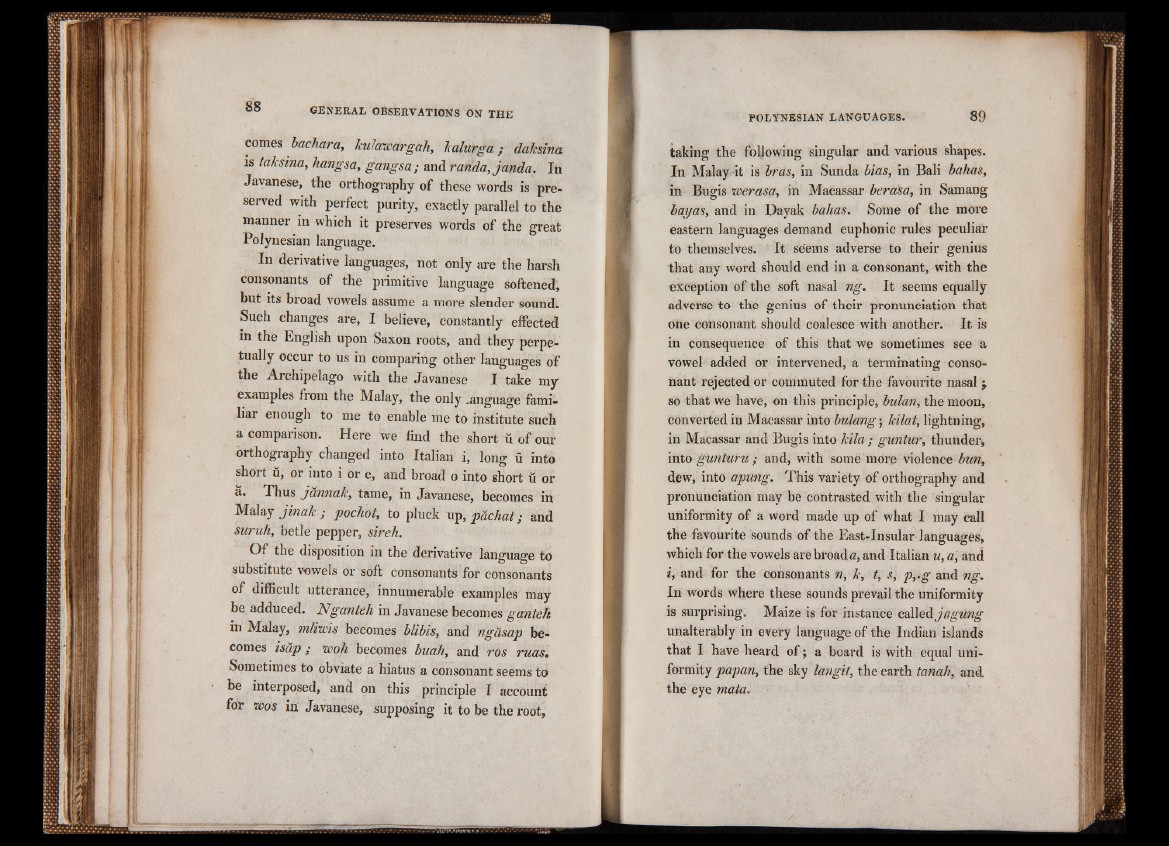

comes backara, huloewargah, Icalurga ; dalcsina

is taksina, hangsa, gangsa ; andranda,janda. Iii

Javanese, the orthography of these words is preserved

with perfect purity, exactly parallel to the

manner in which it preserves words of the great

Polynesian language.

In derivative languages, not only are the harsh

consonants of the primitive language softened,

but its broad vowels assume a more slender sound.

Such changes are, I believe, constantly effected

^he English upon Saxon roots, and they perpetually

occur to us in comparing other languages of*

the Archipelago with the Javanese I take my

examples from the Malay, the only ^.anguage familiar

enough to me to enable me to institute such

a comparison. Here we find the short Ü of our

orthography changed into Italian i, long ü into

short ü, or into i or e, and broad o into short ü or

R* Thus j annale, tame, m Javanese, becomes in

Malay jinak ; pochot, to pluck up, pâchat ; and

suruh, betle pepper, sirek.

Of the disposition in the derivative language to

substitute vowels or soft consonants for consonants

of difficult utterance, innumerable examples may

be adduced. Nganteh in Javanese becomes ganteh

in Malay, mliwis becomes blibis, and ngasap becomes

isap ; tvoh becomes buah, and vos ruas.

Sometimes to obviate a hiatus a consonant seems to

be intei posed, and on this principle I account

for 'Wos in Javanese, supposing it to be the root,

taking the following singular and various shapes.

In Malay-it is bras, in Sunda bias, in Bali bahas,

in Bugis werasa, in Macassar berasa, in Samang

bayas, and in IJayak bahas. Some of the more

eastern languages demand euphonic rules peculiar

to themselves. It seems adverse to their genius

that any word should end in a consonant, with the

exception of the soft nasal ng. It seems equally

adverse to the genius of their pronunciation that

one consonant should coalesce with another. It is

in consequence of this that we sometimes see a

vowel added or intervened, a terminating consonant

rejected or commuted for the favourite nasal j

so that we have, on this principle, bulan, the moon,

converted in Macassar into bulang ; Jcilat, lightning,

in Macassar and Bugis into kila ; guntur, thunder^

into gunturu ; and, with some more violence bun,

dew, into apung. This variety of orthography and

pronunciation may be contrasted with the singular

uniformity of a word made up of what I may call

the favourite sounds of the East-Insular languages,

which for the vowels are broad a, and Italian u, a, and

i, and for the consonants n, k, t, S, p,.g and ng.

In words where these sounds prevail the uniformity

is surprising. Maize is for instance called jagung

unalterably in every language of the Indian islands

that I have heard of ; a board is with equal uniformity

pagan, the sky langit, the earth tanah, and

the eye mata.