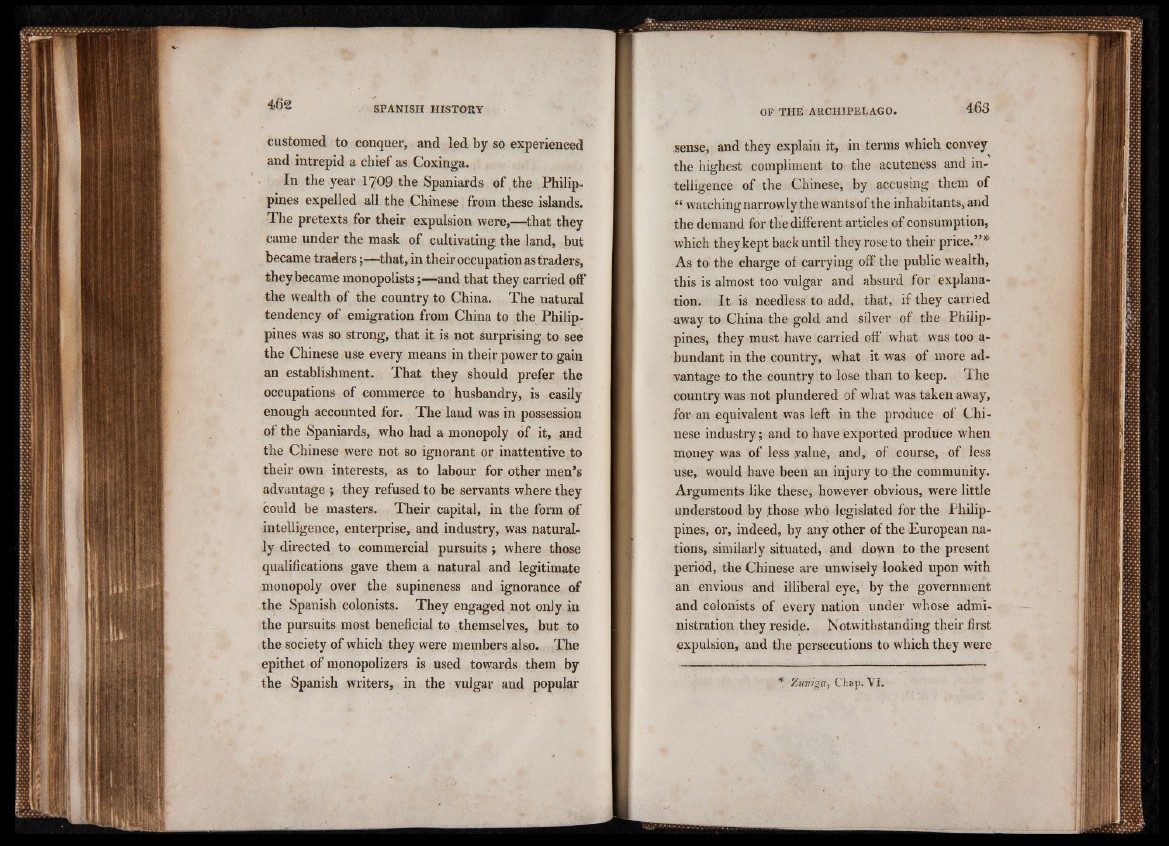

customed to conquer, and led by so experienced

and intrepid a chief as Coxinga.

In the year 1709 the Spaniards of the Philip-

pines expelled all the Chinese from these islands.

The pretexts for their expulsion were,—that they

came under the mask of cultivating the land, but

became traders j—that, in their occupation as traders,

they became monopolists ;—and that they carried off

the wealth of the country to China. The natural

tendency of emigration from China to the Philip,

pines was so strong, that it is not surprising to see

the Chinese use every means in their power to gain

an establishment. That they should prefer the

occupations of commerce to husbandry, is easily

enough accounted for. The land was in possession

of the Spaniards, who had a monopoly of it, and

the Chinese were not so ignorant or inattentive to

their own interests, as to labour for other men’s

advantage ; they refused to be servants where they

could be masters. Their capital, in the form of

intelligence, enterprise, and industry, was naturally

directed to commercial pursuits j where those

qualifications gave them a natural and legitimate

monopoly over the supineness and ignorance of

the Spanish colonists. They engaged not only in

the pursuits most beneficial to themselves, but to

the society of which they were members also. The

epithet of monopolizers is used towards them by

the Spanish writers, in the vulgar and popular

sense, and they explain it, in terms which convey

the highest compliment to the acuteness and intelligence

of the Chinese, by accusing them of

ff watching narrowly the wants of the inhabitants, and

the demand for the different articles of consumption,

which they kept back until they rose to their price.” *

As to the charge of carrying off the public wealth,

this is almost too vulgar and absurd for explanation.

It is needless to add, that, if they carried

away to China the gold and silver of the Philippines,

they must have carried off what was too a-

bundant in the country, what it was of more advantage

to the country to lose than to keep. The

country was not plundered of what was taken away,

for an equivalent was left in the produce of Chinese

industry ; and to have exported produce when

money was of less value, and, of course, of less

use, would have been an injury to the community.

Arguments like these, however obvious, were little

understood by those who legislated for the Philippines,

or, indeed, by any other of the European nations,

similarly situated, and down to the present

period, the Chinese are unwisely looked upon with

an envious and illiberal eye, by the government

and colonists of every nation under whose administration

they reside. Notwithstanding their first

expulsion, and the persecutions to which they were

* Zuniga, Chap. VI.