stead of two. According to William Nicholson (1753-1815), writing in his Journal in

1 797? he was lent by Mr. Partington, in December 1787, “ an instrument contrived

by Dr. Darwin, and consisting of four metal plates... with wheel work” . This was

a mechanical version of Cavallo’s doubler, and Nicholson improved on it by putting

one disk on a cranked shaft, the other two being fixed; a description was read on

5 June, 1788, and printed the same year in the Philosophical Transactions. It is often

figured in encyclopaedias and text books of the period, and George Adams

(1750_I 795) produced it for sale at three guineas. The next piece of equipment of

concern here, is Cavallo’s “ collector of electricity” , the subject of a paper read on

10 April, 1788, and published later that year by the Royal Society. This was another

adaptation of Volta’s condenser, now to increase the charge collected on a

large rectangular plate from atmospheric electricity. Cavallo then made an ingenious

invention that tried to overcome some inherent weaknesses of earlier devices (e.g.

self electrification), and that would collect a charge and then allow a very considerable

accumulation of a charge of opposite sign, which could readily be measured.

This instrument is the “multiplier of electricity” , and it was explained in the third

edition of Cavallo’s Treatise, in the third volume printed in 1795.

All the above instruments are well known, even if some are infrequently found

in museums. But there is one instrument of this category that is unique, and it is to

be found in Teyler’s Museum. This is Nicholson’s “ spinning instrument” , and because

of its uniqueness, the inventor’s own description of it is given below. Presumably

between May 1787, when Bonnet’s paper was read, and December, when

Nicholson got hold of Darwin’s mechanical instrument, the spinner was designed, if

the account written seven years later is correct. It goes as follows (1797a p. 16-17):

In the year 1787 when the electrical doubler engaged the attention of philosophers...

I had the pleasure of a conversation with the Reverend Abraham Bennet of

YVirksworth, the inventor,... and [he] convinced me of the full value of his invention.

I then mentioned my intention to construct an instrument on that principle,

which soon afterwards I did. It was shown to Sir Joseph Banks and his friends, at

his house, nearly at the same time, and in the same year transferred to the celebrated

Mr. van Marum of Harlem, who now possesses it. From various other

avocations, I was prevented from causing any others to be made. It is not therefore

wonderful that the same thought should since have occurred to so great a

master of the subject as M. Cavallo, who in the third volume of his Electricity,

published in 1795, gives a description and engravings of an instrument very

different in form, but the same in principle.

Adams sent on 17 December, 1790, "Mr. Nicholson’s new instrument £ 2-10-0” ,

which is most probably the spinner, because he had already sent in the June

‘Nicholson’s doubler £ 3"3"0” * If this he so, then Nicholson’s remembrance of dates

is somewhat out.

Cavallo hotly denied any similarity in principle between his multiplier and the

spinner in a letter that he demanded be published in Nicholson’s Journal. It was, and

to it Nicholson added an extensive, and historically useful, account of the

instruments then available for detecting very small amounts of electricity^H'These

are: the condenser, the simple doubler, the doubler with mechanism, two instruments

by Mr. Cavallo, and the instrument described at p. 17 of this Journal” - the

spinner.

The full titles and reference to the inventors’ papers mentioned above are given

in the Bibliography. For further information on the devices the following works may

be consulted, but occasionally the authors have become a little confused between

instruments: Nicholson (1797b) esp. 395-399; Walker (1936); Utrecht (1967) 36-40;

Hackmann (1970); (L & Wiii 1971b).

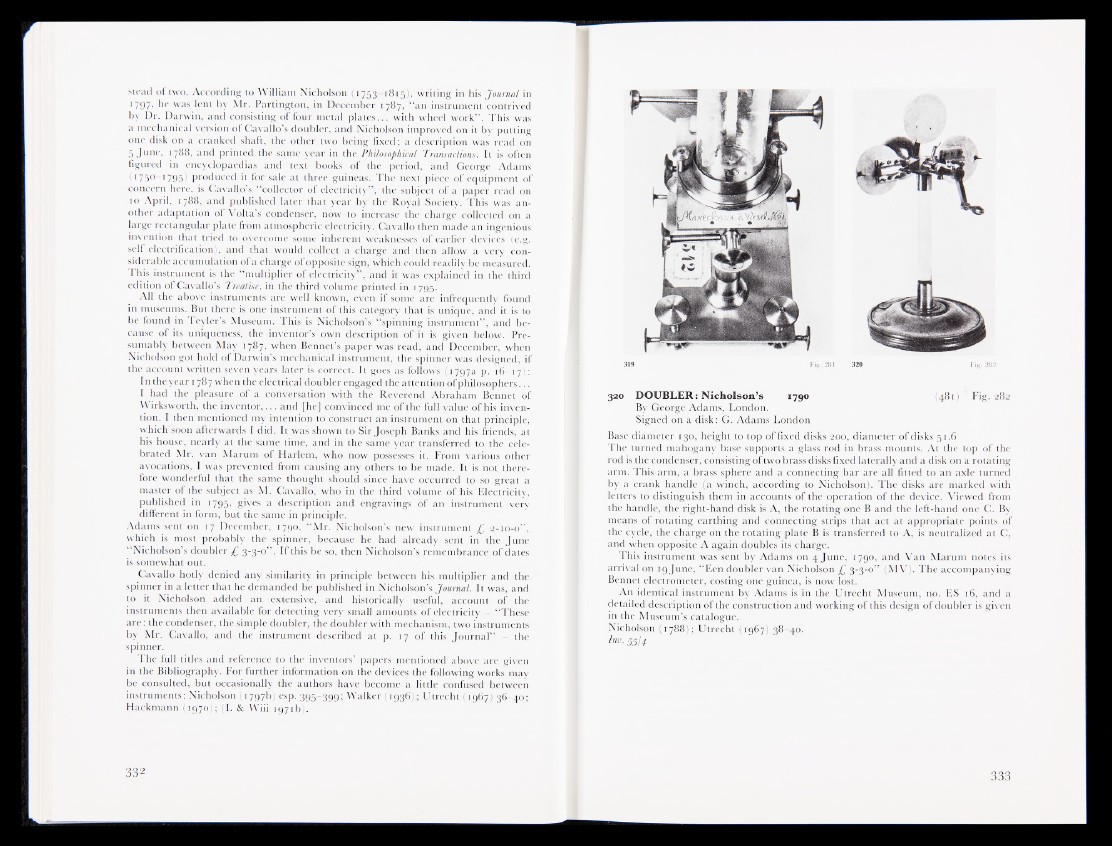

319 Kii>\ 281 320 282

320 DOUBLER: Nicholson’s *79° (481) Fig. 282

By George Adams, London.

Signed on a disk: G. Adams London

Base diameter 130, height to top of fixed disks 200, diameter of disks 51.6

The turned mahogany base supports a glass rod in brass mounts. At the top of the

rod is the condenser, consisting of two brass disks fixed laterally and a disk on a rotating

arm. This arm, a brass, sphere and a connecting bar are all fitted to an axle turned

by a crank handle (a winch, according to Nicholson). The disks are marked with

letters to distinguish them in accounts of the operation of the device. Viewed from

the handle, the right-hand disk is A, the rotating one B and the left-hand one C. By

means of rotating earthing and connecting strips that act at appropriate points of

the cycle, the charge on the rotating plate B is transferred to A, is neutralized at C,

and when opposite A again doubles its charge.

This instrument was sent by Adams on 4 June, 1790, and Van Marum notes its

arrival on 19 June, “Een doubler van Nicholson £ 3-3-0” (MV). The accompanying

Bennet electrometer, costing one guinea, is now lost.

An identical instrument by Adams is in the Utrecht Museum, no. ES 16, and a

detailed description of the construction and working of this design of doubler is given

in the Museum’s catalogue.

Nicholson (1788); Utrecht (1967) 38-40.

B 55t4