part of the trachea, and from thence passing forward, are

attached to the anterior part of the tongue, and by their contraction

bring the tongue back-again. The tongue itself is

furnished at the tip with a horny point, and also with four Or

five short bristle-like hairs on each side which are directed

backwards. At each side of the head of the bird, behind and

below the- external orifice of the ear, is a large and elongated

parotid gland, from which a membranous duct passes as fat

forwards as the point of union of the two bones, forming

together the lower mandible, on the inner surface of which

the glutinous secretion of these large glands passes, out, and

may be seen to issue on making slight pressure along the Course

of the glands. The flattened inner surface of the twa bones

which are united along thé distal part of their lower edgé,

forms the natural situation of the tongue when- at rost Vfithiri

the mandibles; and every time dt is drawn into the mouth

when the bird is feeding, it becomes covered with a fresh

supply of the glutinous mucus. From a close- examination

of the contents of the stomach of many Green Woodpeckers,

I am induced to believe that the point -of the tongue is not

used as a spear, nor the food taken up by the beak, unless

the subject, whatever it may happen to be, is too heavy, to be

lifted by adhesion.

Insects of various sorts,' ants, and their eggs, form the

principal food of the Green Woodpecker; and I have, seldom

had an opportunity of examining a recently killed specimen

the beak of which did not indicate, by the earth adhering to

the base, and to-the feathers about the nostrils, that the bird

had been at work at an ant-hill, and this species is therefore

more frequently seen on the ground than any other of our

Woodpeckers% it is said also to be a great enemy to bees..

Bechstein says that the Green Woodpecker will crack nuts. .

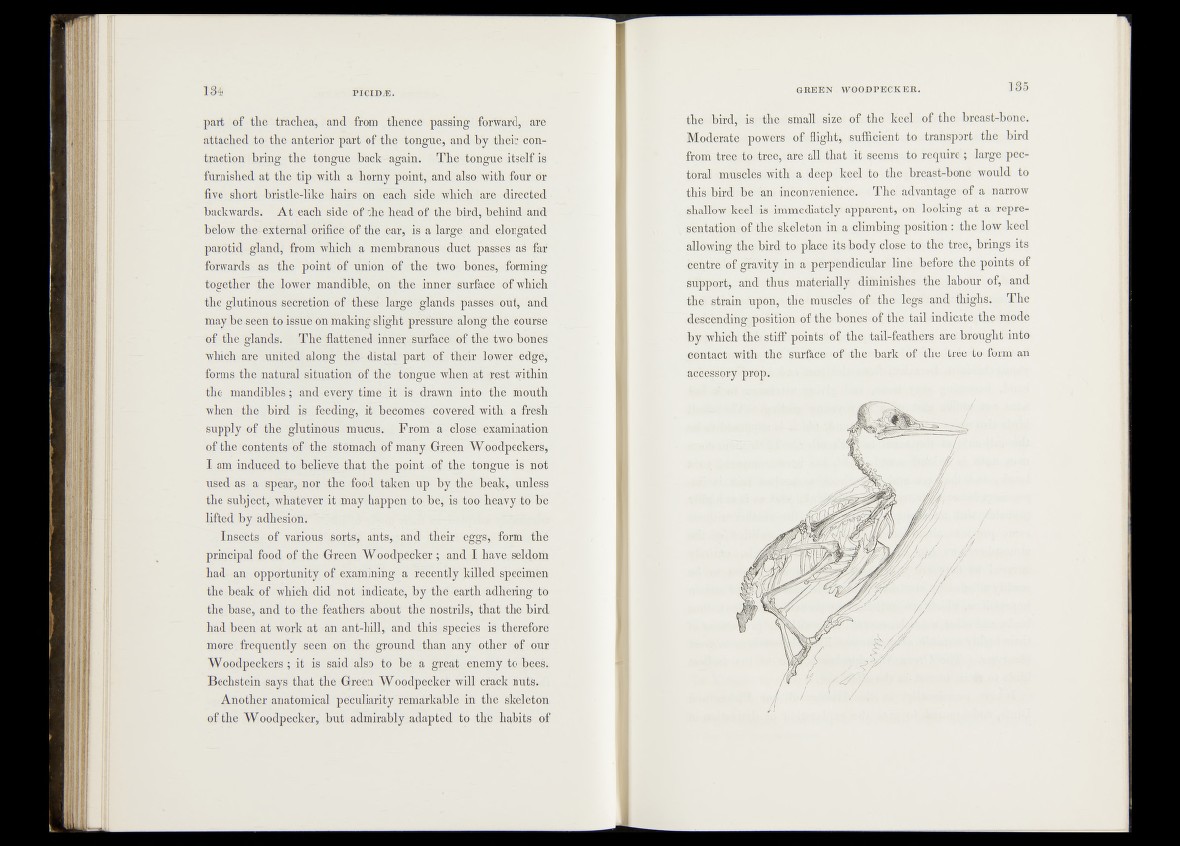

Another anatomical peculiarity remarkable in the skeleton

of the Woodpecker, but admirably adapted to the habits of

the bird, is the small size of the keel of the breast-bone.

Moderate powers of flight, sufficient to transport the bird

from tree to tree, are all that it seems to require ; large pectoral

muscles with a deep keel to the breast-bone would to

this bird be an inconvenience. The advantage of a narrow

shallow keel is immediately apparent, on looking at a representation

of the skeleton in a climbing position: the low keel

allowing the bird to place its body close to the tree, brings its

centre of gravity in a perpendicular line before the points of

support, and thus materially diminishes the labour of, and

the strain upon,-the muscles of the legs and thighs. The

descending .position of the bones ot the tail indicate the mode

by which the stiff points' of the tail-feathers are brought into

contact with the surface of the bark of the tree to form an

accessory prop.