o f fine wood, not merely pines, which are common every where, but

oaks and other valuable hard woods.

Posting becomes more and more difficult as you approach the capital.

Unless you employ a forebod you are liable to be detained at every stage

several hours for horses. At one stage, indeed, quite in the neighbourhood

o f Stockholm, I was detained about thirteen hours. On Friday

morning, September the 4th, we had ordered horses at half past four, but

did not get them till half past six. Though our distance from Stockholm

did not exceed 33 English miles, yet, being detained at every stage, it was

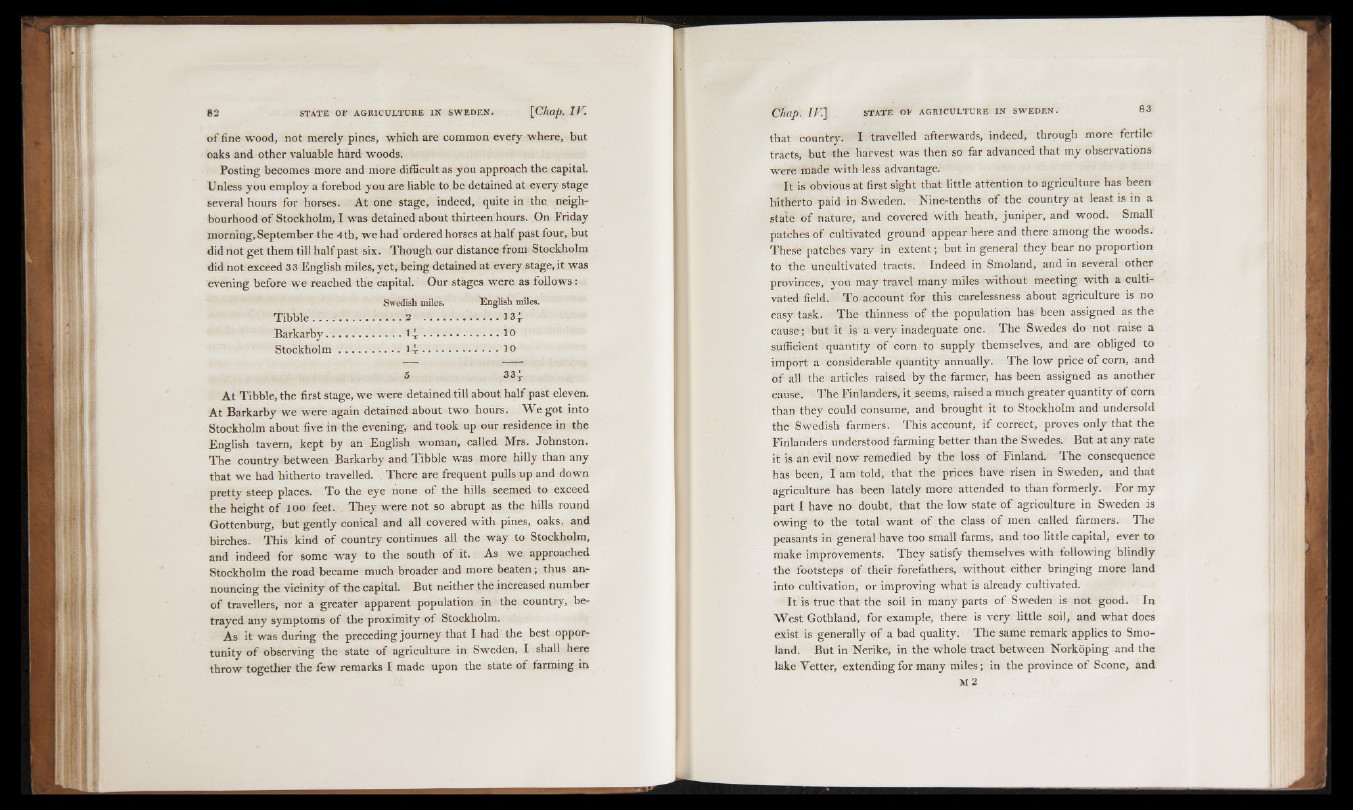

evening before we reached the capital. Our stages were as follows:

Swedisk miles. English miles.

T i b b i e . . . . . . . . . . 2 ............. .......... 134-

Barkarby........................ 1 4 ■ • * ..................... 10

Stockholm.................... 1 4 ...................... 10

5 334

A t Tibbie, the first stage, we were detained till about half past eleven.

At Barkarby we were again detained about two hours. We got into

Stockholm about five in the evening, and took up our residence in the

English tavern, kept by an English woman, called Mrs. Johnston.

The country between Barkarby and Tibbie was more hilly than any

that we had hitherto travelled. There are frequent pulls up and down

pretty steep places. To the eye none of the hills seemed to exceed

the height o f 100 feet. They were not so abrupt as the hills round

Gottenburg, but gently conical and all covered with pines, oaks, and

birches. This kind of country continues all the way to Stockholm,

and indeed for some way to the south o f it. As we approached

Stockholm the road became much broader and more beaten; thus announcing

the vicinity o f the capital. But neither the increased number

o f travellers, nor a greater apparent population in the country, betrayed

any symptoms o f the proximity o f Stockholm.

As it was during the preceding journey that I had the best opportunity

o f observing the state of agriculture in Sweden, I shall here

throw together the few remarks I made upon the state of farming in

that country. I travelled afterwards, indeed, through more fertile

tracts, but the harvest was then so far advanced that my observations

were made with less advantage.

It is obvious at first sight that little attention to agriculture has been

hitherto paid in Sweden. Nine-tenths of the country at least is in a

state of nature, and covered with heath, juniper, and wood. Small

patches of cultivated ground appear here and there among the woods.

These patches vary in extent; but in general they bear no proportion

to the uncultivated tracts. Indeed in Smoland, and in several other

provinces, you may travel many miles without meeting with a cultivated

field. To account for this carelessness about'agriculture is no

easy task. The thinness of the population has been assigned as the

cause; but it is a very inadequate one. The Swedes do not raise a

sufficient quantity o f corn to supply themselves, and are obliged to

import a considerable quantity annually. The low price o f corn, and

of all the articles raised by the farmer, has been assigned as another

cause. The Finlanders, it seems, raised a much greater quantity o f com

than they could consume, and brought it to Stockholm and undersold

the Swedish farmers. This account, i f correct, proves only that the

Finlanders understood farming better than the Swedes. But at any rate

it is an evil now remedied by the loss o f Finland. The consequence

has been, I am told, that the prices have risen in Sweden, and that

agriculture has been lately more attended to than formerly. For my

part I have no doubt, that the low state o f agriculture in Sweden is

owing to the total want of the class o f men called farmers. The

peasants in general have too small farms, and too little capital, ever to

make improvements. They satisfy themselves with following blindly

the footsteps of their forefathers, without either bringing more land

into cultivation, or improving what is already cultivated.

It is true that the soil in many parts o f Sweden is not good. In

West Gothland, for example, there is very little soil, and what does

exist is generally o f a bad quality. The same remark applies to Smoland.

But in Nerike, in the whole tract between Norkoping and the

lake Vetter, extending for many miles; in the province of Scone, and

m 2