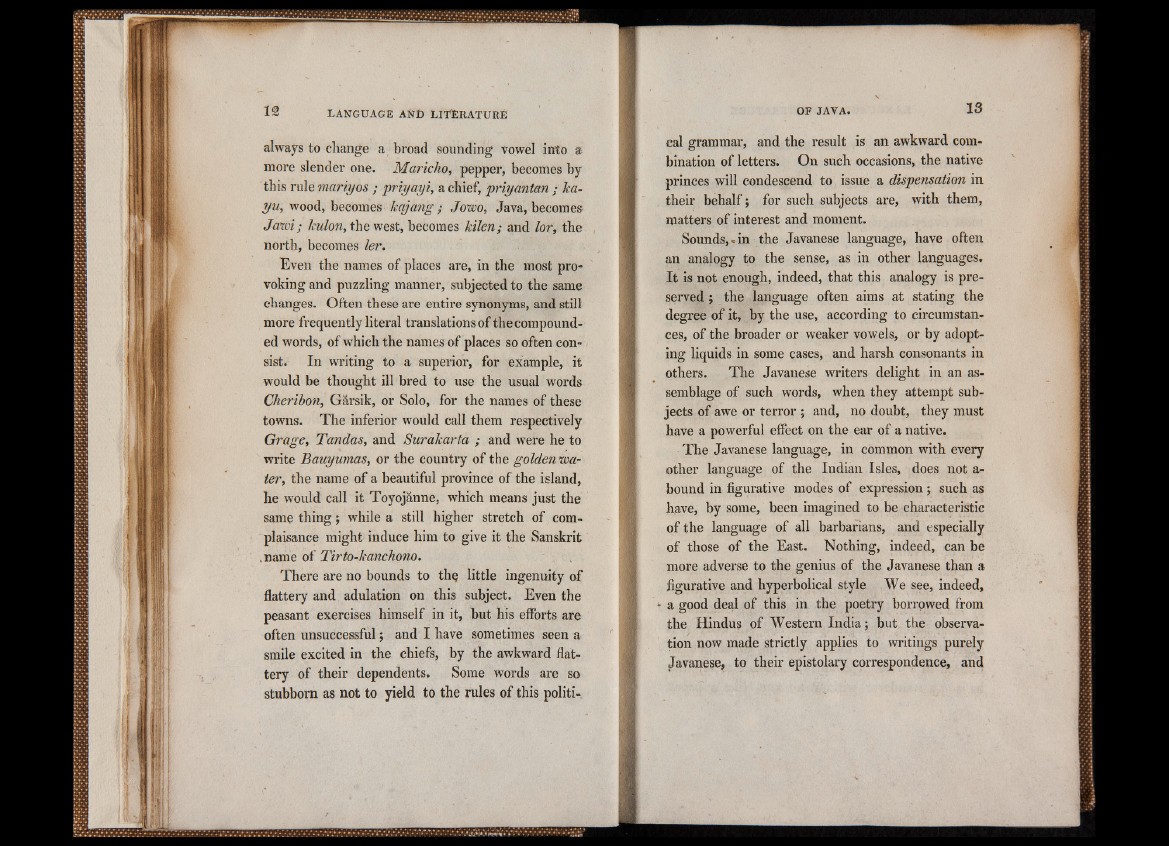

always to change a broad sounding towel into a

more slender one. Maricho, pepper, becomes by

this rule mariyos ; priyayi, a chief, priyantan ; ka-

yu, wood, becomes kajang; Jowo, Java, becomes

Jawi; kulon, the west, becomes kilen; and lor, the

north, becomes ler.

Even the names of places are, in the most provoking

and puzzling manner, subjected to the same

changes. Often these are entire synonyms, and still

more frequently literal translations of the compounded

words, of which the names of places so often consist.

In writing to a superior, for example, it

would be thought ill bred to use the usual words

Cheribon, Garsik, or Solo, for the names of these

towns. The inferior would call them respectively

Grage, Tandas, and Surakarta ; and were he to

write Bauyumas, or the country of the golden water,

the name of a beautiful province of the island,

he would call it Toyojanne, which means just the

same thing; while a still higher stretch of complaisance

might induce him to give it the Sanskrit

.name of Tirto-kanchono.

There are no bounds to thq little ingenuity of

flattery and adulation on this subject. Even the

peasant exercises himself in it, but his efforts are

often unsuccessful; and I have sometimes seen a

smile excited in the chiefs, by the awkward flattery

of their dependents. Some words are so

stubborn as not to yield to the rules of this political

grammar, and the result is an awkward combination

of letters. On such occasions, the native

princes will condescend to issue a dispensation in

their behalf; for such subjects are, with them,

matters of interest and moment.

Sounds,-in the Javanese language, have often

an analogy to the sense, as in other languages.

It is not enough, indeed, that this analogy is preserved

; the language often aims at stating the

degree of it, by the use, according to circumstances,

of the broader or weaker vowels, or by adopting

liquids in some cases, and harsh consonants in

others. The Javanese writers delight in an assemblage

of such words, when they attempt subjects

of awe or terror ; and, no doubt, they must

have a powerful effect on the ear of a native.

The Javanese language, in common with every

other language of the Indian Isles, does not a-

bound in figurative modes of expression; such as

have, by some, been imagined to be characteristic

of the language of all barbarians, and especially

of those of the East. Nothing, indeed, can be

more adverse to the genius of the Javanese than a

figurative and hyperbolical style We see, indeed,

v a good deal of this in the poetry borrowed from

the Hindus of Western India; but the observation

now made strictly applies to writings purely

Javanese, to their epistolary correspondence, and