they all paid a toll to the King of Denmark, as a compensation for the

light-houses which he kept up on his coasts. But since the war between

Great Britain and Denmark, these light-houses have been removed,

and the vessels now pass from the Cattegat into the Baltic,

through the Great Belt. Not that the Danes are able to prevent the

passage of the Sound, as was demonstrated by the passing o f the British

fleet in 1801; but the Great Belt, in consequence of its greater

breadth, has been found safer for merchant vessels sailing under

convoy.

From the Danish islands to the latitude o f Stockholm, the sea is

known by the name of the Baltic. It goes first in an easterly direction

as far as Memel, a length of about 3oo miles, with a mean breadth,

amounting to about 140 miles. It then proceeds in a northerly direction

from the north coast of Germany to fhe islands of Oland, a length

of about 350 miles, with a mean breadth of about 170 miles. At this

place it separates into two gulfs, the Gulf of Finland, which runs directly

east to Russia, and terminates at St. Petersburgh, constituting a

length of about 200 miles, with a mean breadth o f about 7° miles.

The Gulf of Bothnia runs north, nearly to the latitude of 66°, constituting

a length of nearly 350 miles, with a mean breadth o f about 100

miles. It is narrowest at Umea, where its breadth does not much exceed

40 miles.

The constituents of the Baltic differ materially, at least in point of

quantity, from those o f the Ocean. It is well known that the Ocean

consists of water, holding in solution a certain proportion o f the

following salts:

Common salt.

Muriate of magnesia.

Sulphate o f magnesia.

Sulphate o f lime.

Sulphate o f soda ?

The average quantity of all these salts held in solution by the waters

of the Ocean, amounts to about one twenty-seventh of the weight of

the water. That is to say, every twenty-seven grains o f sea-water

contain one grain of these salts in solution. But this is very far from

being the case with the water o f the Baltic. I took the specific gravity

o f the sea water of the Frith o f Forth, of water taken up at Tunaberg

on the coast of Sôdermanland, somewhat to the south o f Stockholm,

o f water taken up at the Sound, and o f water taken up off the Scaw

point. The following were the results obtained. The specific gravities

were taken at the temperature of 6o°.

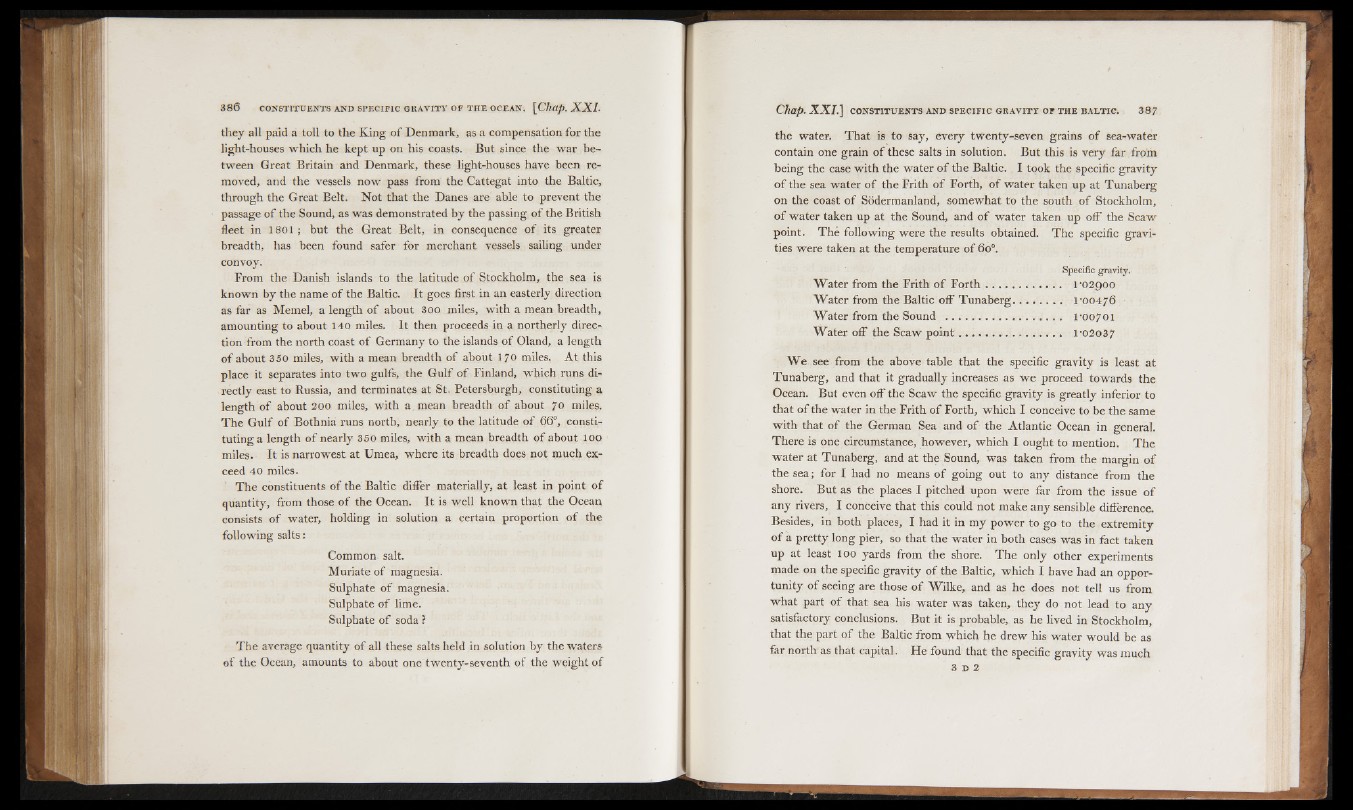

Specific gravity.

Water from the Frith of F orth ..... l '02900

Water from the Baltic off Tunaberg............ 1'00476

Water from the Sound ................................... i -oo7oi

Water off the Scaw point. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1'02037

We see from the above table that the specific gravity is least at

Tunaberg, and that it gradually increases as we proceed towards the

Ocean. But even off the Scaw the specific gravity is greatly inferior to

that o f the water in the Frith o f Forth, which I conceive to be the same

with that o f the German Sea and o f the Atlantic Ocean in general.

There is one circumstance, however, which I ought to mention. The

water at Tunaberg, and at the Sound, was taken from the margin o f

the sea; for I had no means o f going out to any distance from the

shore. But as the places I pitched upon were far from the issue o f

any rivers, I conceive that this could not make any sensible difference.

Besides, in both places, I had it in my power to go to the extremity

of à pretty long pier, so that the water in both cases was in fact taken

up at least 100 yards from the shore. The oniy other experiments

made on the specific gravity of the Baltic, which I have had an opportunity

o f seeing are those o f Wilke, and as he does not tell us from

what part of that sea his water was taken, they do not lead to any

satisfactory conclusions, But it is probable, as he lived in Stockholm,

that the part o f the Baltic from which he drew his water would be as

far north as that capital. He found that the specific gravity was much

3 d 2