often, before they can fly, larger than their parents. Two

young ones are usually the number-in a nest, but I have seen

three, The old birds are exceedingly attached to their offspring

; and, if any one approach near the nest, they make a

loud and drumming noise above the head, as if to' divert the

attention of-the intruder.”

Mr. Salmon, who, with his brother, passed three weeks in

the Orkneys in the summer of 1881, observes, jgfl We found the

Snipe in abundance in every island wherever there was the

least moisture; and their nests,« in general, Were placed*

among the long‘ grass, by theside o f the small lochs, and

amid the long heather that grows upon‘the sides of the hills.”

Mr. Hewitsoh met with several nests upon Foula, the most

westerly Qf the Shetland Islands,, among the dry heath on the

side of a steep hill, and at an elevation of not less- than from-

5t)0 to 1000 feet above the marshy plain.

Before tracing the Snipe into' other countries, I may notice

that the nest is very slight, Consisting only of a few bits of

dead grass, or dry herbage, , collected in a-depression on the

ground, and sometimes upon, or under the side of a tuffr of

grass or bunch of rushes. The eggs, four in number, of a

pale yellowish-or greenish white, the larger end spotted with

two or three shades of brown; these markings are rather

elongated, and disposed somewhat obliquely in reference; to>

the long axis of the egg; the length'of the egg about one

inch six lines, by one inch one line in breadth. The feeding

ground of the Snipe is by the sides of land springs, or in-

water meadows j and in low flat countries they are frequently

found among wet turnips. A writer in the Magazine of

Natural History, describing their mode of feeding, as observed

by himself with a powerful telescope, says, “ I distinctly

saw them pushing their bills into the thin “mud, by

Repeated thrusts, quite up to the base, drawing them back

with great quickness, and every now and then shifting their

ground a little.” The holes made with their bills, when thus

searching for food, are easil ƒ traced. In my own communication

on the»' subject-of Snipes, published in Mr. Loudon’s

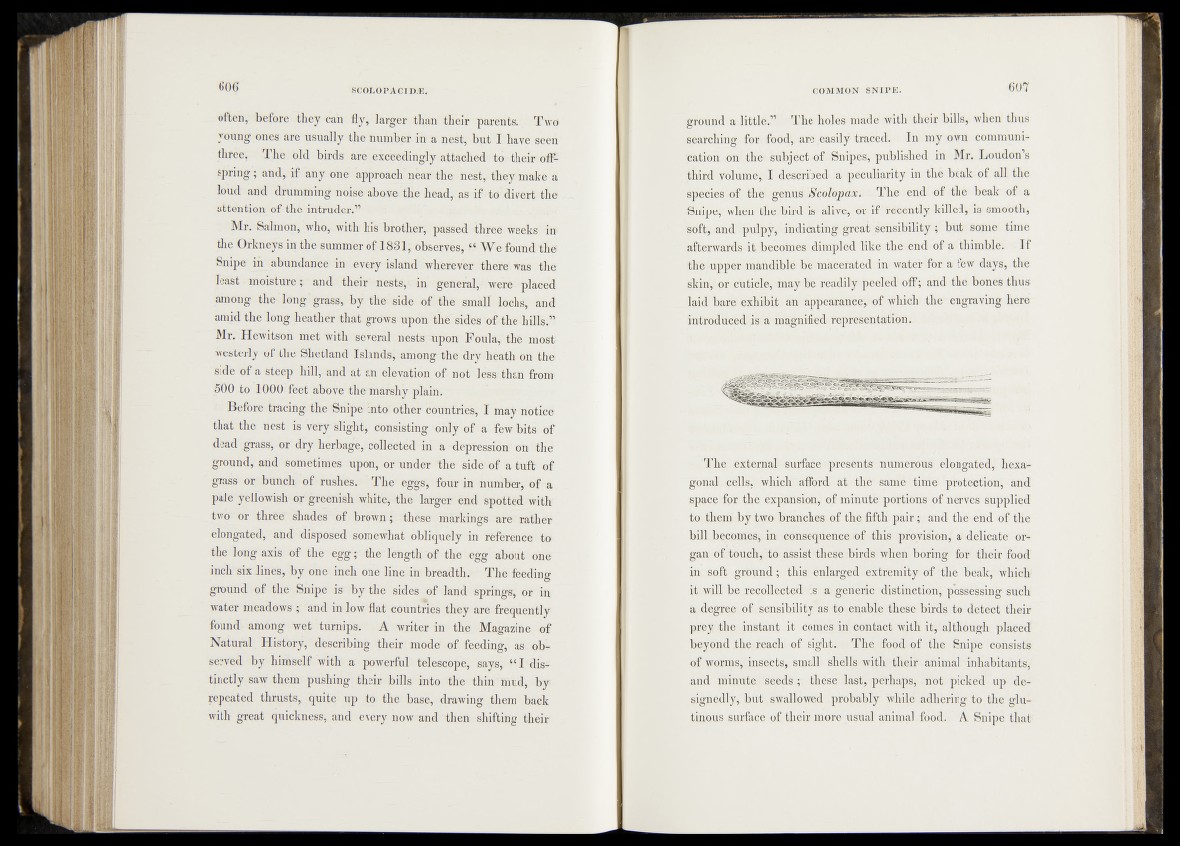

third volume, I described a «peculiarity in the beak of all the

species of the genus Scolopax. The end of thé beak of a

Snipe, when the bird1'is alive, or if recently killed, is smooth,

soft, and pulpy," indicating great sensibility-■$ but some time

afterwards itjbecomes.» dimpled like the-end of a thimble. If

the upper mandible be macerated in water for a few days, the

skin,, omouticle, maybe readily peeled off;! and the bones thus

iaid bare exhibit- an appearance,*of which* the"engraving here

introduced $ a magnified representation;. :

* The. external surface - presents' numerous elongated,*, hexa-

gonal ijcellsp/which' afford at the same-time protection, and

space for the expansion^ of minute portions "of nerves supplied

to them b y two branches #6 fifth pair * and the eUd of the

bill bqGomesy.in consequence «of this provision, a delicate organ

of jtouch,ito assist these birds when boring for their food

in ,*,soft ground; ■ this' enlarged.'extremity of the beak," which-

it will be recollected is a generic distinction^‘possessing such

& degree of Sensibility "asi to enable these birds to detect their

prey the instant it comes in contact with if,'although, placed-

beyond .the reach of sight..- The* food of the Snipe consists

of worms, -insects,. small shells with their animal 'inhabitants,'

and foinuteyseeds; these -last, perhaps, -not picked up de*

signedly, but swallowed .probably while adhering to the glutinous

surface bf. their more usual animal food.. A Snipe that