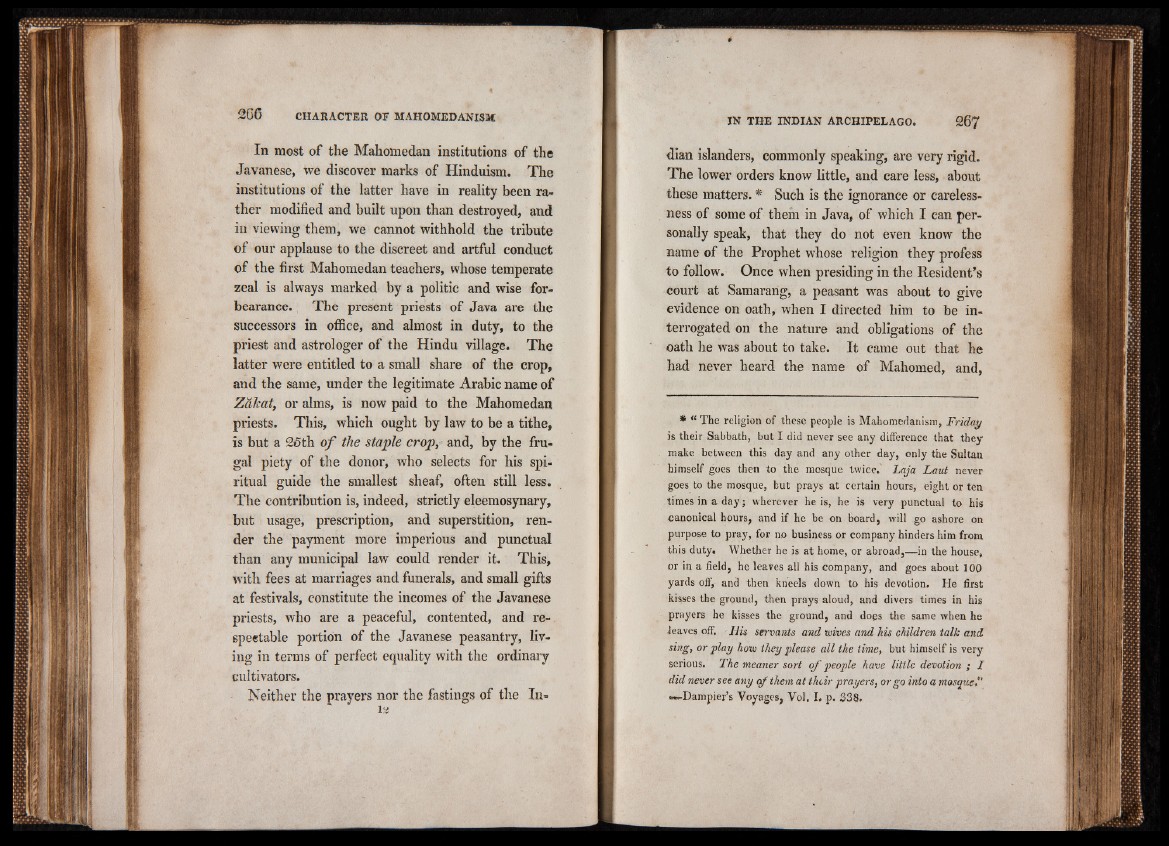

In most of the Mahomedan institutions of the

Javanese, we discover marks of Hinduism. The

institutions of the latter have in reality been rather

modified and built upon than destroyed, and

in viewing them, we cannot withhold the tribute

of our applause to the discreet and artful conduct

of the first Mahomedan teachers, whose temperate

zeal is always marked by a politic and wise forbearance.

The present priests of Java are the

successors in office, and almost in duty, to the

priest and astrologer of the Hindu village. The

latter were entitled to a small share of the crop,

and the same, under the legitimate Arabic name of

Z c ika ty or alms, is now paid to the Mahomedan

priests. This, which ought by law to be a tithe,

is but a 25th o f the staple crop, and, by the frugal

piety of the donor, who selects for his spiritual

guide the smallest sheaf, often still less.

The contribution is, indeed, strictly eleemosynary,

but usage, prescription, and superstition, render

the payment more imperious and punctual

than any municipal law could render it. This,

with fees at marriages and funerals, and small gifts

at festivals, constitute the incomes of the Javanese

priests, who are a peaceful, contented, and respectable

portion of the Javanese peasantry, living

in terms of perfect equality with the ordinary

cultivators.

Neither the prayers nor the is fastings of the Indian

islanders, commonly speaking, are very rigid.

The lower orders know little, and care less, about

these matters. * Such is the ignorance or carelessness

of some of them in Java, of which I can personally

speak, that they do not even know the

name of the Prophet whose religion they profess

to follow. Once when presiding in the Resident’s

court at Samararig, a peasant was about to give

evidence on oath, when I directed him to be interrogated

on the nature and obligations of the

oath he was about to take. It came out that he

had never heard the name of Mahomed, and,

* “ The religion of these people is Mahomedanism, Friday

is their Sabbath, but I did never see any difference that they

make between this day and any other day, only the Sultan

himself goes then to the mosque twice.' Laja Laut never

goes to the mosque, but prays at certain hours, eight or ten

times in a day; where ver he is, he is very punctual to his

canonical hours, and if he be on board, will go ashore on

purpose to pray, for no business or company hinders him from

this duty. Whether he is at home, or abroad,—in the house,

or in a field, he leaves all his company, and goes about 100

yards off,- and then kneels down to his devotion. He first

kisses the ground, then prays aloud, and divers times in his

prayers he kisses the ground, and dogs the same when he

leaves off. His servants and tvives and his children talk and

sing, or play hole they please all the time, but himself is very

serious. The meaner sort o f people have little devotion ; I

did never see any of them at their prayers, or go into a mosque,"

-wDampier’s Voyages, Vol. I. p. 333.