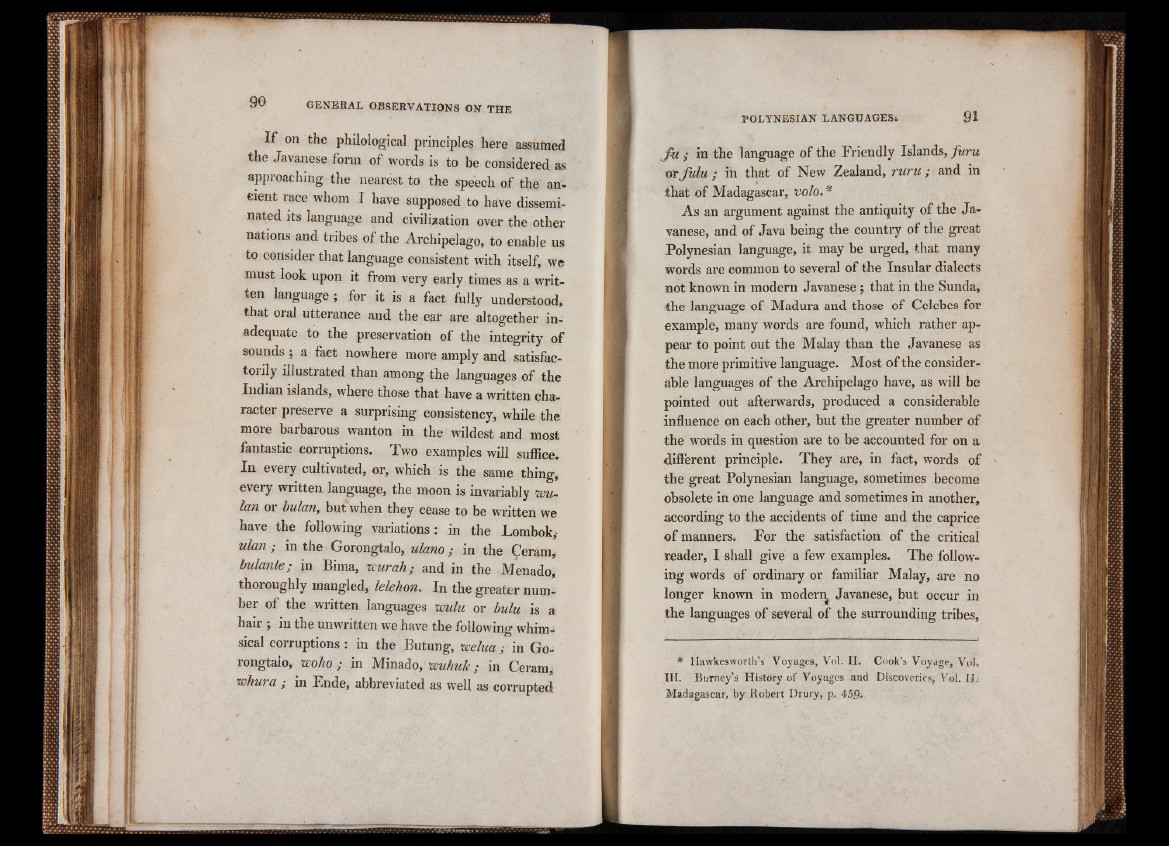

If on the philological principles here assumed

the Javanese form of words is to be considered as

approaching the nearest to the speech of the ancient

race whom I have supposed to have disseminated

its language and civilization over the other

nations and tribes of the Archipelago, to enable us

to consider that language consistent with itself, we

must look upon it from very early times as a written

language; for it is a fact fully understood,

that oral utterance and the ear are altogether inadequate

to the preservation of the integrity of

sounds ; a fact nowhere more amply and satisfactorily

illustrated than among the languages of the

Indian islands, where those that have a written character

preserve a surprising consistency, while the

more barbarous wanton in the wildest and most

fantastic corruptions. Two examples will suffice.

In every cultivated, or, which is the same thing,

every written language, the moon is invariably <wu-

lan or bulan, but when they cease to be written we

have the following variations: in the Lombok,

ulan ; in the Gorongtalo, ulano; in the Ceram,

bulante; in Bima, a-urah; and in the Menado>

thoroughly mangled, lelehon. In the greater number

of the written languages >wulu or bulu is a

hair ; in the unwritten we have the following whimsical

corruptions: in the Butung, welua j in Gorongtalo,

woho ; in Minado, wuhuk; in Ceram,-

whura ; in Ende, abbreviated as well as corrupted

fu ; in the language of the Friendly Islands, furu

or fulu ,* ih that of New Zealand, tutu ; and in

that of Madagascar, volo. *

As an argument against the antiquity of the Javanese,

and of Java being the country of the great

Polynesian language, it may be urged, that many

words are common to several of the Insular dialects

not known in modern Javanese ; that in the Sunda,

the language of Madura and those of Celebes for

example, many words are found, which rather appear

to point out the Malay than the Javanese as

the more primitive language. Most of the considerable

languages of the Archipelago have, as will be

pointed out afterwards, produced a considerable

influence on each other, but the greater number of

the words in question are to be accounted for on a

different principle. They are, in fact, words of

the great Polynesian language, sometimes become

obsolete in one language and sometimes in another,

according to the accidents of time and the caprice

of manners. For the satisfaction of the critical

reader, I shall give a few examples. The following

words of ordinary or familiar Malay, are no

longer known in modern Javanese, but occur in

the languages of several of the surrounding tribes,

* Hawkesworth’s Voyages, Vol. II. Cook’s Voyage, Vol.

III. Burney’s History of Voyages and Discoveries, VoL ID

Madagascar, by Robert Drury, p. 459.