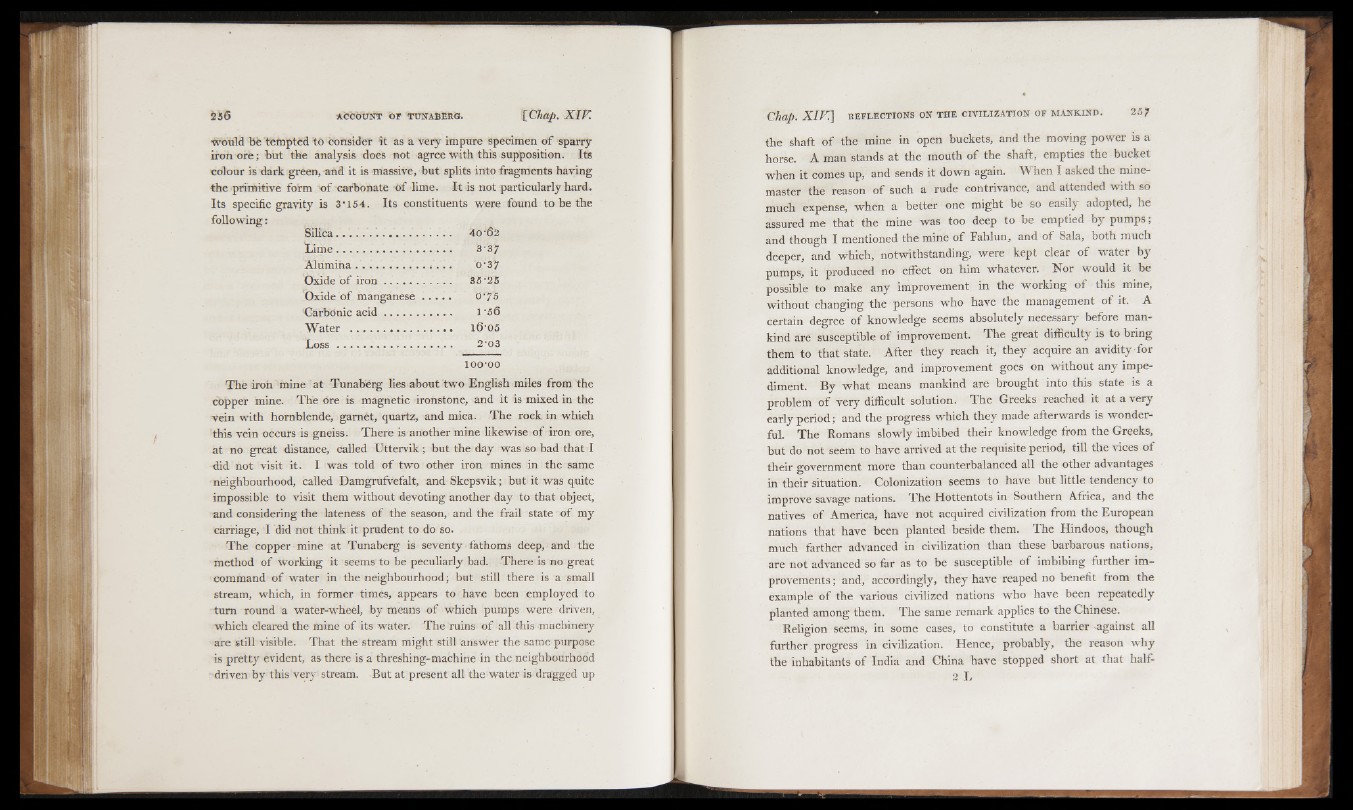

would be tempted to consider it as a very impure specimen of sparry

iron ore; but the analysis does not agree with this supposition. Its

colour is dark green, and it is massive, but splits into fragments having

the primitive form of carbonate of lime. It is not particularly hard.

Its specific gravity is 3 ' 15 4 . Its constituents were found to be the

following:

Silica ................ 40-62

l im e 3 -3?

Alumina.................. .... .-Vi. "0*37

Oxide o f iro n ...................... 35;25

Oxide of manganese O'75

'Carbonic a c id ...................... 1 '5 6

Water .......................... l 6-05

L o s s ......... 2-03

ioo-oo

The iron mine at Tunaberg lies about two English miles from the

copper mine. The ore is magnetic ironstone, and it is mixed in the

vein with hornblende, garnet, quartz, and mica. The rock in which

this vein occurs is gneiss. There is another mine likewise o f iron ore,

at no great distance, called Uttervik; but the day was so bad that I

did not visit it. I was told o f two other iron mines in thersame

neighbourhood, called Damgrufvefalt, and Skepsvik; but it was quite

impossible to visit them without devoting another day to that object,

and considering the lateness o f the season, and the frail state of my

carriage, I did not think it: prudent to do so.

The copper mine at Tunaberg is seventy fathoms deep, and the

method of working it seems to be peculiarly bad. There is no great

command of water in the neighbourhood; but still there is a small

stream, which, in former times, appears to have been employed to

turn round a water-wheel, by means of which pumps were driven,

which cleared the mine o f its water. The ruins o f all this machinery

are still visible. That the stream might still answer the same purpose

is pretty evident, as there is a threshing-machine in the neighbourhood

driven by this very stream. But at present all the water is dragged up

the shaft o f the mine in open buckets, and the moving power is a

horse. A man stands at the mouth o f the shaft, empties the bucket

when it comes up, and sends it down again. When I asked the mine-

master the reason o f such a rude contrivance, and attended with so

much expense, when a better one might be so easily adopted, he

assured me that the mine was too deep to be emptied by pumps;

and though I mentioned the mine o f Fahlun, and of Sala, both much

deeper, and which, notwithstanding, were kept clear of water by

pumps, it produced no effect on him whatever. Nor would it be

possible to make any improvement in the working o f this mine,

without changing the persons who have the management of it. A

certain degree of knowledge seems absolutely necessary before mankind

are susceptible of improvement. The great difficulty is to bring

them to that state. After they reach it, they acquire an avidity for

additional knowledge, and improvement goes on without any impediment.

By what means mankind are brought into this state is a

problem o f very difficult solution. The Greeks reached it at a very

early period; and the progress which they made afterwards is Wonderful.

The Romans slowly imbibed their knowledge from the Greeks,

but do not seem to have arrived at the requisite period, till the vices of

their government more than counterbalanced all the other advantages

in their situation. Colonization seems to have but little tendency to

improve savage nations. The Hottentots in Southern Africa, and the

natives of America, have not acquired civilization from the European

nations that have been planted beside them. The Hindoos, though

much farther advanced in civilization than these barbarous nations,

are not advanced so far as to be susceptible o f imbibing further improvements

; and, accordingly, they have reaped no benefit from the

example of the various civilized nations who have been repeatedly

planted among them. The same remark applies to the Chinese.

Religion seems, in some cases, to constitute a barrier against all

further progress in civilization. Hence, probably, the reason why

the inhabitants of India and China have stopped short at that half-

2 L