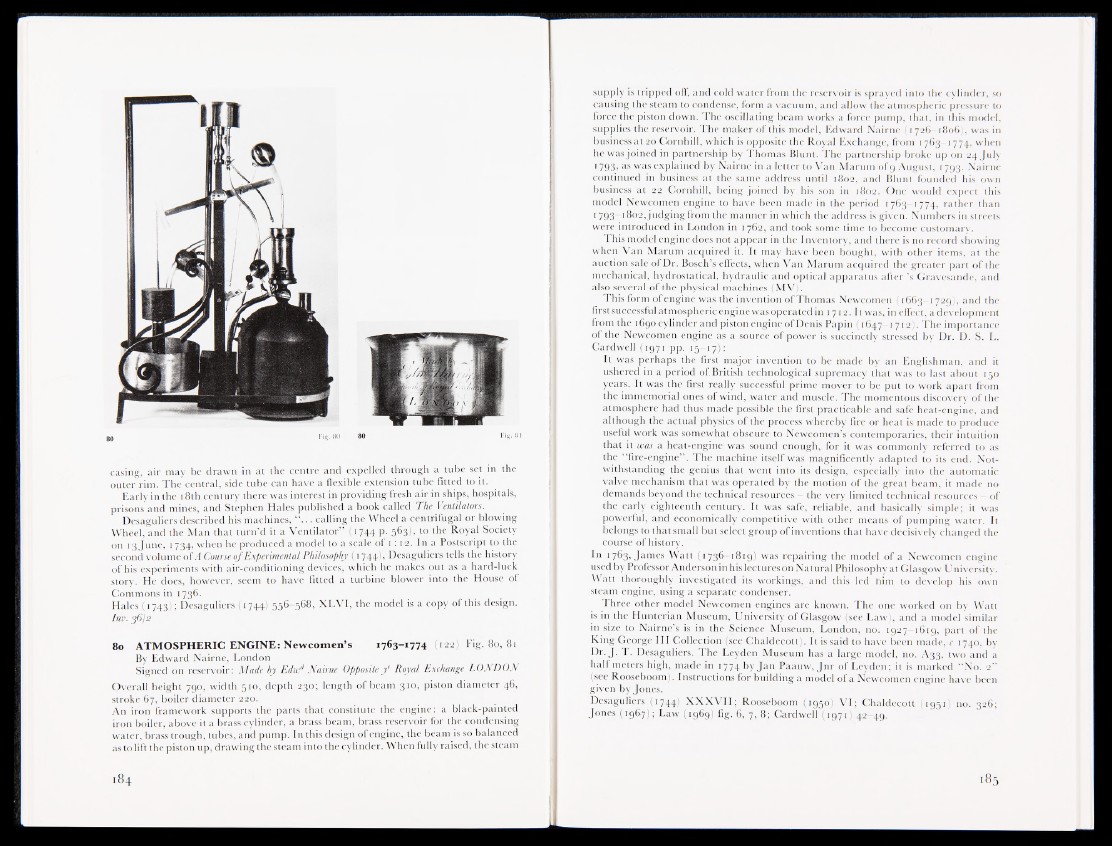

80 ATMOSPHERIC ENGINE: Newcomen’s 1763-1774 (122)1^.80,81

By Edward Nairne, London

Signed on reservoir: Made by Edwd Nairne Opposite f Royal Exchange LONDON

Overall height 790, width 510, depth 230; length of beam 310, piston diameter 46,

stroke 67, boiler diameter 220.

An iron framework supports the parts that constitute the engine: a‘i>lack-painted

iron boiler, above it a brass cylinder, a brass beam, brass reservoir for the condensing

water, brass trough, tubes, and pump. In this design of engine, the beam is so balanced

as to lift the piston up, drawing the steam into the cylinder. When fully raised, the steam

supply is tripped off, and cold water from the reservoir is sprayed into the cylinder, so

causing the steam to condense, form a vacuum, and allow the atmospheric pressure to

force the piston down. The oscillating beam works a force pump, that, in this model,

supplies the reservoir. The maker of this model, Edward Nairne (1726—1806), was in

business at 20 Cornhill, which is opposite the Royal Exchange, from 1763—1774, when

he was joined in partnership by Thomas Blunt. The partnership broke up on 24 July

1793, as was explained by Nairne in a letter to Van Marum of 9 August, t 793. Nairne

continued in business at the same address until 1802, and Blunt founded his own

business at 22 Cornhill, being joined by his son in 1802. One would expect this

model Newcomen engine to have been made in the period 1763-1774, rather than

1793-1802, judging from the manner in which the address is given. Numbers in streets

were introduced in London in 1762, and took some time to become customary.

This model engine does not appear in the Inventory, and there is no record showing

when Van Marum acquired it. It may have been bought, with other items, at the

auction sale of Dr. Bosch’s effects, when Van Marum acquired the greater part of the

mechanical, hydrostatical, hydraulic and optical apparatus after’s Gravcsandc, and

also several of the physical machines (MV).

This form of engine was the invention of Thomas Newcomen (1663—1729), and the

first successful atmospheric engine was operated in 1712. It was, in effect, a development

from the 1690 cylinder and piston engine of Denis Papin (1647-1712). The importance

of the Newcomen engine as a source of power is succinctly stressed by Dr. D. S. L.

Cardwell (1971 pp. 15-17):

It was perhaps the first major invention to be made by an Englishman, and it

ushered in a period of.British technological supremacy that was to last about 150

years. It was the first really successful prime mover to be put to work apart from

the immemorial ones of wind, water and muscle. The momentous discovery of the

atmosphere had thus made possible the first practicable and safe heat-engine, and

although the actual physics of the process whereby fire or heat is made to produce

useful work was somewhat obscure to Newcomen’s contemporaries, their intuition

that it was a heat-engine was sound enough, for it was commonly referred to as

the “ fire-engine” . The machine itself was magnificently adapted to its end. Notwithstanding

the genius that went into its design, especially into the automatic

valve mechanism that was operated by the motion of the great beam, it made no

demands beyond the technical resources — the very limited technical resources — of

the early eighteenth century. It was safe, reliable, and basically simple; it was

powerful, and economically competitive with other means of pumping water. It

belongs to that small but select group of inventions that have decisively changed the

course of history.

In 1763, James Watt (1736—1819) was repairing the model of a Newcomen engine

used by Professor Anderson in his lectures on Natural Philosophy at Glasgow University.

Watt thoroughly investigated its workings, and this led liim to develop his own

steam engine, using a separate condenser.

Three other model Newcomen engines are known. The one worked on by Watt

is in the Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow (see Law), and a model similar

in size to Nairne’s is in the Science Museum, London, no. 1927—1619, part of the

King George III Collectionjsee Chaldecott). It is said to have been made, c 1740, by

Dr. J. T. Desaguliers. The Leyden Museum has a large model, no. A33, two and a

half meters high, made in 1774 by Jan Paauw, Jnr of Leyden; it is marked “No. 2”

(see Rooseboom), Instructions for building a model of a Newcomen engine have been

given by Jones.

Desaguliers (1744) XXXVII; Rooseboom (1950) VI; Chaldecott (1951) no. 326;

Jones (1967); Law (1969) fig. 6, 7, 8; Cardwell (1971) 42—49.